Researchers stunned as draft Horizon Europe work programme shuts out close research partners. ‘This is not in Europe’s interest’ says leading quantum physicist

Klaus Ensslin, professor of solid-state physics at ETH Zurich. Photo: ETH Zurich/D-PHYS Heidi Hostettler.

Brussels is preparing to exclude researchers based in the UK, Israel and Switzerland from major quantum and space research projects, in a significant step that researchers and officials warn could have broad implications for science collaboration across Europe.

Read The Horizon PapersScience|Business is publishing here all the draft Horizon Europe work programmes available to us. You can read them here. Or, if you have additional ones, you can send them to [email protected] (anonymously, if you wish.) |

According to the latest draft plans for Horizon Europe, restrictions will be placed on the EU’s closest research partners in several quantum and space competitions. Until now, these projects were open to the association countries, which have negotiated access to EU research programmes.

The proposed move, which came from the European Commission and is now under discussion by member states, was greeted with dismay and sadness from researchers and officials, who said curbs would hurt all of Europe.

“Everyone’s shocked; we’ve never seen anything like this. This is not good for us, not good for the field, and not good for the EU,” said Klaus Ensslin, professor of solid-state physics at ETH Zurich.

The draft text argues that the move is necessary so the EU can protect its research base in rapidly developing fields. The language highlights just how much the EU’s thinking has shifted when it comes to striking the balance between research collaboration and competitive interests. The proposal would see fewer resources in key scientific areas go to associate countries, and more resources dedicated to developing these sectors at home.

“There have been certain indications that something like this had been building up. But this was quite dramatic,” said Nadav Katz, a quantum physicist who runs the Quantum Coherence Lab at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. “This is not in Europe’s interest,” he said.

Israel is one of over a dozen non-EU states that along with Switzerland and the UK, is expected to be formally involved as a fee-paying associate member of the seven-year Horizon Europe, which starts issuing grants in the coming months.

Katz, whose research focuses on superconducting devices for quantum computers, said there are up to 20 quantum projects running in Israel that involve EU partners and funding.

“The EU has been very wise to include neighbouring countries in its research programmes over the years. Pushing them away is not good policy. These are countries that give more than they take,” said Katz. “The European landscape will be greyer and dimmer without their participation.”

The proposed curbs would leave Switzerland and Israel with less privileged access to Horizon Europe than they have had in past R&D programmes. For the UK, too, which formally left the bloc at the end of last year, the move would see a big downgrade of its role in key EU projects.

Ending cooperation in key quantum and space research would also see the EU take a hit, as its universities and labs lose vital partners, researchers warned.

“Friends need to stick together; otherwise, you end up alone,” said Tal David, head of the Israel National Quantum Initiative.

The European Commission did not respond to a request for comment.

Nobody expected this

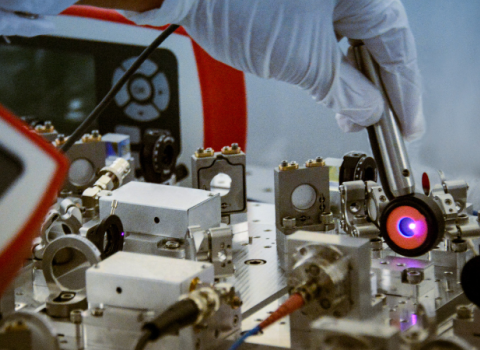

Researchers involved in the EU’s multi-billion Quantum Technologies Flagship, which is funded by Horizon 2020, were blindsided by the exclusions, which appeared for the first time in a draft that circulated last week.

“It was a big surprise,” said Tommaso Calarco, a theoretical physicist at the Helmholtz Centre in Jülich, Germany. Calarco is one of the leading forces behind the EU quantum programme that aims, among other objectives, to develop quantum computers that are exponentially more powerful than today’s supercomputers.

“Nobody expected this,” Calarco said. “It’s sad that things are working like this, because science is without borders.”

The three directly affected countries, Israel, Switzerland and the UK, carry considerable scientific heft, as demonstrated by how their researchers excel in highly competitive EU programmes, Calarco noted. They are also among the biggest investors in quantum research in Europe. “If [the plan] stays as it is, we need some serious contingency plans,” he said.

Officials from the EU’s big neighbouring players are fighting to ensure their researchers do not lose out, and are expected to raise their concerns with government representatives ahead of a key Horizon Europe meeting later this month.

Barring these countries “would be a particularly disappointing development,” said John Morton, director of University College London’s Quantum Science and Technology Institute.

