The EU’s push for ‘strategic autonomy’ overlooks its longtime underinvestment in military and civilian R&D, and a need for broad market reforms, argues US innovation scholar Charles Wessner

Charles Wessner, an innovation policy scholar

This article is part of a series of opinions Science|Business is publishing on the EU’s strategic autonomy agenda, and its impact on global R&D. A complete report will be published and discussed at the annual Science|Business Network conference 7 February.

In its effort to increase the strength and competitiveness of its technology industries, the EU has been moving towards a policy of ‘strategic autonomy’. In theory, that’s good; EU member states are vital US allies, so what strengthens Europe could also strengthen America. But the way this policy is developing raises concerns, and risks repeating old mistakes.

That the EU should want more autonomy right now is no surprise. It is probably fair to say that the last 12 months have revealed a shocking level of dependence by many European countries for commodities and technologies critical to their security. Most of all, the war in Ukraine has laid plain the near-total dependency of some countries on Russian gas and oil. But when it comes to science and technology, the way the EU has reacted has an exclusionary element, embedded in a transactional approach to S&T cooperation. For instance, efforts to limit participation of Swiss and British researchers in EU R&D projects may substantially reduce the EU’s capacity for broad advances in technologies like artificial intelligence and quantum computing and communications.

Strategic autonomy also reflects a growing focus on China’s rising tech strength. Some of this is propelled by China’s own drive for self-sufficiency. One can understand Beijing’s concerns over the numerous economic choke points in its economy, be it oil or semiconductors. However, the mantra of free trade and the expectation that, once in the World Trade Organisation, China would become rule-abiding partners “just like us,” has certainly fallen by the wayside in the face of Chinese industrial policies, espionage, and massive mercantilism. So the fact that European policymakers don’t want to be the last to be dependent on global supply chains is understandable. But it seriously understates the reality of global interdependence.

The importance of interdependence

Global interdependence is far from over. A striking example is the mutual dependency that is derived from Taiwan’s success, largely with Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC), in developing the most robust and the most advanced semiconductor manufacturing capabilities in the world. Too often commentators talk about the most advanced chips being just 90 miles off the coast of China. But the idea that in a lightning invasion, China could seize TSMC is debunked in a new book, Chip War, by Chris Miller, associate professor of International History at Tufts University. He points out the fragility of the equipment in the world’s most advanced semiconductor fab, its vulnerability to sabotage let alone bombs, and its extreme vulnerability to supply disruptions of the materials and chemicals and maintenance required for the world’s most complicated machines to function. The key point is that China itself is hugely dependent on TSMC. Any disruption to its supply would have a massive impact on the Chinese economy. Miller suggests this impact would compare to that of the Great Depression. His argument makes sense. We can only hope that the Chinese leadership appreciates it, which seems very likely.

The main point, however, is that the US, Europe and China are all locked into mutual dependencies in the semiconductor supply chain for equipment, materials, production, assembly and, not least, final markets. To the extent that we can tighten supply chains between the US and Europe, our economic security will be mutually enhanced. But we will be a long way from autonomy, which of course is arguably a good thing.

A bigger issue: money

In my view, however, a major problem with the EU’s autonomy policy is its lack of scale or focus, particularly with regard to deployment of competitive products.

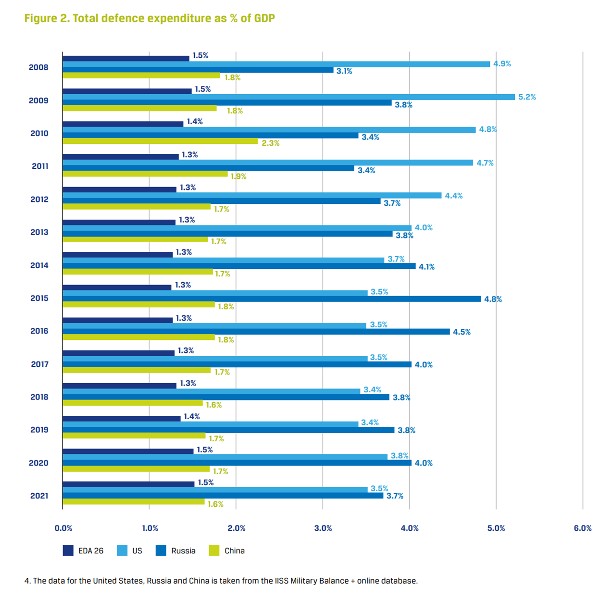

Defence technology is an example. Europe simply does not spend enough on it. Many major US innovations have emerged from defence spending. Think of radar, satellites, atomic power, computers, semiconductors, aerospace, and global positioning systems in the Cold War, and now quantum computing, artificial intelligence and vaccines, all of which have been advanced by military spending and needs. The goal was not to develop civilian applications but to defend ourselves; but the result was a host of technologies that could be used for commercial applications. Though they have recently pledged an increase, the fact remains that over the past decade the key European allies have pegged defence spending at no more than 1.5% of gross domestic product – less than half the typical US budget, and less still than Russia.

