The country wants to double collaboration with the EU, and Kiwi researchers are excited about starting new projects. But the challenge of controlling costs, parliamentary scrutiny and sheer distance could all present obstacles

It takes at least 30 hours to fly halfway round the world from Brussels to Wellington, with several jetlagged stops on the way. In fact, with most of the EU exactly 12 hours behind New Zealand, even scheduling a Zoom call is a challenge.

But this hasn’t stopped the country associating to Horizon Europe, the EU’s €95.5 billion research and innovation scheme, as Brussels seeks to open up the programme to countries all over the world in a push to build a global R&D coalition of “like-minded” democracies.

Association negotiations, successfully concluded last December, pave the way for researchers in New Zealand to join many Horizon projects on the same terms as their counterparts in the EU.

This has Kiwi academics excited about a new era of collaboration on opposite sides of the globe. The New Zealand government is hoping that association will more than double the number of joint projects researchers embark on, at least in the parts of the programme where they are eligible.

“This is an extraordinary opportunity,” said Michael Witbrock, an artificial intelligence professor at the University of Auckland. “Now that the logistical barriers are falling away, I'm already reactivating old connections and looking for opportunities to form new ones, and tentatively planning exploratory visits.”

New Zealand is the first country to agree to associate to Horizon Europe under the Commission’s policy of global expansion, which has taken on even more importance as the EU tries to find science and technology partners in a world where research is increasingly geopolitically fraught.

The Commission has become more wary of collaborating with China and has blocked neighbouring Switzerland and the UK from associating until their wider relationship with Brussels is settled.

After New Zealand, Canada is in the most advanced form of association negotiations, while South Korea and Japan are in exploratory talks. The Commission has also tried to entice Singapore and Australia, but they haven’t yet made it to the negotiating table, at least officially. So the details of the New Zealand deal have implications for the Commission’s entire global strategy.

Uncapped funding

One of the trickiest negotiating points is how countries like New Zealand can control the cost of associating. When not associated, researchers in New Zealand can still join Horizon calls, but have to find their own funding.

But after association, they get funded automatically (and can coordinate projects), with the New Zealand government paying into a common pot in line with how much money its researchers win from the programme.

Witbrock once worked as a technical director of a project under the 2007 – 2013 R&D Framework Programme 7, while based in the US. It involved setting up a European subsidiary organisation, and was “logistically extremely complex”, he said. “Having a mechanism for direct involvement, on an equal footing, will, I think be enormously beneficial in driving collaboration.”

So association sweeps away the bureaucracy of needing to line up multiple funding sources and set up complex structures, but also puts New Zealand’s treasury on the hook for a theoretically huge bill if its researchers do well in the programme.

A blank cheque?

The good news for Kiwi scientists is that both the Commission and New Zealand government say that in theory, there is no limit on how much Wellington will pay out to fund their participation.

“The agreement does not include a maximum amount or ‘cap’ to New Zealand contributions, in the interests of the programme being fully competitive or open to the best applicants,” confirmed Loveday Kempthorne, international science partnerships manager at the ministry of business, innovation and employment, which handles science and technology policy.

This blank cheque also gives partners “maximum certainty” they can collaborate with New Zealand, she said.

However, if Kiwi researchers win more grants than expected, and costs “escalate beyond expectations”, Kempthorne said there are a “range of options to remedy the situation”. But she declined to give more details while these are being “finalised”.

So it’s unclear as yet how Wellington will control costs, although one Brussels insider speculated that in a relatively small country, the government would be able to informally pressure universities to ease up on Horizon applications if costs begin to spiral.

Political concerns

This lack of transparency has ruffled feathers among politicians in Wellington. Judith Collins, who until a recent political shakeup was the science spokeswoman for the opposition, urged the government to brief other political parties what association precisely will entail.

“Without knowing the cost to New Zealand, nor the obligations on New Zealand, it is difficult to provide you more than a general agreement that association with Horizon Europe would be a positive step for both New Zealand and Europe,” she said.

The Wellington government said it cannot make the exact details of the agreement public until it has been consulted on and approved by ministers and both parliaments.

Meanwhile, the deal also faces questions in the European Parliament. MEPs have threatened to block association because they fear the deal gives the Commission control in perpetuity over whether New Zealand joins future framework programmes, depriving Parliament of a say.

Doubling up

New Zealand hopes participation will at least double during Horizon Europe – although only in the part of the programme it is associated to. It is joining pillar II, which tackles global and industrial challenges through consortia of businesses and academics, and makes up the majority of the programme’s budget.

