As 2024 begins, we assess the success of attempts to close the EU’s east-west research and innovation gap. There is progress, but a decade on, disparity persists and alongside beefed up EU measures, national R&D funding needs to increase

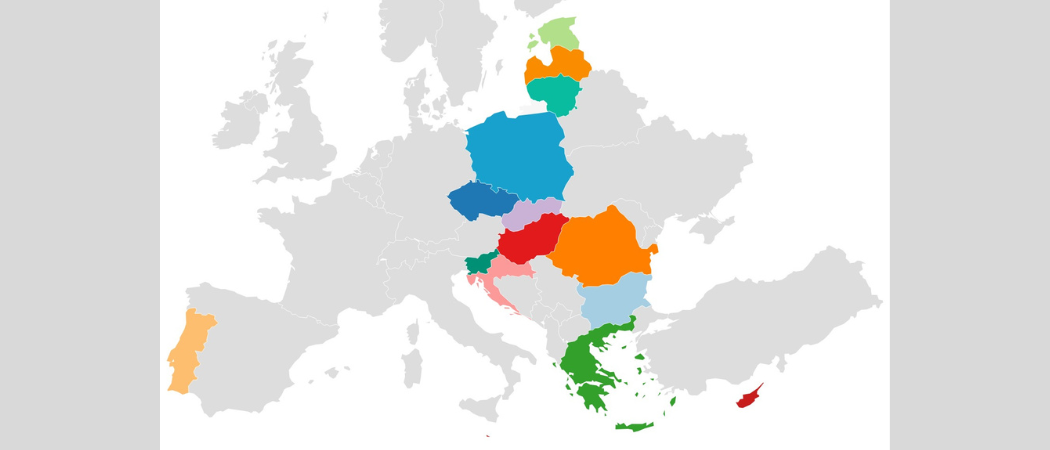

The 15 EU Widening countries under Horizon Europe

This year marks a decade since the Widening participation and spreading excellence programme was first introduced to Horizon 2020 with the goal of improving the research and innovation ecosystems in the framework programme’s low-performing countries.

‘Widening measures’ were initially given a budget of just under €1 billion to help eligible countries network with leading research institutions, learn from top scientists, gain experience in call applications and running projects and attract and retain skilled staff. Essentially, for them to get more out of the framework programme and to close the research and innovation gap.

Widening was expanded when Horizon Europe began in 2021, with research ministers agreeing to ring fence 3.3% of the €95.5 billion Horizon Europe budget – just under €3 billion – for these measures. This was seen as a big victory for MEPs and countries behind a long-running push for a more level playing field in the EU’s research programme.

Boštjan Šinkovec, senior EU affairs advisor at the Slovenian Business & Research Association, told Science|Business he thinks that to date Widening measures have only partially fulfilled expectations.

“The surprising mistake was that the measures were introduced only when it became obvious that [Widening countries] couldn’t compete on an equal footing,” he said. “That was recognised with some delay, and initially wasn't very effective.”

However, Šinkovec acknowledges Widening measures have eventually had a positive impact. “Not saying that it couldn't be better, but it has to be admitted that Widening measures have helped Slovenian researchers to be rather successful in EU research programmes,” he said.

Widening measures should continued and even enhanced further to reduce the economic differences between member states and help them better integrate, Šinkovec said. “European advanced societies should not ignore this important premise of integration.”

Lenka Procházková, head of office at the Czech Liaison Office for Education and Research in Brussels, is also supportive of Widening measures and thinks that they have helped to “jump-start progress” in Czechia.

“Projects funded under the widening measures have provided our institutions with invaluable experience in EU cooperation, subsequently encouraging stronger internationalisation of our research institutions,” she said.

But moving forward, she admits that the measures need to be developed to match the evolution of Europe’s R&I environment, and calls for a shift towards “empowering and fostering excellence”, rather than merely “supporting participation”.

“In order to create a well-balanced European Research Area we need to continue in this endeavour, focus on critical elements, adjust the widening measures to the current needs and aim at more balanced participation of the widening countries in all parts of the framework programme,” she said.

But wider scepticism of the measures remains and ten years on the data show progress in certain areas, but stagnation in others. While Widening countries as a whole have massively increased their participation in Horizon projects and have won an increasing amount of money, the gap between the bottom- and top-performing countries remains.

There are currently 15 Widening countries: Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia. Luxembourg was considered a Widening country under Horizon 2020 but not for Horizon Europe.

