With promising results in animals, some scientists say research should focus on slowing ageing, rather than curing individual diseases

Photo credits: Sports Photos / BigStock

Last year, researchers published an analysis that made grim reading for anyone hoping to live a much longer, healthier life this century.

Human life expectancy has all but hit a wall, it argued. After huge gains in the twentieth century as public health improved and preventable diseases were eradicated, progress in the rich world has now slowed as we approach what appears to be a natural ceiling on how long we live.

Major gains in life expectancy this century are “implausible,” the study found, unless, crucially, “the processes of biological aging can be markedly slowed.”

Lead author S. Jay Olshansky, a public health professor at the University of Illinois Chicago, says this has profound implications for how we should fund health research.

Instead of ploughing money into curing individual diseases such as cancer or Alzheimer’s, we should focus instead on understanding and slowing the underlying ageing processes that lead to them, he argues. Just 0.08% of the EU’s funding for research consortia is spent on understanding the biology of ageing, for example.

Talk of slowing ageing can produce understandable scepticism. Cheating death has been a futile preoccupation as old as humanity, and the anti-ageing field is notoriously littered with quack treatments, messianic dreamers and unfulfilled scientific promises. Some Silicon-Valley types have adopted outlandish, scientifically questionable daily routines to keep themselves young.

But the past few years have also seen an upswell of serious interest in ageing and potential treatments, with several new books on the topic.

Anti-aging advocates have also reached the corridors of power. In June, the new US administration of Donald Trump appointed a proponent of anti-ageing therapy, Jim O’Neill, as deputy secretary at the Department of Health and Human Services, a powerful role in determining the US’s health science priorities, although Trump is planning severe cuts, including to ageing research.

But most importantly, scientific evidence has stacked up that various drugs and other interventions can prolong life in animals.

Yet there hasn’t been a consequent shift in scientific priorities to see if these treatments might work in humans, and to understand the underlying biology of ageing, say Olshansky and other scientists in the field.

While things have improved in the past field years, “the field is indeed underfunded,” he said.

“Until a spending shift happens, we will continue to focus our efforts on addressing the consequences, rather than the root causes, of ageing ill-health,” warned a report by the UK’s Royal Society last year. British lawmakers have criticised the country’s research funding for being overly targeted at “specific diseases,” and want it refocused on “biological processes underlying ageing as a priority.”

“You can certainly say that ageing science has been underfunded and needs to be increased,” said Andrew Scott, an economist at the London Business School who has calculated that delaying ageing would bring far greater economic benefits than eradicating individual diseases. Scott would like to see all health research better funded, but if this isn’t possible, money should be diverted to ageing from areas such as cancer or dementia.

We can’t know for sure if a scientific push to slow ageing will pay off, acknowledge advocates. But given promising results in animals, diminishing returns treating individual diseases, and the growing economic burden of an elderly population, it’s time to seriously try, they argue.

Life expectancy is still increasing, but at a much slower rate than in the 20th century.

No more Whack-A-Mole

The basic argument of ageing researchers is that treating individual diseases only buys older people a short amount of time, often in poor health, before another age-related disease strikes.

“Someone comes in with acute heart attack, and you do a triple bypass, and they go home, and everything's fine, but then they may get dementia,” said Lynne Cox, an ageing expert at the University of Oxford. “It's like playing Whack-A-Mole.”

Take cancer, for example. Olshansky and several other researchers have estimated that even if we completely cured cancer, this would add just two to three years extra human lifespan in the rich world, because at the age cancer typically hits, so many other things begin to break down.

Promising animal results

So far, scientists have discovered 12 biological hallmarks that appear to drive ageing. These include cell senescence, where cells stop dividing, as well as chronic inflammation and the erosion of telomeres, the caps that keep our chromosomes protected.

How these processes interact, and their individual contribution to ageing, is still unclear, let alone how to stop them. In other words, there is very unlikely to be a single off-switch for ageing.

Despite this complexity, some drugs have shown promising results in animal trials, extending not just lifespan, but preventing diseases of ageing too, said Cox.

