The 2023 Regional Competitiveness Index placed Romania last, but those working to boost innovation in its regions believe the future could now be in their own hands

In the recently published EU Regional Competitiveness Index, ranking how attractive an area is for people and businesses, Romania ended up with six regions in the bottom 10.

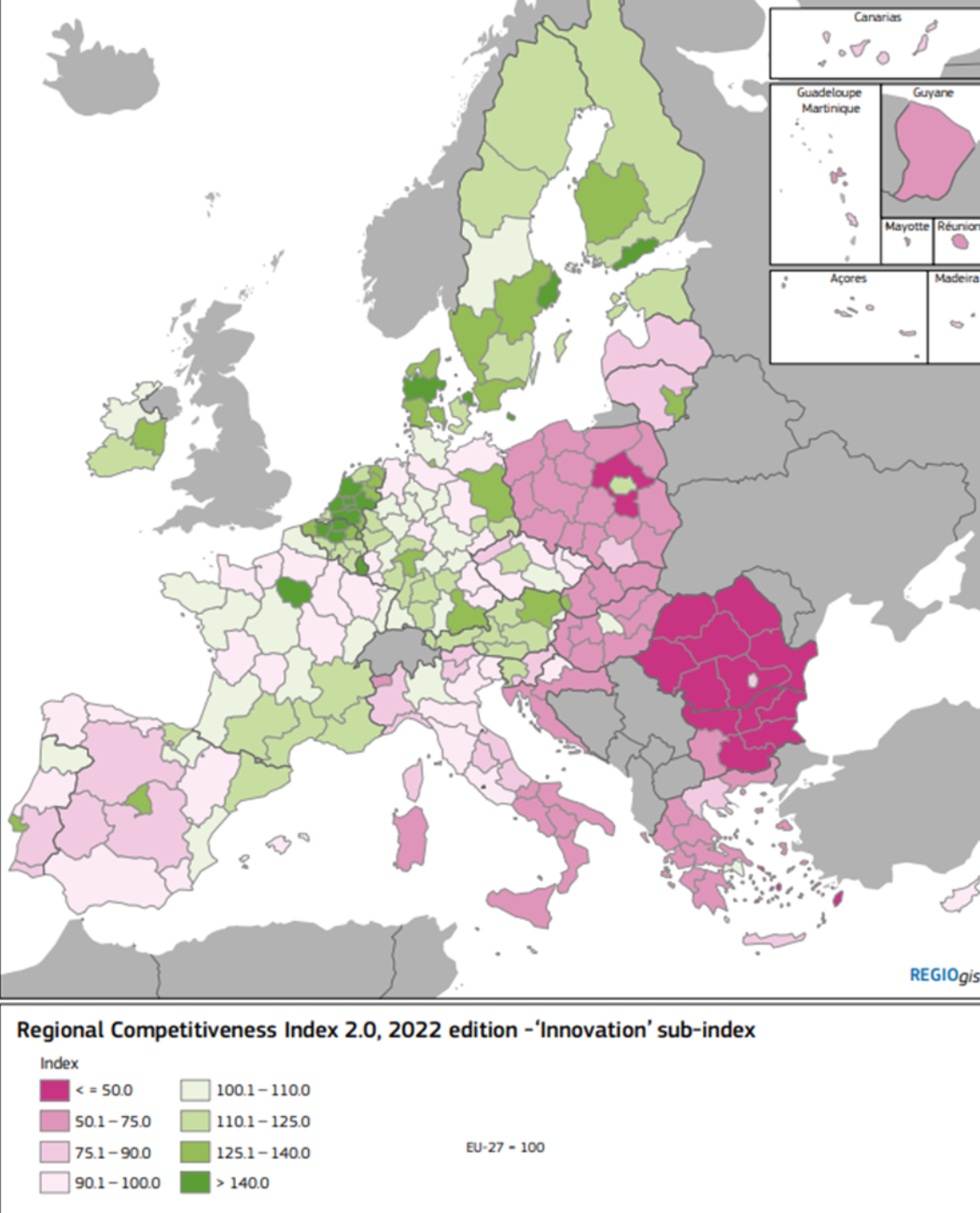

The whole country, with the exception of the region around the capital, Bucharest, is coloured a dark shade of pink on one of the maps in the index, indicating a low level of innovation. This is in stark contrast with northern Europe, around the Netherlands and Scandinavia, where every single region is high in the ranking.