Top performers

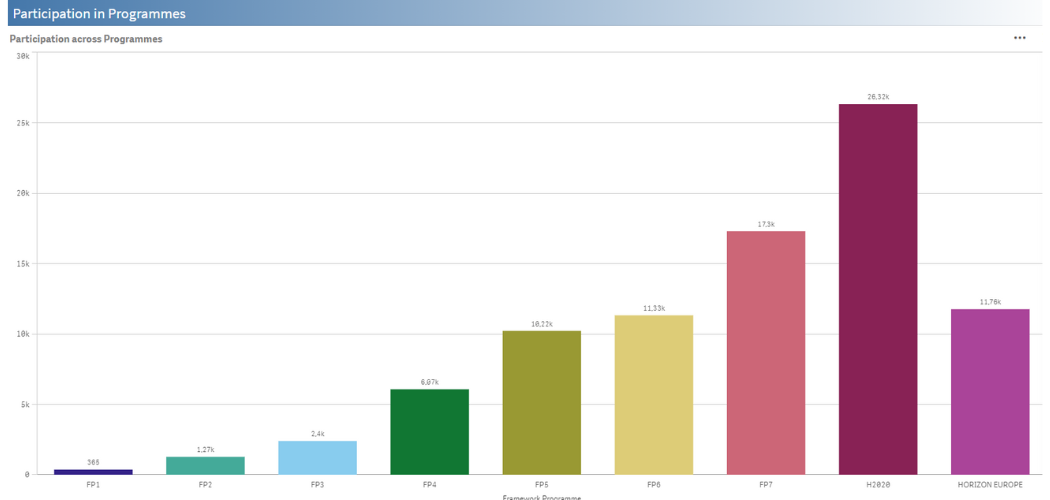

Between Framework Programme 7 in 2007 - 2013 and Horizon 2020 in 2014 - 2020 there was a notable jump in the number of projects that researchers and institutions from Widening countries participated in, as shown in the graph below.

(FP7 was the first framework programme to run for seven years; the previous programmes lasted four years and the first, FP1, ran for three years).

The majority of the current 15 Widening countries joined the EU in 2004, with Romania and Bulgaria joining three years later in 2007 and Croatia in 2013, meaning Horizon 2020 was the first framework programme where all 15 countries were involved as EU members.