Rapamycin, a cheap, off-patent immunosuppressant, is shaping up to be one of the most promising candidates. A meta study published in June found it produces a “significant lifespan extension” in all kinds of animals, from fish to dogs to rhesus monkeys. Rapamycin is now being trialled to see if it can slow human Alzheimer’s.

Some of this work is happening in the EU. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Biology of Ageing in Cologne found that combining Rapamycin with another drug, Trametinib, normally used to treat cancer, extended the lifespan of mice by 30%. One of the researchers behind the study has said there’s a good chance this treatment would work in humans too.

The long-term potential of ageing therapies is still hazy. Some more visionary advocates dream of living for millennia. But most researchers in the field are much more cautious, hoping for an extra decade or two of lifespan in good health.

Metformin

But scientists trying to test these drugs on humans say they are plagued by insufficient funding.

Nir Barzilai, director of the Institute for Aging Research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, is trying to raise the money to press ahead with Targeting Aging with Metformin (Tame), a phase three trial to see if the drug can slow down ageing in humans, as some studies suggest it appears to in monkeys.

But private firms are not interested in contributing, Barzilai said, because metformin, originally used to treat diabetes, isn’t patentable. “No pharmaceutical is interested in helping us,” he said.

Initially, a billionaire was set to fund the research – Barzilai declined to say who – but then he “lost his money,” he said.

A private foundation stepped in, but then decided to fund only a third of the trial. “So we're trying to get the other two thirds, and we're making some progress,” he said. He estimates the trial needs around $8 million annually for four to five years. Without more money, the Tame trial will have scale back its ambitions, testing metformin on fewer patients, he said. “The promise versus the funding is ridiculous,” he said.

Another major US study, looking at the impact of rapamycin on dogs, has also struggled to raise money.

European (lack of) cash

So how much do public bodies spend on ageing biology?

In Pillar 2 of the EU’s research programme Horizon Europe, ageing appears to be an afterthought. This part of the programme funds continent-spanning research consortia and receives the lion’s share of its €93 billion total budget.

Since the programme started in 2021, Pillar 2 has awarded money to six projects looking at underlying ageing biology, according to a European Commission spokesperson.

These six projects have received €23 million in total, which amounts of 0.48% of the €4.8 billion Horizon Europe has so far dished out on health topics, and just 0.08% of the €27.9 billion spent through Pillar 2 as a whole. For comparison, oncology has received €193 million so far, and the EU has launched an entire mission to tackle cancer.

In the Commission’s recently released plans for the next Framework Programme, which will start in 2028, ageing is not mentioned. However, there was a brief mention of a “moonshot” project on “regenerative therapies,” although the Commission declined to clarify whether this could involve anti-ageing research.

At the European Research Council (ERC), the record on ageing is much better. Since 2014, it has awarded a total of €247 million to 114 ageing biology projects. That’s 4% of the ERC’s €6.2 billion life sciences spending, and 1.1% of the council’s €22 billion overall spend.

The US picture

Meanwhile, the US has its very own National Institute of Ageing (NIA), part of the National Institutes of Health.

This sounds promising, but the NIA is a classic example of how ageing research is underfunded, argues Andrew Steele, a science writer who in 2020 published Ageless, a book that explores the potential of anti-ageing medicine.

For a start, its overall budget this year is $4.5 billion, significantly less than the National Cancer Institute, which received $7.2 billion.

But drill down into the NIA’s budget, and the picture looks even worse, argues Steele.

Only $346 million of the institute’s budget goes towards ageing biology itself. That’s 0.8% of the entire budget of the National Institutes of Health, which dominates biomedical research in the US.

At the NIA, more than twice as much is spent on behavioural and social research as ageing biology. And the majority of the institute’s budget goes on “neuroscience,” which is primarily focused on Alzheimer's disease, rather than ageing as a whole.

For Steele and other scientists, this is an absurd misallocation of resources. If the NIA actually spent its budget primarily on ageing biology, “that would allow us to tackle not just cancer, not just dementia, not just heart disease, but all of these things at once,” said Steele.