The real battle is not between states but “against the laws of physics; in overcoming the significant scientific and technical challenges that will allow these technologies to achieve their enormous potential,” Morton said. Long term, researchers hope to apply quantum physics to build highly sensitive instruments and machines with calculation capacities far beyond those of the most powerful current supercomputers.

“It’s not clear how [barriers] serve the interest of the EU member states,” said Morton. “It is difficult to see how such measures can increase the expected return on investment to member states in capturing the value of emerging quantum technology. Indeed, it seems more likely to achieve the opposite.”

What the text says

The proposed new eligibility rules includes restrictions on who can join a project on, for example, quantum computers, described in the text as an “emerging technology of global strategic importance”.

“In order to achieve the expected outcomes, and safeguard the Union’s strategic assets, interests, autonomy, or security, namely, participation is limited to legal entities established in member states, Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein. Proposals including entities established in countries outside this scope will be ineligible,” the draft says.

In addition, the text says that legal entities established in a member state or in countries associated to Horizon Europe, such as Norway, “that are directly or indirectly controlled by third countries not associated to Horizon Europe or by legal entities of non-associated third countries, are not eligible to participate.”

The text defends these restrictions, saying the goal is to “make independent European capacities in developing and producing quantum computing technologies of strategic importance for future computing capacities and applications in security and dual-use technologies.”

Similar restrictions appear for other hot-button quantum topics, including simulation, communications, and sensing projects.

There are also strict limits proposed for non-EU participation in space projects, such as satellite communication and transportation systems and space launchers.

According to the text, “In order to…avoid EU dependence on components, materials, processes from non-EU countries and the risk of access restrictions for such items e.g. through export control regulations, participation is limited to legal entities established in member states only.”

A disclaimer on the front of the document states that the proposals are “the preliminary views of the Commission services and may not in any circumstances be regarded as stating an official position of the Commission.”

As a member country of the European Space Agency, it is “crazy” to talk about excluding Switzerland from space projects, said Olivier Küttel, head of international affairs at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne. “Scientifically speaking, none of this makes any sense. It’s a pity; the EU is growing more focused on itself, I feel. We are stuck in some politics that limits all our potential.”

Bad precedent

Officials in Brussels say there are several considerations behind the proposed exclusions, with the main one being that quantum and space are expected to become increasingly important elements of national security.

However, researchers fear these bans will set a bad precedent that may be used to justify further research barriers between the EU and its neighbours.

“Today, it’s quantum and space. Tomorrow you will be talking about artificial intelligence and who knows what else,” David said.

Calarco is calling for member states to negotiate a deal that keeps associate countries in all quantum topics. “This is all happening above our heads and we don’t have much information on it. We understand it’s bigger than us, but I still would like to hope that this can be fixed,” he said.

Scientists said access to the quantum flagship is so important that any partial exclusion for Israel, Switzerland and the UK would see the EU as a whole drop out of the top tier of quantum research. The programme, which launched in 2018, will provide funding for the next 10 years. The project has distributed €150 million in grants so far, with over €1 billion still to spend over the next seven years.

“This is potentially a major blow to quantum research in Switzerland, but also to UK and Israeli researchers,” said Ensslin.

“Actually, I would say that it is a blow also to European quantum research since exactly these three countries are particularly strong in quantum. If [the EU] were to kick these groups out, the European quantum effort would become severely weaker.”

A joint statement by Ian Walmsley, provost and chair of experimental physics at Imperial College London, and Kai Bongs, professor of physics and astronomy at Birmingham University, underlined the importance of continued access for the UK.

“As part of the EU, the networks and collaborations that UK researchers and companies established, as well as the training programmes and the exchange of people, have been crucial in growing the national and European capabilities in this area. It would be a pity to discard the strengths that these have provided both sets of nations,” they said.

Bongs is principal investigator at the UK Quantum Technology Hub for Sensors and Timing, overseeing the development of gravity sensors or gravimeters that are predicted to be twice as sensitive and 10 times as fast as current equipment. Speaking to Science|Business last month, he shared his fear that, “Europe is not quite as open to the UK as it used to be.”

Now, he and Walmsley say whatever the outcome on Horizon Europe, they expect global companies would “continue to collaborate both with us and our EU colleagues.” It would therefore be at best inefficient to erect a barrier for direct collaboration between researchers, while having them each collaborate with the same industry partners, they added.

“A critical mass of activity is needed to make progress, and Europe has this. Fragmenting the strong connections we have scientifically with the EU would be detrimental to both UK and the EU research and innovation in the face of very stiff international competition,” Bongs and Walmsley said.