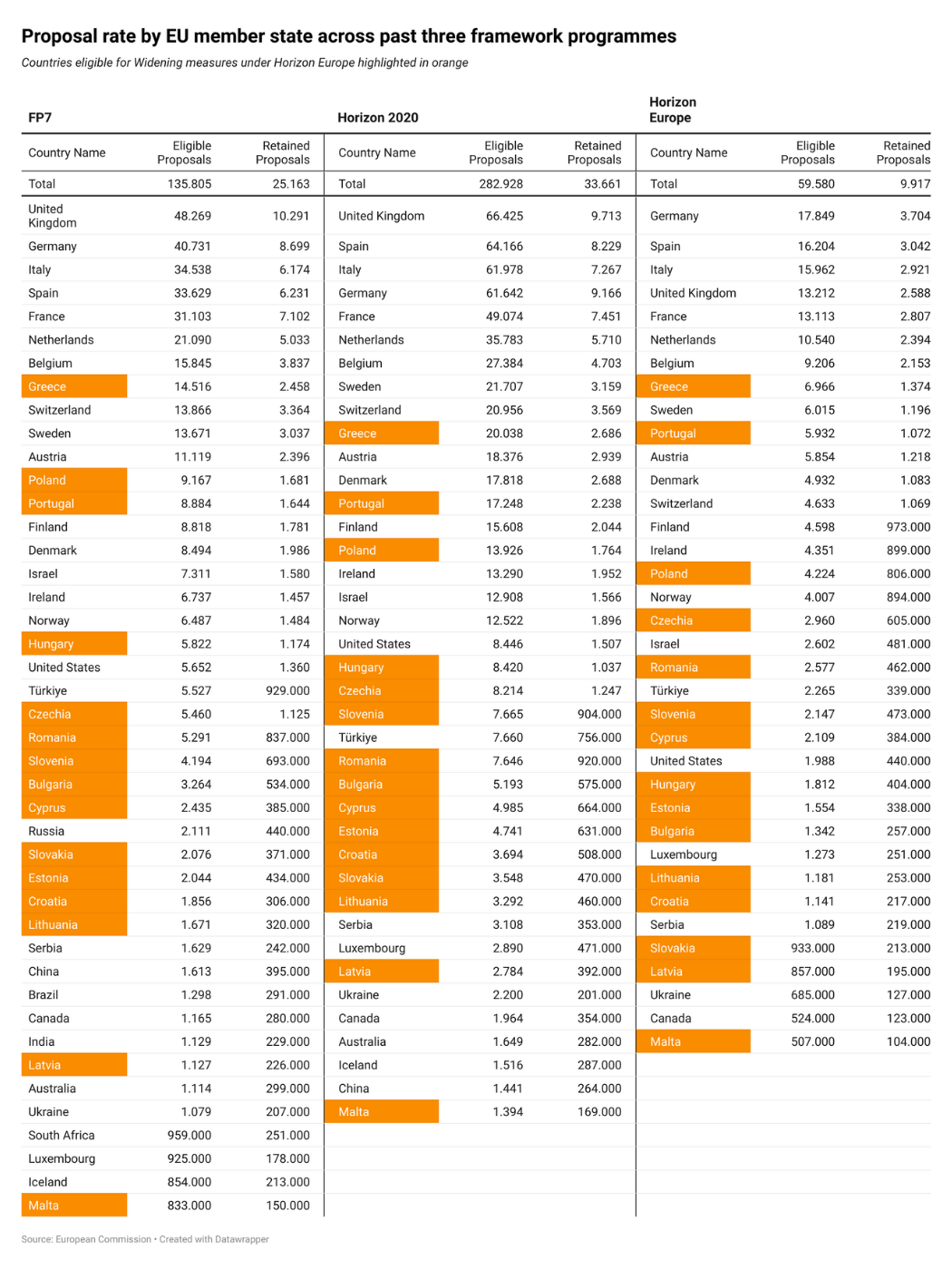

Another way to look at participation levels is by assessing the Widening countries’ performance compared to other EU member states. In this respect, not much has changed between FP7 and Horizon Europe.

The older EU member states such as Germany, France, Spain, Italy, the Netherlands and Belgium continue to dominate the number of grants given out overall. Currently, almost half-way into Horizon Europe, the only Widening countries performing better than non-Widening EU countries in the number of proposals they have had funded are Greece and Portugal, as shown in the table below.

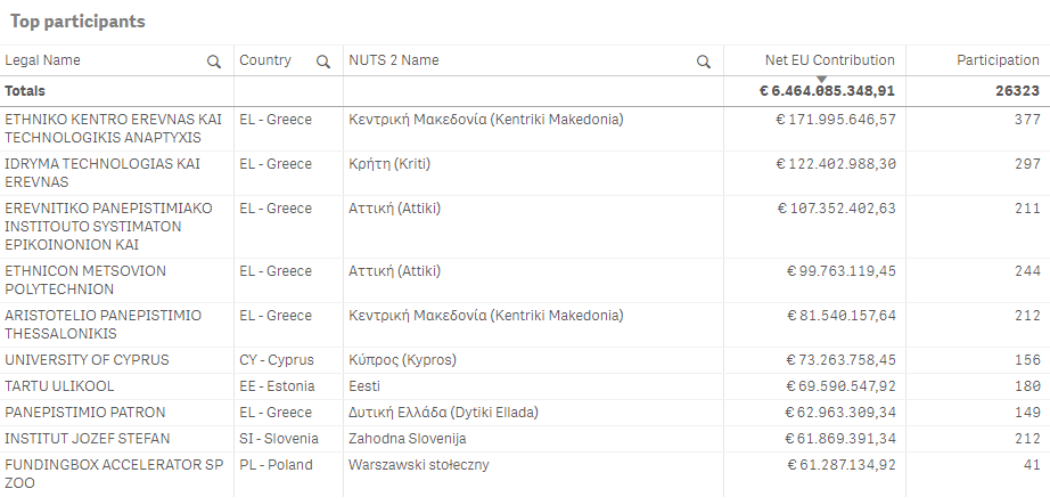

These two countries are by far and away the best performing Widening countries, with Greek institutions dominating the list of those winning money from Horizon Europe in the Widening countries.

As the table shows, Widening countries continue to perform worse than non-Widening EU countries in winning grants through the framework programme. Poland, for example, submitted and won more proposals than Finland, Denmark and Ireland under FP7, but today lags behind all three.