Asked why the NIA distributes funding in this way, an NIH spokesperson said that Alzheimer's disease funding was “unique” at the institutes. Research at other institutes, on diabetes for example, might also aid fundamental understanding of ageing, they added.

Trump also wants to reduce the NIA budget, from $4.5 billion this year to $2.7 billion in 2026 as part broader cuts, although Congress might yet blunt these reductions.

Charity lacking

Meanwhile in the UK, where the calls for more ageing funding have been among the loudest, the country’s chief public research funder, UK Research and Innovation, said it couldn’t provide comparative funding data between ageing and diseases such as cancer.

Another problem for the field is that ageing finds it “hard to capture the imagination” and attract charitable donations from the public, points out Deborah Dunn-Walters, an ageing researcher at the University of Surrey. When people want to collect money for deceased relatives, they typically fundraise for research into the immediate cause of death, like cancer.

Billionaires to the rescue?

Various billionaires, including Amazon founder Jeff Bezos and Meta founder Mark Zuckerberg, have reportedly ploughed money into ageing-related start-ups including Altos Labs, which is based in the US and UK, and focused on cell rejuvenation.

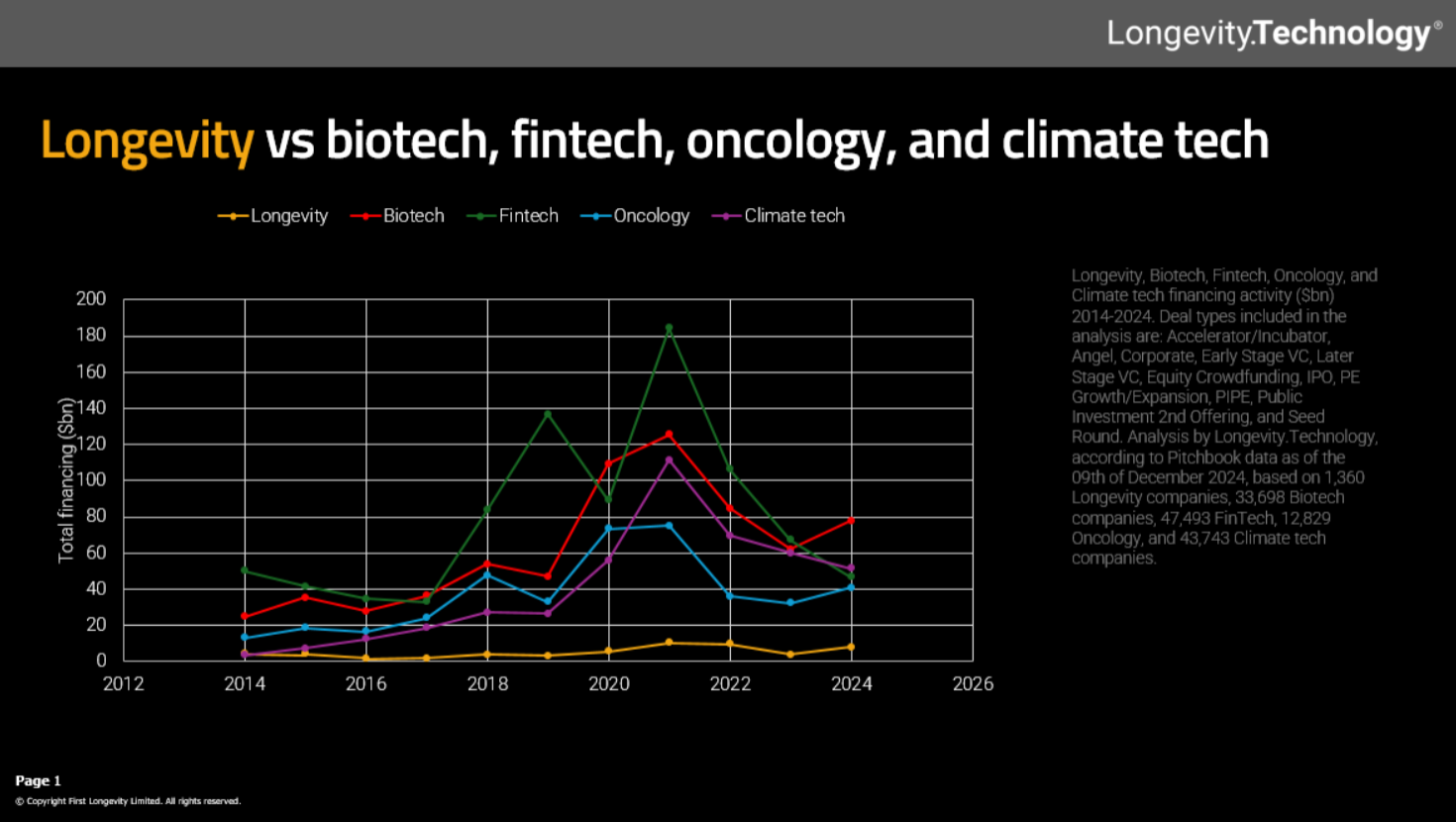

Far more private money still flows into oncology than longevity. Source: Longevity Technology

However, a closer look at private investment data shows longevity companies are neglected compared to, say, cancer treatments, according to statistics from Longevity Technology, which tracks the industry.

Predictably, the EU lags far behind the US even on this relatively meagre funding. The US accounted for 83% of longevity private investment in 2024, a total of around $7 billion, whereas the EU got just 10%, according to Longevity Technology figures.

Scott, the longevity economist, is also worried that if private money is allowed to dominate longevity research, it risks prioritising expensive treatments that extend lifespans for the rich.

“I think the larger welfare gains come from compressing morbidity,” he said, meaning using therapies to help people live more of their lives in good health, rather than extending lifespan. “Public funded research is more likely to go down that route.”

Administrative hurdles

It’s not just money that advocates say is holding back human anti-ageing trials. Regulatory issues also abound.

Typically, before approving trials, regulatory agencies need to know which specific disease a new treatment targets, called an indication. But so far, ageing as a whole isn’t considered an indication.