Europe’s lagging defence budget

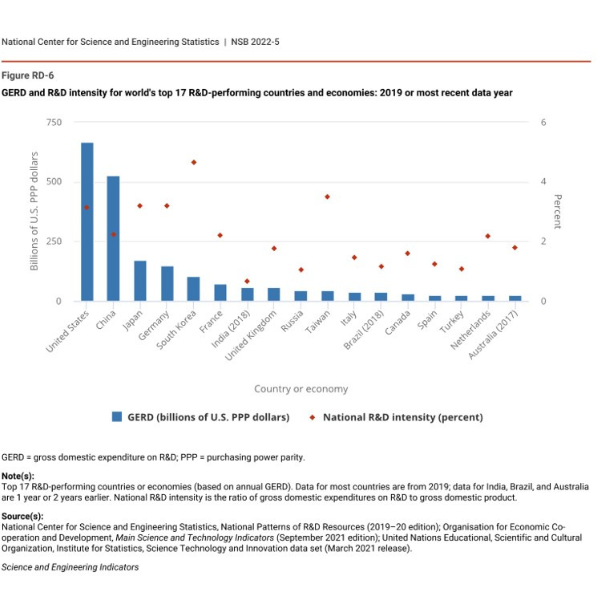

At a more fundamental level, there are great disparities in funding for research among the major regions. Despite the plethora of EU-level R&D projects, the levels of funding remain relatively modest compared with the US, not to mention China.

R&D spending across major economies

The EU Horizon Europe research programme, however well-conceived, has €95.5 billion to spend – a considerable sum, but one that, when divided over seven years and 27 member states, rapidly loses scale. The good news is that the EU programmes provide new funding for new projects able to bring together European researchers in collaborative projects. The criticism is that too often, the projects are focused on building European cooperation instead of cutting-edge science or, even better, prototypes of products to address health, climate, and the digital economy, as well as new domains like quantum computing and communication.

Moving from lab to market

Another major challenge to European autonomy is the difficulty of transferring promising ideas to the market. Some excellent programmes exist, like the proof of concept awards for projects funded by the European Research Council. But the funds provided are less than what’s needed; there is limited provision for staging funding as work progresses; and there is little institutional support to encourage private participation with matching funds. With respect to private investment, the good news is that venture funding in the EU has increased substantially, notably in countries such as France and Germany and the UK before Brexit. But venture capital comes in many forms – and risk capital, in particular, is hard to obtain. The problem is that too many venture firms are not actually venturesome. Still, the growth in risk capital funding is a very positive sign for the future growth of innovative firms.

But there remain major structural problems in creating a more innovative and therefore a more autonomous Europe. Effective autonomy requires a dynamic innovation system with incentives and institutional and policy support for innovation. For example, one of the great advantages of the US innovation system is its gentle bankruptcy laws. Chapter 11 allows entrepreneurs to take risks and attract investors and, in case of failure, it enables them to reboot and try again. The idea that Californians don’t care about failure is a myth. It’s the consequences that are often so different compared to many European countries, not only financial but reputational, which in turn affects their ability to raise capital again. This raises risks and costs for entrepreneurs.

A broader recipe for success

The truth is that Europe needs more strategic autonomy. To win it, It must be collectively willing to make the investments needed to achieve greater autonomy in research and in defence. Especially in a geopolitically uncertain world, Europe needs greater investments in defence research. Member states need to advance their own defence production and, in the current crisis, should not hesitate to acquire high-performance weapon systems. Finland is a superb example of a country with excellent reseach and commercialisation, coupled with a generous social safety net – but also a well equipped and well trained military.

To exploit investments in defence R&D, Europe needs a flexible, dynamic innovation ecsystem, which is more business friendly, with less not more regulation, and an underlying policy framework that allows for risk-taking and provides the capital to take those risks.

Europe could also benefit from more transatlantic cooperation — as could the US, given the challenge posed by Russia and China — and this cooperation needs to be picked up with a sense of urgency. While recognising European concerns that American mega-companies may capture the technological heights of the next revolution, it is nonetheless important that these actors be western companies: allies in war and peace. It is important to keep in mind that leading US companies, however recalcitrant, will respect the law. It’s worth keeping in mind that the greatest accomplishment of the European Chips Act, at least so far, is a decision by US chip giant Intel to make massive investments across Europe in semiconductor packaging, research, and fabs.

In short, Europe can benefit from the right sort of strategic autonomy. To do so the member states need to invest, and make policy changes to more fully capture the benefits of those investments, while also fulfilling the fundamental obligation of being able to defend Europe’s freedoms and way of life for the next generation.

Charles Wessner is an innovation policy scholar. He founded and directed the Technology, Innovation and Entrepreneurship Program at the US National Academy of Science, and now teaches global innovation policy at Georgetown University. He is also a non-resident senior adviser to the Renewing American Innovation project at the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies.

More in this series:

- Viewpoint: Standards, not protectionism, will make the EU stronger in technology, MEP argues

- Viewpoint: The EU’s strategic autonomy prescription is the wrong medicine

- Viewpoint: Are we heading towards scientific self-censorship?

- Viewpoint: Companies, not governments, should lead global tech collaboration

- Viewpoint: Make sure that openness remains in EU research and development policy

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.