The table below shows the success of Greek institutions in winning Horizon 2020 funding compared to other Widening countries.

National support

A comprehensive review of Widening measures has yet to be carried out by the EU, but more information on their effectiveness should be included in the evaluation of Horizon 2020 scheduled for publication later this month.

One evaluation that is available was carried out by the European Court of Auditors in 2022, which said that while the measures are well designed, national measures are the key to sustainable change. “Genuine sustainable change is dependent on national governments fully playing their part in making R&I a priority, both in terms of investment and reforms,” the report says.

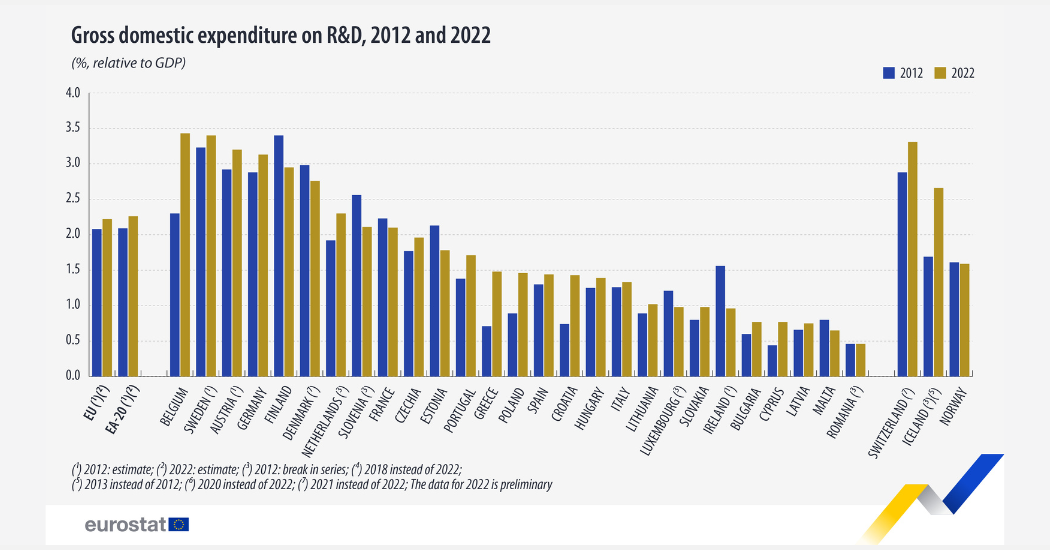

The majority of Widening countries have increased the proportion of the state budget that they dedicate to R&D. The EU as a whole has set the goal of reaching the 3% mark but remains some way off that.

While most Widening countries have increased their R&D intensity over the past decade, they still mainly lag, as shown in the graph below. For there to be any realistic chance of Widening countries improving their research performance, they will need to significantly increase domestic funding of R&D.

There is also a disparity between basic and applied research with the proportion of researchers from Widening countries winning grants from the European Research Council increasing from 3.66% of the total in Horizon 2020, to 5.65% under Horizon Europe, a small but notable improvement.

On the other hand, the latest EU Regional Competitiveness Index published last year and taking into account 2022 data, shows that all eastern regions, with the exception of most capital cities, are below the EU average in competitiveness. So-called ‘catching-up’ regions in Czechia, Slovakia, Romania and parts of Bulgaria, are actually moving further away from the EU average and getting less competitive.

Only Estonia, Lithuania and Slovenia score about the EU average in the index, with Czechia falling just below.

The index has been published every three years since 2010, but comparisons are difficult to make because of different methodologies used to measure competitiveness. The latest report, was branded ‘Index 2.0’ to reflect modifications in the methodology.

What is clear looking at each of the reports is that there is a consistent gap in competitiveness between north and western European states and south and east European states.

The generally lower competitiveness of Widening countries is reflected in the region's performance in winning European Innovation Council (EIC) grants for start-ups and SMEs.

The EIC is aware of this and has set a target of doubling the participation rate across its three programmes to 15%. To date, the success rate for the 15 EU Widening countries is 10.8%.

Countries such as Germany, France and Spain all individually have a higher participation rate in EIC programmes than all 15 Widening countries combined.

In July last year EIC set out six recommendations to increase participation in its programmes from Widening countries. These include greater information sharing, training, better identification of high potential companies in Widening countries and increasing the ratio of EIC jury members from Widening countries from below 20% to at least 30%.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.