What’s groundbreaking about the Tame trial, said Cox, is that the US Food and Drug Administration is allowing the study to see whether metformin protects against one of a number of age-related diseases, not just one, as a normal trial would. “That’s a big deal”, she said.

Related articles

- Commission cuts funding planned for Horizon Europe health calls

- Viewpoint: Transylvania bets on med-tech innovation

- Trump halts new NIH grants to international health-research partners

One way around a lack of indication is for pharmaceutical companies to trial anti-ageing drugs on a specific condition, such as heart disease, and get approval for that specific condition. Then, it could potentially be prescribed more widely for its broader anti-ageing benefits, rather like Ozempic went from being a diabetes treatment to a weight-loss drug.

This is the approach private firms are taking for now, said Phil Newman, chief executive of Longevity Technology.

“All of these companies are looking to identify existing diseases as their therapeutic endpoint, so that they can obviously get to market,” he said.

Biomarkers needed

Another barrier to trials is their sheer length: if people start taking a drug at 50, it could be another three decades before they do (or don’t) develop the age-related diseases the drug is supposed to prevent. “No pharma company is going to wait 30 years for a trial,” said Cox.

To get round this problem, researchers are hunting for biomarkers, proxies that can indicate how quickly someone is ageing, but without having to wait for diseases to emerge. For heart disease drugs, say, cholesterol is a biomarker that can tell regulators that a treatment has good prospects of working, Steele said.

Cox is trying to convince the UK regulator to accept biomarkers as reliable proxies. Barzilai also hopes to use the Tame trial to gather biomarker data.

But with Tame still scrabbling for funding, Steele is desperate for a big funder such as the EU to step in and fund other major studies of potential anti-ageing drugs that would give reliable biomarkers, meaning future trials would be far quicker.

He thinks this would cost in the order of $70-100 million, a “drop in the ocean” for the NIH or EU budget. Barzilai has listed 11 other potential anti-ageing drugs that could benefit from big trials, as he is attempting to do for metformin with Tame.

Accurate biomarkers would be a “very important trigger for everybody in the space,” said Newman of private longevity firms.

Return on investment?

