Criteria proposed by Commission for awarding funds and defining “transition” countries risk punishing lagging states

European Innovation Scoreboard report published on July 15

The European Commission’s plans to establish new funding criteria for Widening countries based on their R&D spending risk being seen as “a punishment,” observers say. As a result, they may prevent systemic progress.

Until now, the Commission has tracked progress among Widening nations through the EU Innovation Scoreboard. But from 2030, nations that have not increased their public R&D expenditure in the year prior to the assessment will not be eligible for capacity-building support through the Widening programme.

According to Ricardo Migueis, Brussels representative for the INESC, Portugal’s largest research and technology organisation, this new assessment method “overlooks the fiscal constraints and developmental trajectories of many Widening countries, and fails to account for broader cohesion objectives.”

Instead, the transition beyond capacity-building should be framed “as a progression, not a punishment,” he told Science|Business.

“After investing in research and technology infrastructures and skills, it’s legitimate to expect national and regional systems to mature,” he went on. “However, using the Framework Programme eligibility as leverage to compel increased national own-resources research and development expenditure risks being unfair.”

Incentives

For Monica Dietl, director of Europe Matters and, like Migueis, a participant in the European Parliament’s informal Widening task force, the Commission is not seeking to penalise or favour some countries, but to incentivise them. “The question is if it is the right way to do it,” she said.

Related articles

- Horizon Europe budget to double, but €68B will remain in Competitiveness Fund

- Commission draft proposal for FP10 leaked

Migueis believes that performance-based incentives should be transparent and stable, and “avoid distorting national and regional strategies, reinforcing disparities, or worse, encouraging an ‘indicator-as-goal’ mindset.” In his view, the Commission should recognise effort and trajectory rather than speak in absolute figures.

It could also require a larger share of structural funds to be invested in research and innovation, provided that the process is tailored to support both emerging and more advanced research and innovation performing nations.

CEITEC Masaryk University has also called for better alignment of FP10 with national and structural funds in a bid to improve the effectiveness of public investments. This would be “a more balanced approach,” it said in a statement released on July 22.

Inclusivity

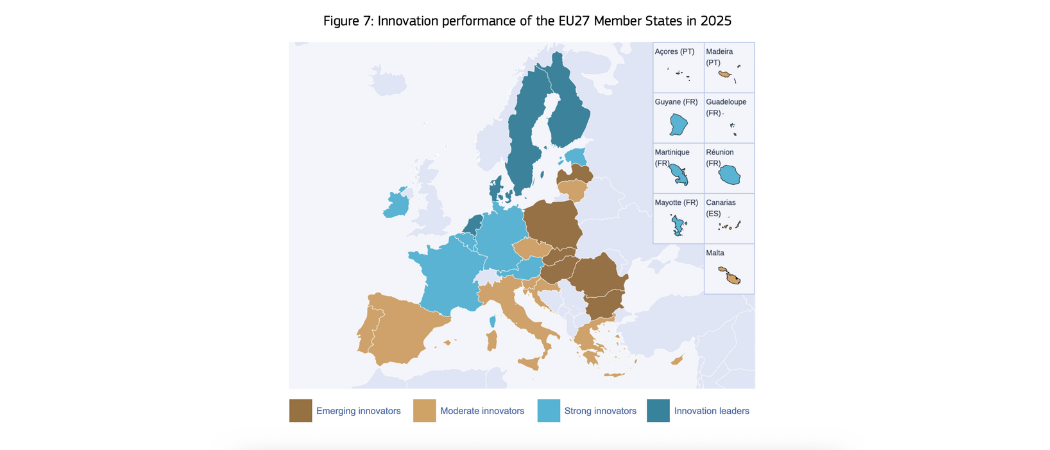

For funding purposes, the Commission also intends to split eligible countries into two categories: regular Widening countries and transition countries, defined as member states with an innovation scoreboard index above 75 that have increased their participation in Horizon Europe. The transition countries are currently Cyprus, Estonia, Greece, Malta, Portugal and Slovenia. This leaves Croatia, Czechia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania and Slovakia as regular Widening countries.

Dietl thinks that this distinction goes against the Commission’s desire for simplification and warned against determining such division on just two criteria. Besides, “even if some of [the Widening countries] have been doing better, it’s better that we stick together,” she added.

Migueis agreed. “FP10 must preserve a vision of excellence with inclusion, not excellence against inclusion,” he said.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.