More investment will ensure Europe takes a share of the future space economy, Josef Aschbacher, told MEPs. The ambition is to see ‘European astronauts, on a European capsule, on a European rocket’

European Space Agency director general Josef Aschbacher. Photo: Alexis Haulot / European Union

With “a double-digit percentage” increase in its budget, the European Space Agency (ESA) could put an astronaut on the moon within a decade, according to the agency’s director general, Josef Aschbacher.

ESA’s budget is currently around €7 billion per year, with two thirds coming directly from member states. “With a fraction more than that, we could engage significantly in exploration, even to the point where we could develop a mission to the moon,” he said. “We have the expertise.”

Aschbacher was speaking at a time when ESA is compromised by lack of independent access to space, as a result of delays to the next Ariane launch vehicle and with the war in Ukraine cutting off access to Russia’s Soyuz rockets.

China aims to land on the moon by 2030, India by 2040. Europe can get there between the two, if there is the funding and a clear mandate to do so, Aschbacher told the European Parliament’s industry, research and energy committee ITRE.

European astronauts are expected to walk on the moon for the first time later this decade as part of the Artemis 4 and Artemis 5 missions, which are a collaboration between ESA and NASA. But there is a growing wish for more European autonomy, and Aschbacher wants to see “European astronauts on a European capsule, on a European rocket”.

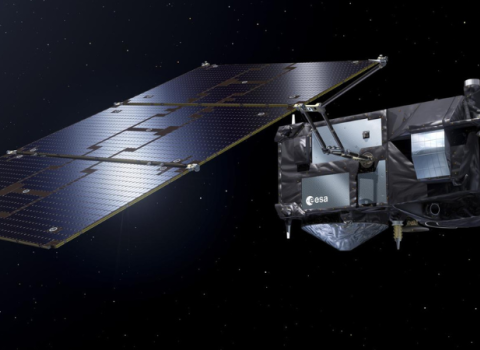

There is a lot of work to do before that becomes a realistic possibility. While he cited the Galileo navigation satellite system and the Copernicus earth observation system as major success stories, he said Europe must be more ambitious when it comes to exploration.

Today, the US, Russia and China are the three countries capable of launching astronauts into space, with India set to join them. “I am asking why Europe, such a capable continent in terms of engineering and excellence, is not able to do that,” Aschbacher said.

Eventually, Aschbacher wants to see European rockets with European commanders, also capable of carrying astronauts from Latin America, Africa, or even the US.

“This would geopolitically be a strong signal Europe is capable of mastering this technology, but also of engaging other countries in a cooperative project, just like is done today by the US, or China,” he said, arguing for the continent to use space as a form of diplomacy.

“Ten years ago, we were flying our astronauts with Russia. Can you imagine that being possible today? Now we fly them with America, which works very well, but we need more strategic autonomy. Not for the sake of doing it all alone, but being a strong partner.”

Wake up call

The last couple of years have been something of a wakeup call for ESA, with the loss of access to Russia’s Soyuz rockets, and delays to the Ariane 6 rocket, which was due to be operational in 2020. With Ariane 5 having been retired in July this year, Europe no longer has guaranteed access to space.

Last week, the Wall Street Journal reported that Elon Musk’s SpaceX has signed a deal to launch up to four European Galileo satellites. While the European Commission and member states must still give their final approval, the deal shows how dependent Europe is on other parts of the world.

Aschbacher admitted Europe is in a crisis when it comes to launchers, adding, “We have done serious analysis of the lessons learned”. He expects “important decisions” to come out of ESA’s Space Summit on 6 and 7 November, which will see ministers from the agency’s member states come together in Seville.

A 2024 launch date for Ariane 6 is expected to be announced after the next major test, which should take place at the end of November. Aschbacher said tests so far had gone better than expected.

Economic opportunities

The implications of autonomy are not just strategic, however. They are also economic. “Today, the space economy is worth roughly €460 billion. It is expected to grow to €1 trillion in the next decade,” Aschbacher said. “Europe has to be part of this.”

Space technology is expected to play an increasingly important role in numerous industries, from agriculture to pharmaceuticals.

ESA is even studying the feasibility of capturing solar power in space and directing it to earth, with its SOLARIS initiative. “If it works, it could liberate us from our dependence on energy from outside of Europe to a good extent,” said Aschbacher.

Aschbacher expects the first developments of housing infrastructure on the moon to take place in the next decade, and said the “moon economy” will be central to competition in the future, while many believe that rare earth metals could be found there. If Europe does not want to be left behind, serious investment is needed.

“NASA’s budget is about four times ESA’s budget. An increase by a good fraction would be a significant step to build up this capacity. If we don’t do it, we’ll miss the train, and the same will happen as happened in chips, or in IT,” Aschbacher said.

More ambition is also required in order to retain the best talent in Europe, he added. At the root of many of these problems is the fact that, in Aschbacher’s view, space activity is undervalued.

“Space is so essential for the daily life of every citizen, including for security, and climate change, that it has to be recognised. That means the budgets have to be adequately supported.”

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.