Strategic autonomy

If some member state officials were taken aback by the strict proposals, others said that the political mood had been threatening a move like this for some time.

Even before the pandemic added new elements of uncertainty and massive spending deficits, the main political message heard for several years is that the EU has to fend more for itself.

In particular, since Donald Trump entered office with his hostility for the EU, leaders like French President Emmanuel Macron have been pushing for what he has called European “strategic autonomy,” the ability to defend Europe and act militarily in its neighbourhood without so much reliance on others.

To this end, quantum applications are viewed in Brussels as huge economic and military opportunities but also as significant threats, not least to critical EU assets like the Galileo and Copernicus satellite systems which may one day have to stand up to quantum-based attacks.

“I’m not really surprised [by the proposed exclusion] from a political point of view,” said Tilman Esslinger, a German experimental physicist and a professor at the Institute for Quantum Electronics at ETH Zurich. “Clearly quantum has gained geopolitical importance. It’s today’s moon landing. If you can master it, you demonstrate to the world that you can master any technology.”

Last year, the EU’s director general for research, Jean-Eric Paquet, said the EU would be more selective about research partners for Horizon Europe. “The DNA of [the Horizon programme] does not change. Cooperation in science is a no-brainer for us. At the same time, the world is deeply changing and we need to revisit the way this is done in practice,” he said.

The EU will become more “specific, nuanced” on how “we open our programmes to the world,” Paquet said.

Following these remarks, EU research ministers agreed to more aggressively police foreign participation in the science programme, adding a new provision analysts say was aimed primarily at preventing China and the US from getting access to sensitive European research.

Toughened legislation allows Brussels to limit or block a far wider array of entities from participating in Horizon Europe, as Europe tries to prevent rivals from gaining an edge in industries projected to power the economy of the future. The EU promised to exercise this power for “duly justified and exceptional reasons.”

Still, it has come as a shock to see how broadly the Commission may be willing to apply its new authority.

One interpretation, shared anonymously by a non-EU official, is that the trauma of Brexit has created a great power game between the EU and UK, with collateral damage for Israel, Switzerland and other non-EU countries.

Whatever lies behind the EU restrictions, the signals from Brussels have changed in recent years, said David. “Our influence on decision making in Europe has always been limited, which is to be expected, we’re not a member state. But in the past year or so, it has become [even] more limited I feel,” he said.

Quantum research is becoming more difficult to collaborate on around the world, David added. The US is talking about export controls for the technology, for fear it may be helpful to other countries’ military or commercial companies; there are similar noises in China about stopping its quantum knowhow going overseas.

Israel recently unveiled plans to increase its funding for the field, with a €300 million programme running to 2025. David says the country is not thinking about putting barriers around this funding. “Europeans are coming to us, interested to get funding from our programme,” he said.

He called research collaboration a “tremendous” mutual benefit for Israel and the EU. “This connection is very important to maintain because the [quantum] community is small enough, and the challenges are significant enough, that you cannot really do it without collaboration,” he said.

The large majority of joint work on quantum remains in early stage research, which is not classified or categorised as a deemed export. “We’re closer to basic science than field-ready projects, so there’s no reason, really, to limit collaboration now,” David said.

He thinks some officials may be “blinded by the hype” of the field. “There’s great promise but it’s too soon to be talking about science fiction-grade security threats,” he said. “Many quantum projects are not security-related, anyway. Quantum sensing, for example, there’s a lot of civilian applications here.” These include sensors to measure volcano activity, and tools to detect degenerative diseases.

Katz said there is no risk of intellectual secrets escaping, if this was something worrying officials in Brussels. “We’re law abiding countries, if there’s IP [intellectual property] protection, we abide by it,” he said.

“It’s overall a really good personal connection we have with EU partners. We definitely see ourselves as part of the community. But ultimately, if we don’t work with Europe, we will work with someone else,” he added.

Excluding Europeans

If EU officials are worried about losing researchers to the UK or to Switzerland, the answer is to increase national funding across the bloc, said Esslinger.

“Researchers would love to study in all these great EU countries but often times, the positions aren’t available. That’s why a lot of people went to Britain originally to do quantum,” he said.

Talent cultivated in the EU’s neighbour states ultimately bolsters the bloc’s economy anyway, Esslinger said. “Probably the leading course on quantum engineering in the world is here, at ETH. We train PhDs, some stay, and many leave back to their home countries. That is to the benefit of Europe.”

“If the EU goes through with these restrictions, they will be excluding many Europeans. I’m from Germany. We are all international researchers,” said Esslinger. “So I am, frankly speaking, sad for European research, which had been so successful in quantum in the last 20 years.”

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.