During the seven years of Horizon 2020, Horizon Europe’s predecessor, New Zealand won 23 grants in this pillar. By contrast, the ministry hopes the country will win 40-50 grants during the remaining five years of Horizon Europe. It’s expecting about 220 applications, and a success rate of 20% (so far, for the whole programme, they are around 16%).

“We are certainly putting the message out to our researchers that they will be able to lead research programmes and consortia,” said Richard Blaikie, deputy vice chancellor at the University of Otago, which joined eight projects under Horizon 2020. The challenge is getting European universities to understand Otago’s strengths – which are in health, physical and environmental science, he said.

Kiwi strengths

Even without Horizon Europe association, the EU was already New Zealand’s strongest academic partner. In all, 19.5% of publications by its researchers had an EU-based co-author (before the UK withdrew from the EU in 2020, this figure was even higher, at 26%), according to the business ministry.

This is slightly higher than for the US (18.6%) and about double the rate of collaboration with China (11.8%).

As for the fields in which this collaboration takes place, Kempthorne said the strongest links with the EU are in health, wellbeing, and climate action.

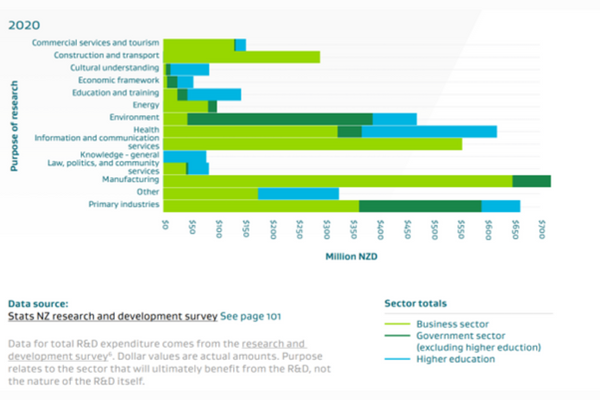

The most recent data from the New Zealand government gives a glimpse into where New Zealand’s R&D system excels: the environment and health have plenty of state investment, but the private sector also focuses heavily on ICT, manufacturing, and primary industries like agriculture, logging and mining.

Another aspect of Kiwi research that European partners will have to wrap their heads around is a big focus on Māori issues. Engagement with Māori groups, as well as a focus on well-being, has transformed the way research is done in the country, said Patrice Delmas, an Auckland computer scientist, and co-design of studies with local communities has become “critical”.

Under Horizon 2020, for example, the Basque Centre for Climate Change partnered with Otago on a project to try to learn from the Māori on how to manage freshwater sources.

Does distance matter?

New Zealand’s association poses another question for researchers in the EU: in an age of video conferences and remote working spurred by the pandemic, does it still matter that New Zealand is on the other side of the world?

Kiwi academics point out they are more than used to long haul flights, and are frequently in Europe for conferences, combining long trips with stops in North America and Asia.

“Face-to-face relationship building is important,” acknowledged Witbrock. But, he added, “our researchers are used to travel to maintain collaborations; for many this will just involve bundling Horizon Europe activities with others.”

During a Horizon 2020 project, European colleagues of Delmas visited New Zealand in one-month stints to build up personal relationships. If visitors from the EU plan these trips “carefully”, he said, they can enjoy the country’s warm weather – escaping the European winter.

A 12-hour time difference means that any online meetings will always have to take place outside normal working hours. But this can work to a project’s advantage, as it allows teams to work on a problem almost 24 hours a day. “We see the time difference with Europe as an advantage as we can work while you sleep and vice-versa, this can allow projects to progress faster,” said Delmas.

Dreams of the ERC

Despite association to pillar II, New Zealand academics cannot apply on an equal footing to the rest of the programme. Most notably, they cannot win grants from the European Research Council (ERC), which sits in pillar I, dedicated to curiosity-driven science – unless they move to Europe.

There’s hope on the Kiwi side that a successful stint in Horizon Europe could pave the way for full access to the ERC in the future.

“The European Commission invited New Zealand to associate to pillar II, and this was the basis of exploratory talks and subsequent negotiations,” said Kempthorne.

But as “awareness and familiarity in the New Zealand research sector grows”, the country’s participation in other aspects of Horizon Europe “may also grow,” she added.

Association to pillar II is a “sensible first step”, Blaikie said. “We would anticipate that success in pillar II might lead to future expansion for New Zealand researchers to allow access to the ERC funding mechanisms in future.”

But allowing the rest of the world access to the ERC, a crown jewel of the framework programmes set up to bring the very best frontier science in the world to Europe, might be a step too far for Brussels.

A Commission spokeswoman simply said that pillar II is “the most relevant collaborative part of the programme.”

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.