Though some anti-ageing drugs work in animals, there’s still no track record of them improving human health. For this reason, a major shift to ageing research would be something of a gamble.

Anti-ageing medicine has tremendous potential, said Dunn-Walters, but the actual return on investment is still “largely finger in the air” for now.

This question of reallocating funding is indeed “difficult” and “somewhat subjective,” said Venki Ramakrishnan, a Nobel Prize winning structural biologist, who last year published Why We Die: The New Science of Ageing and Longevity.

“It is hard to know how much to balance research on aging versus, say, cancer or indeed infectious disease that still plagues much of the poorer parts of the world such as Africa or Asia,” he said.

Take the moonshot

There is also uncertainty over the extent to which ageing treatments would simply shunt frailty and ill-health a decade or two later. “Are we just postponing stuff?” Dunn-Walters asked. “Having said that, I don't think that that's any reason not to try.” Postponing frailty by a decade, say, would still mean people live a greater proportion of their lives in good health.

Steele acknowledges the lack of certainty about whether investing in anti-ageing will pay off. “There is always a point in research when you've got some promising things in the lab, but it's all a bit speculative,” he said.

But with a wealth of results in animals, it’s now worth pressing ahead into humans. “Ageing biology has got more than enough evidence now that it's at a stage where we can take that moonshot,” he said.

Cost-to-research ratio

One way of quantifying whether a disease is under-researched, suggested by last year’s Royal Society report, is to compare the costs it imposes on society against R&D spending on a cure.

Take cancer in the UK, for example. Totting up direct health costs, social care, informal care costs, and lost productivity, the disease costs the UK £18.9 billion a year, according an estimate in the Lancet last year. Meanwhile, in 2022 the country spent £469.3 million a year on non-commercial research fighting the disease, making a cost-to-research ratio of 2.5%.

The social cost of ageing is, by definition, much higher, because old age is the overwhelming risk factor for diseases such as cancer. Other age-related conditions such as arthritis also cost the UK billions of pounds a year. Cox has calculated a cost of £63 billion a year, meaning that if ageing research was funded in line with cancer, this would imply an annual expenditure of £1.5 billion.

This is just one, rough estimate, but it’s orders of magnitude above what even the NIH or EU spend. Meanwhile in the UK, figures aren’t even available, but the size of calls for ageing biology research are “trivial,” Cox said, in the low millions of pounds at best.

Should we live longer?

Any push for anti-ageing medicine would, however, have to contend with a common objection over the impact it might have on the planet: with humans consuming ever more of the earth’s resources, do we really want them to stick around for longer than they currently do?

This is a much bigger, thornier policy question; Steele tackled some of the most common objections to living longer in a free chapter of his book.

But as policymakers and the public increasingly fret over declining birth rates and ageing populations, Steele says he now hears the crowded earth objection far less than he once did. “That whole debate really seems to have transformed, literally just in the last few years,” he said.

Anti-ageing research could be a way for European governments to ameliorate the enormous social care, health and pensions costs of an ever-older society. “The time is right for thinking about aging biology as a potential solution,” he said.

Mentality change

For scientists as well as policymakers, the challenge may be changing not just budgets, but mindsets: viewing ageing not as something inevitable, but a process that could be slowed, even stopped, say ageing scientists.

Even now, Cox thinks there’s still a lot of scientific doubt that research could one day slow human ageing. “There are a lot of [researchers] who are really sceptical,” she said, who believe that “aging is just observational science.”

The payoffs remain unclear. But in the future, anti-ageing drugs could ultimately become as common, and unremarkable, as routine medicines for high blood pressure today, said Richard Faragher, an ageing researcher at the University of Brighton.

In the 1960s, because it was so commonplace, high blood pressure was seen as “benign” and not worthy of treatment. The arguments against trying to treat ageing now are “highly reminiscent” of those against treating high blood pressure in the 1960s, he said.

At first, people thought nothing can be done, then they argued nothing should be done. But from today’s vantage point, this inaction looks utterly naïve, Faragher said, a view we may one day have of ageing.

Editor’s note: this article has been updated to include more recent figures from the ERC.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.