With hopes of association fading, London has set out an agenda for a domestic alternative. But a new prime minister could threaten money promised for research

Boris Jonhson, outgoing Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. Photo: Tim Hammond / No10 Downing Street

The UK has released long-awaited details of its ‘Plan B’ alternative to Horizon Europe, including a rival to the European Research Council (ERC) and continued support for its researchers to join Horizon consortia.

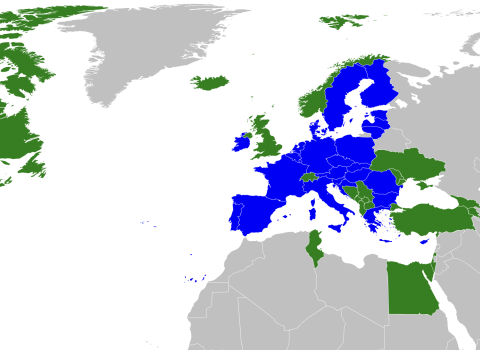

London still says it wants to associate to Horizon Europe, but with the Commission blocking this until frictions over the Northern Ireland Protocol are resolved, the UK has set out how it will respond if the government runs out of patience and pulls the plug on association.

“The de facto situation is that we are not associating to Horizon and we are already feeling the effects,” said Ben Johnson, executive head of strategic research and innovation development at the University of Strathclyde, and a former adviser to several UK science ministers. “This document offers clear measures to protect and stabilise the system for the next few years,” he said.

The UK’s plan is divided into two parts. The first are “transition measures”, designed to steady the ship if the UK decides to give up waiting on association, but before it launches a fully-fledged alternative.

The most significant pledge is a promise to fund all UK participants in Horizon Europe consortia where grant agreements are signed before 31 March 2025.

Even if the UK isn’t associated to Horizon Europe, UK researchers can still join these consortia if they bring their own money, although they can’t coordinate them. So this should enable UK researchers to join around two thirds of Horizon calls, even if association doesn’t happen.

This pledge to fund all consortia represents a win for universities, which were worried that the government would restrict funding to particular topics, or impose extra screening on gets money.

“I think it’s important that it’s broad and it’s until 2025,” said Catherine Guinard, policy and advocacy manager at the Wellcome Trust, which is the largest charitable funder of research in the UK. “If it had been restricted thematically […] it would be really worrying for the UK and the EU.”

Steady the ship

In addition, the UK will plough money into a range of other existing schemes to cushion the blow of not associating to Horizon Europe.

There will be more money for various fellowship schemes run by national academies and other research funding bodies.

Extra cash will flow to various innovation programmes, including the global Eureka network, to help UK businesses maintain existing links with European partners “while forging stronger partnerships with countries further afield, such as South Korea, Canada, and Singapore.”

There will also be a “talent and research stabilisation fund” to prop up the income of universities that are particularly badly hit by the loss of Horizon Europe money.

The UK will continue to guarantee funding for successful UK applicants to Horizon Europe who can’t access money because association isn’t agreed.

“What we really hope is that’s going to give reassurances to keep researchers engaging with the Horizon Europe programme, and they will be funded one way or the other,” said Jo Burton, a policy manager at the Russell Group of research intensive universities.

What’s more, London has pledged to look at “in-flight” applications to Horizon Europe. These are applications to mono-beneficiary schemes, like ERC or European Innovation Council grants, which end up not being evaluated because the UK pulls out of association.

Instead, they will be re-submitted and evaluated by UK Research and Innovation, and funded if deemed good enough, although there are no details yet on how this will be done. “It’s good to see that, but it’s not going to compare with what an ERC grant means,” said Guinard.

Long-term alternative

These transition measures are designed as a bridge to the creation of a full UK alternative to Horizon Europe. However, it is unclear how long this will take.

As expected, it will include what will effectively be a UK version of the ERC. “Our bold UK fellowship and award programme will embrace the success of the ERC and MSCA, providing the same career benefits and prestige with enhanced funding and flexibilities to retain and attract top talent in the UK,” the plan says.

In addition, there will support for global collaborations between researchers, including continued funding for UK researchers to join Horizon Europe consortia as third country participants.

While all consortia will be backed until 2025 under the transition measures, it’s possible that this guarantee could become more limited, or subject to a UK specific test after that. “There’s a question about the longer term,” said Vivienne Stern, director of Universities UK International (UUK). “We have to prove that this is worthwhile.”

The UK’s longer-term plan foresees more money for industrial research and innovation, plus funding for new research infrastructure and digital research capacities. The plan is to steer this funding away from the dominant ‘Golden Triangle’ of universities in Oxford, Cambridge and London to achieve more balanced R&D activity across the country.

More details on these long-term plans will be released in the autumn.

No guarantees

However, despite these latest plans, a change of prime minister in the UK could throw everything into doubt.

Last year, a multi-year spending review set aside £6.9 billion for Horizon association or an alternative until 2025, reassuring universities that they would receive funding either way.

But the fall of prime minister Boris Johnson has UK researchers concerned that his successor could raid this pot of money to fund other priorities.

“That is a concern,” said Burton. “There is a lot of a fiscal pressure.”

“Nothing is guaranteed,” agreed Stern. “We shall see.”

UUK has written to the final two leadership contenders, foreign secretary Liz Truss and former chancellor Rishi Sunak, urging them to make research and innovation a priority. One cause for hope is that they were both in the Boris Johnson cabinet that agreed to fund Horizon Europe association, Stern pointed out.

However, science and research has barely figured in the leadership contest so far, eclipsed by other topics including tax cuts.

Truss, the favourite, has already pledged an emergency budget to cut taxes. She is also behind legislation to override the Northern Ireland Protocol, which has deepened distrust in Brussels.

Conversative Party members are voting until September to decide which of Truss or Sunak becomes the next prime minister.

Last gasp

Even though hopes for Horizon association are dwindling, the UK government and research heads point out the Commission could at a stroke solve the issue by dropping its objection to UK association, setting aside broader political strife.

In a letter today, the Russell Group chief executive Tim Bradshaw wrote to Commission president Ursula von der Leyen that not confirming UK association would be a mistake.

“Without the UK’s full association, the programme will become less competitive, with knock-on impacts for the excellence and prestige of EU grants,” he writes. “Association is therefore too important to be used as part of a negotiation and the current impasse shows this is having no leverage over the Northern Ireland protocol.”

“The door is shutting. We can’t be in limbo forever. [But] there is the last gasp opportunity for the European Commission,” said Stern.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.