While it is supporting R&I activities and addressing the brain drain, the Teaming instrument can be unpredictable and complex

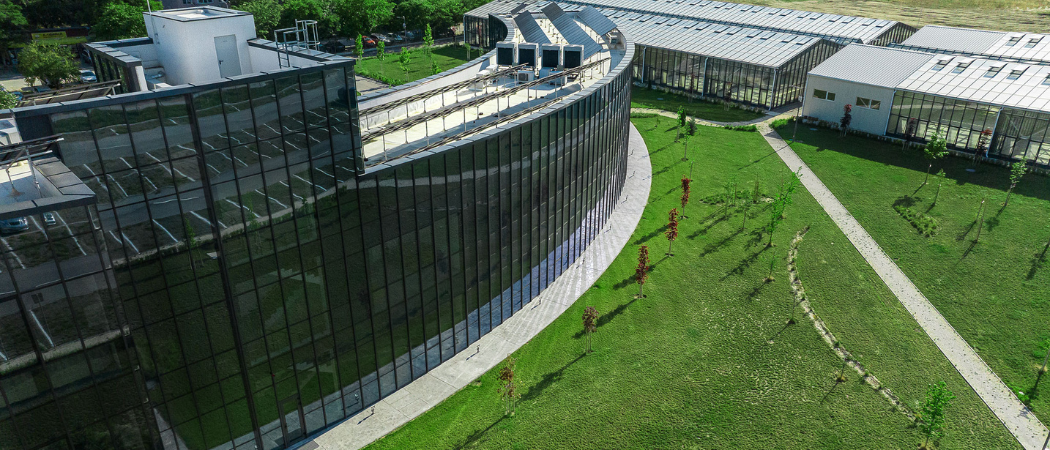

The Center of Plant Systems Biology and Biotechnology (CPSBB) was established in Plovdiv, Bulgaria, in 2015 with the help of the Horizon 2020 Teaming project, PlantaSYST. Photo: CPSBB

Teaming for Excellence, which is designed to support the creation or upgrading of centres of excellence in Widening countries with underperforming research systems, is showing signs of success in addressing brain drain and stimulating national funding of research.

But ambiguities in the provision of national funding and complex local administrative procedures are posing challenges for early participants.

At the same time there is concern over whether centres will get enough support to become self-sustaining in the long-run.

Under Teaming for Excellence, centres established in a partnership of at least two institutions can get from €8 million to €15 million from Horizon Europe. At least one of the partners must be in a Widening country, and while non-widening partners do not get funding, they benefit from networking and knowledge exchange.

To get Horizon Europe money, Teaming projects must have matched funding from national or regional programmes, from other EU funds such as the Cohesion programme, or from private sources.

One of the major benefits for Widening countries is the stimulus this generates for institutional and systemic reforms and the promotion of research investment at a national level. However, participants say raising the matched funding is a challenge because of complex and lengthy procedures and a lack of clarity about funding allocation.

Veselin Petrov, a scientist and head of the funding department at Centre of Plant Systems Biology and Biotechnology in Bulgaria, said initially it was unclear how national funds would be provided, resulting in delays. Other issues, including a lack of clarity about administrative procedures have since been resolved.

Participants in Slovakia also stressed the importance of the matched funding, which typically covers infrastructure and equipment costs, arriving in time.

Kvetoslava Papanová, coordinator of national contact points for Horizon Europe at the Slovak Centre of Scientific and Technical Information told Science|Business that the timing of Teaming calls should accommodate potential delays in approving Smart specialisation strategies outlining key research priorities; the possible delays in approving national operational programmes; and the complex process of getting matched funding from national agencies. “This has to be taken into consideration when the European Commission plans the publication of [Teaming] the calls in the next programming period,” she said.

Anna Voseckova, national contact point for innovation & technology at Technology Centre Prague, agreed that the biggest challenge is that as a synergy grant, Teaming requires applicants to find other funding sources. On a positive note, the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports in Czechia reacted quickly and flexed its rules to be able to co-fund Teaming projects.

Bureaucratic barriers

To improve Teaming for Excellence, participants want to see greater support from national agencies and the removal of bureaucratic barriers.

“Bureaucracy affects personnel hiring, wage flexibility, acquisition of research materials, consumables and equipment, recognition of the diplomas of foreign scientists, [and] participation of Teaming researchers in research projects funded through alternative mechanisms,” said Helena Mendes, deputy administrator at Universidade de Coimbra, Portugal.

To circumvent this, she proposes there should be pre-negotiation of the funding scheme between the Commission and national governments, to address barriers that are slowing down implementation of these projects. Teaming projects should have protocols exempting them from the bureaucracy of host universities, which is incompatible with competitive research, Mendes said.

Petrov also called for clear mechanisms for getting matched funding from national authorities and for advance planning for the long-term support of the centres. In addition, he pointed to the need to monitor less obvious obstacles, such as the rising cost of materials increasing the cost of building new research centres. Petrov suggested regular monitoring of construction and labour and updating of projects in the case of drastic cost over-runs.

Another key challenge for Teaming Centres of Excellence is attracting high level researchers. As Mendes noted, low salaries in Widening countries can make it difficult to attract talent. And alongside the practitioners, the centre need experienced management teams to run them in line with the best international practices.

Ten years later

Almost a decade after the Teaming initiative was launched, there are 39 ongoing projects, with 12 more expected to be selected later this month. The appetite to set up new centers remains strong. However, some Widening countries, for example, Romania have not established any yet, citing lack of predictable funding and insufficient support from national contact points.

At the same time, participants question whether having too many centres of excellence will affect their performance in the long-run.

For Petrov, setting up too many new centres could dilute their efficiency and potentially hinder long-term development, due to competition for limited financial and/or human resources. To avoid this, he proposed setting a threshold for the number of Centres of Excellence in any given area, based on per capita or a similar metric.

In contrast, Voseckova is in favour of more, smaller centres, funded by reducing the EU contribution to €7 million - €10 million per project. “I am sure we need more Teaming centres, but smaller in size to cover efficiently and effectively new research and innovation challenges,” she said. Teaming projects should be seen as “lighthouses in the Widening countries,” she added.

Papanová suggested there should be a case-by-case approach for deciding whether to establish new centres. She also stressed the importance of networking and cooperation between centres, proposing the establishment of a platform for participants to facilitate sharing of infrastructures, knowledge and human capital.

At an EU level, the Teaming initiative is complemented by the Excellence hubs, which focus on networking and policy development. While Teaming relies on collaboration between Widening and non-widening partners, Excellence hubs are based around the cooperation of at least two Widening ecosystems, with the aim of strengthening international cooperation among academia, businesses, governments, and society.

Excellence hubs place a stronger emphasis on applied research and contributing to the formation of spin-off companies and supporting small and medium-sized enterprises. “Excellence hubs complement Teaming very well and can be regarded as a very appropriate secondary tool to contribute to the sustainability of Centres of Excellence established by Teaming projects,” Petrov said.

The Teaming objective is to make the centres self-sustainable in six years, but without private investment stakeholders feel this is overly optimistic. However, Papanová said the centres of excellence status is giving them a competitive advantage in building cooperation with private companies and has opened up opportunities for exploiting the innovation potential of research projects.

But the ability to attract industrial partners varies depending on the sector, and while interest is generally high in fields like biomedicine, securing private investment in social sciences can be challenging.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.