The race is on to be the first to launch a satellite from a base in Europe, but private space start-ups are finding it hard to get the investment they need for lift off - and to build a competitive EU sector

Benoît Deper, founder of Belgian satellite manufacturer Aerospacelab (left), alongside Raúl Verdú, co-founder of PLD Space at a deep-tech workshop organised by the Spanish Presidency of the EU Council. Photo: PLD Space / LinkedIn

Europe must support its private space industry to preserve its access to space following an end of access to the Russian launch site after the invasion of Ukraine and delays to the new Ariane 6 rocket at European spaceport in French Guiana.

The result is, “a deep crisis in terms of launch opportunities”, said Raúl Verdú, co-founder of PLD Space, which is hoping to launch its suborbital MIURA 1, Europe’s first private rocket, in October. This is a demonstrator for a second rocket, the orbital MIURA 5, which is scheduled for launch in 2025 from French Guiana.

With only 30% of its funding coming from public sources, PLD has been heavily dependent on private capital, but Verdú told a workshop organised by the Spanish Presidency of the EU Council earlier this month, convincing investors was one of the most difficult challenges.

That is despite MIURA 5, which will launch satellites of less than 500kg, having over €300 million in preorders, with the first two years of manifest full.

Customers include the European Commission, the European Space Agency (ESA) and national and regional governments.

The parachute system for soft landing MIURA 5 was developed as part of a contract with ESA. “They will have the IP and share it with us,” Verdú told Science|Business. “This gives us a track record with customers and the main stakeholders in the industry to develop our credibility.”

The Commission should act as an early adopter to show investors that the market exists. “We don’t need help, we need contracts,” Verdú said.

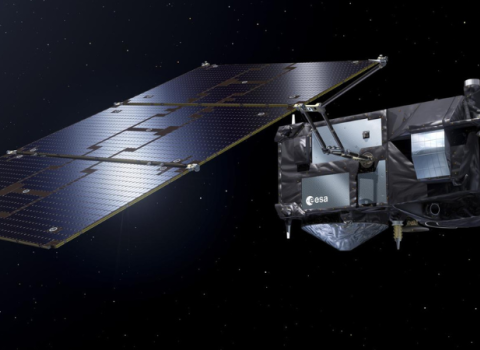

In March, ESA and the Commission launched the European Flight Ticket Initiative, for new satellites ready to be tested in orbit and for new launch service providers to launch them, with the initiative co-funding the flight tickets.

This is an important step forward, but Verdú would like to see it ramped up. “The opportunity for Europe today is massive, because there are so many promising companies.” Without support for private space start-ups, Europe will find itself reliant on US, Chinese or Indian rockets.

The constraints on Europe’s access to space comes at a time when there is an exponential increase in the number of satellite launches globally. Once development is complete, Ariane 6 will continue to guarantee access to space, but private companies are needed to fill this capacity gap, and to promote innovation. Reusable rockets for example promise to reduce launch costs.

“We are looking forward to having innovative solutions that can maybe benefit even more than just one of these individual systems,” said Thilo Kranz, programme manager for Boost!, ESA’s commercial space transport programme. “There is an ongoing discussion around how much of our business could be given to these new providers.”

‘Satellite wars’

Benoît Deper, founder of Belgian satellite manufacturer Aerospacelab, took an even dimmer view of Europe’s standing. “We failed the war on digital, and we are likely to fail this infrastructure war as well,” he said. “The money is there, but the governance is so complex. It’s tough to come up with actionable plans that are agreed upon by everyone.”

The mass-production of satellites, which Deper referred to as a “Henry Ford moment” provides an opportunity to make up ground. Aerospacelab is currently building the third largest satellite factory in the world in Charleroi, where it aims to make 500 satellites each year.

Europe’s private space industry is clearly lagging behind the US, according to Francesco Nicoli, visiting fellow at the Bruegel think tank, who is the co-author a recent paper analysing Europe’s space launch industry.

“Every other country in history together has launched far fewer satellites than SpaceX alone in the past couple of years,” he said.

It is not simply a question of how much public money is invested, but also of how it is invested, Nicoli said. “Ariane was great, but it was a single provider and faced no competition. This is a recipe for slowing innovation, and that’s exactly what happened. Europe was a leader in commercial space services and was leapfrogged by the US.”

One attempt by ESA to address this is the Commercial Cargo Transportation Initiative, which will provide private companies with support to provide transport to the International Space Station (ISS) from 2028. ESA is currently evaluating the results of the first call for proposals.

Nicoli believes the concept is promising, but uncertainty remains around the level of funding and with the ISS due to close by the end of 2030, about future contracts.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.