The country has announced further alternatives for its researchers, and wants to bolster its quantum and space sectors

Switzerland has announced a slew of new research funding initiatives, designed in large part to compensate for its continued exclusion from the EU’s Horizon Europe framework programme.

As well as replicating the Horizon calls from which it is excluded, the country has said it wants to strike more research deals with countries outside the EU and to bolster its research prowess in quantum and space research.

Due to a broader diplomatic stalemate over Bern’s wider relationship with Brussels, Switzerland is not currently associated to Horizon Europe, meaning its researchers cannot apply to individual grants like those from the European Research Council, and must find their own money to join consortia.

“I’m aware that the current situation for researchers and innovators in Switzerland is challenging,” admitted education, research and innovation state secretary Martina Hirayama in a press conference on 5 May announcing the measures.

Switzerland has already said it will stump up money for researchers to participate in consortia, and created its own equivalent versions of ERC and other grants.

On 4 May, the country’s Federal Council announced another tranche of money for these measures, funding Swiss researchers to join the 2022 Horizon calls that are still accessible to them and native replacement grants.

Last year, the Swiss government set aside the equivalent of €543 million to cover these alternatives. This year, that will hit €639 million.

In addition, the Swiss government announced a series of additional pots of money to fund priorities that Hirayama said would go ahead regardless of Horizon association status.

The first is the equivalent of around €14 million to help cut new global research deals with other countries. She said that Switzerland wanted to “diversify” its international partnerships and “minimise” dependence on any one particular partner. Part of its strategy, agreed by the Federal Council yesterday, is to agree new partnerships both in and outside Europe, “for example with the USA, Israel or Japan”, she said.

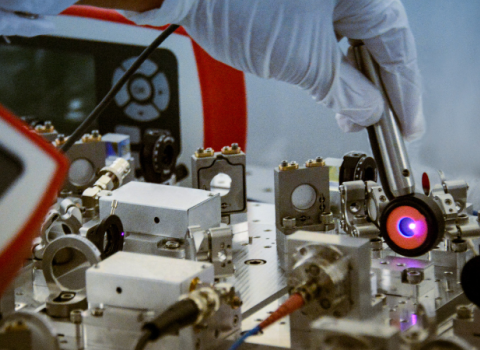

The second is a €10 million grant in 2023-4 for a new national quantum initiative, a field in which Switzerland is particularly strong.

Switzerland is also looking to bolster its space capabilities too. Later this month, the country will ink a cooperation agreement with the European Space Agency to create a so-called European Space Deep-Tech Innovation Centre, based at the Paul Scherrer Institute, a natural sciences and engineering research centre located between Zurich and Basel.

Quantum and space have been areas where Switzerland risks being excluded from EU networks by a growing focus in Brussels on “strategic autonomy” over particularly sensitive technologies. Last year saw a row between the Commission and member states over whether to exclude neighbouring non-EU countries like the UK, Israel and Switzerland from quantum and space projects.

In the end, the UK was allowed to participate in both fields, and Israel in quantum.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.