This does not sit well with Bogdan Chelariu, head of the Brussels office for the North East Regional Development Agency of Romania, the region that finished second bottom in the index. But now he is optimistic that regions are being given the means to turn things around.

In particular, Chelariu points to the new Regional Innovation Valleys (RIV) initiative announced by EU research commissioner Mariya Gabriel at the end of March, with two calls worth €170 million.

This is supposed to build on previously launched initiatives such as the Partnerships for Regional Innovation (PRI) and Smart Specialisation strategies (S3), all with similar goals to help lagging regions catch up.

For Chelariu, the regional valleys initiative is different from what went before, because it puts the onus of managing funds on the regions themselves. “This could have huge potential,” he said. “Before we had this excuse that [a funding scheme] was not going well because the designers didn’t know the local ecosystem, now we will not have this excuse,” he said.

The goal of RIV is to have 100 regions signed up and participating in interregional and cross-border collaborations. The regions that have already participated the S3 initiative or the PRI initiative, which is essentially just a guide book or methodology for how regions can improve their innovation ecosystems, will fare better at utilising the new RIV scheme, Chelariu said.

It is early days for RIV, with the first two calls not going out until next month, but Chelariu is optimistic it will work out well.

Utrecht tops the charts

At the other end of the EU’s competitiveness spectrum, northern European countries dominate, with Utrecht the number one most competitive region, according to the index. It joins four other Dutch regions in the top 10, which includes two Belgian regions and one each from France, Sweden and Denmark.

Anton Pijpers, president of Utrecht University’s executive board, said the secret behind the region’s success is its focus on creating collaboration between government, industry and academia.

While part of the region’s success is down to its location in central Netherlands and its links to major European hubs, more important is the fact that everyone is pulling in the same direction. “We have really invested a lot in strong collaboration,” he said. “Even our local football team, FC Utrecht, is involved.”

Rank disincentives

While he recognises there is value in the competitiveness index, Chelariu is concerned that it reinforces the narrative in the EU that the peripheral regions are all unattractive and non-innovative, while those at the heart of the bloc are always at the top.

“This bothers me,” Chelariu said. “The index basically shows that if you are far away you are less innovative no matter what you do.”

This could have a negative effect on moves to improve the competitiveness of a region, by demoralising rather than encouraging innovation stakeholders to act. “If I translate this example to my region, we spend a lot of energy convincing our stakeholders to be more active in innovation, and then when a report like this appears, it is a message that their place is not there,” said Chelariu.

“Of course, you cannot hide these reports and it is good to know the reality, but I would be more careful in how the information is presented. There is still a lot of work to be done so that it does not harm efforts to engage local actors,” he said.

When the 2023 competitiveness index was published in March, Eleni Papadimitriou, scientific officer at the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre and one of the authors, defended its usefulness.

“Composite indicators are controversial, many hate them and many like them,” but they are a “powerful tool to synthesise big picture data,” she said.

“This helps our policymakers summarise […] complex information,” said Papadimitriou. “Ranking regions forces governments and institutions to acknowledge where they stand.”

Challenges on the ground

While it is true that the north east region of Romania is remote from the mainstream, geography is not the only factor. Chelariu highlighted two key weaknesses that must be addressed, a lack of knowledge transfer and an overreliance on EU cohesion funds.

There is not enough networking and communication between universities, research institutions, companies and start-ups in the region, meaning solid research rarely finds its way to the local market.

And as an added complication, much of the region’s research infrastructure is funded by EU structural funds. While it is undoubtedly a bonus to have EU money poured into the local research system, it is not always easy for private companies to access these facilities, due to strict laws around what publicly funded infrastructure can be used for.

“That’s a huge bottleneck that exists in places with big research infrastructure but no protocol on dealing with the private sector,” Chelariu said. “In western Europe generally, such projects are not [financed] through structural funds, so there is never a debate about public money or competition rules.”

With the launch of RIV, Chelariu is optimistic things are on the up. “I hope the region will improve. Starting from this year we have some tools that we did not have in the past, or which were not in our control. We wished for this and now it is happening and so it is fully our responsibility to make changes,” he said. “No more excuses.”

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.