Researchers are hopeful about the impact of Horizon Europe on the EU research landscape but criticise the paperwork, according to a Science|Business survey

As with a new movie or play, the reviews are starting to come in on the EU’s big new research programme, Horizon Europe. And the verdict is “so-so”, according to an online survey by Science|Business.

Most people familiar with the programme praise its objectives and favourably compare it to the EU’s last R&D programme, but they complain about continuing problems with bureaucracy and paperwork.

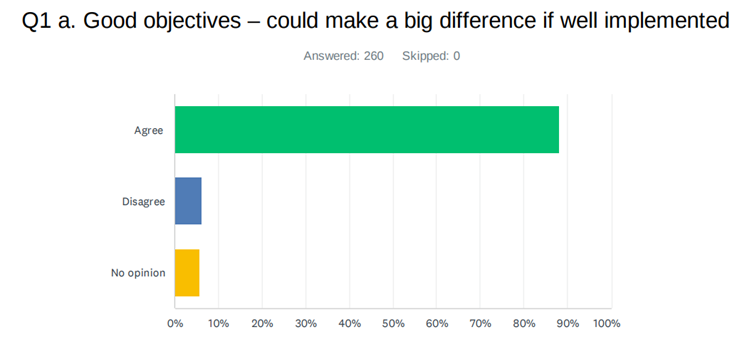

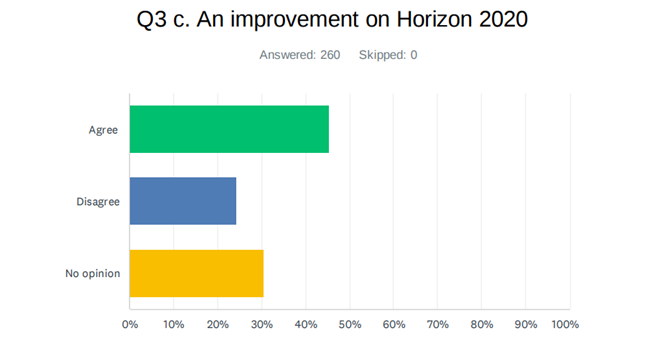

Of the 260 people who filled out the online survey, 88% say they like the objectives of Horizon Europe, which include helping to meet the challenges of climate change, healthcare in a pandemic, and European technology competitiveness. Overall, nearly half – 45% - said the programme is generally an improvement on its predecessor, Horizon 2020, while 24% disagree, and the rest don’t yet have an opinion on this point.

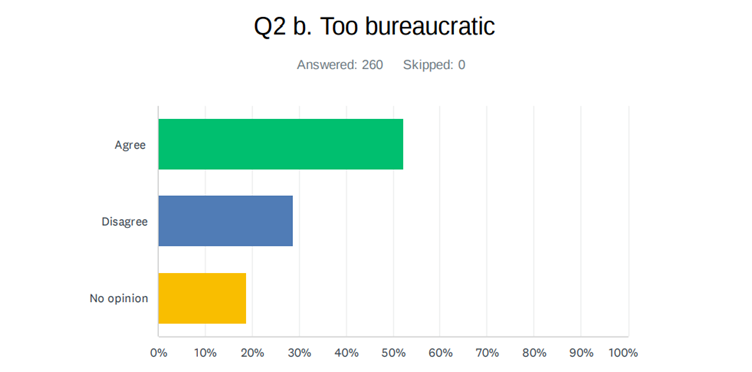

But when people start talking about the details of applying, getting evaluated and contracting, the mood darkens. In all, 52% believe the application process is too bureaucratic, 70% say the odds of winning are too low, and 38% say the programme won’t do enough to involve east European R&D players.

And there’s a frequent recommendation to the Commission, to provide more guidance to applicants about how to fill out all the forms.

The long-awaited Horizon Europe programme officially launched in February 2020, but it took the Commission a few more months to get the calls for grant applications off the ground. It was a shaky start, with key parts of the puzzle coming in late, such as the annotated grant agreement which break downs the legal details of Horizon Europe contracts.

Once the applications started flowing, many researchers complained the submissions platform was having numerous technical glitches and of the difficulty of fitting all the science, impact and administrative requirements into the new 45-page proposal limit, among other issues.

Science|Business is collecting feedback on Horizon Europe from around the research world, and it will air all the results at its annual conference, online 8-9 February. This survey was conducted online in December and January, gathering views of researchers and staff at universities, companies, research institutions, consultancies, associations and government bodies across Europe. In all, 70% of respondents have actually gone through the application process.

The survey is intended to provide a snapshot of individual concerns or opinions, rather than a statistically significant sampling. It will be supplemented by feedback in a series of Science|Business workshops over the past winter with its network of more than 70 universities, companies and public-sector organisations.

Not so easy

The survey results echo many of the concerns raised publicly from 2018 to 2021, when European legislators and member states were arguing over the legislation for the programme.

For instance, too bureaucratic and difficult to apply to – this has been one of the biggest criticisms faced by EU research programmes over the last three decades.

With each new rendition of the seven-year R&D programmes, the Commission has promised simplification. This time around is no different, although there are limits to how far the Commission can go, given it is handing out public funds. “Applying for high-value grants for collaborative research in a multinational programme will always entail a significant degree of form-filling,” a Commission spokesman told Science|Business last month.

About half of the 172 surveyed researchers who had already applied for grants reported the Horizon Europe application is ‘about right’ when it comes to difficulty. Another 41% said it was hard. Only 3.5% were brave enough to call it easy. 83% of these respondents who have applied for Horizon Europe grants were specifically involved with the collaborative research projects of Horizon’s Europe’s biggest section, so-called Pillar 2 – so these comments don’t necessarily reflect on other parts of the programme.

Compared with Horizon 2020, 46% of the experienced applicants said the difficulty of the Horizon Europe forms was about the same, 35% reported it being harder and 11% said it was easier.

In the end, whether it’s easier or not, many researchers have said those who feel the burden of the paperwork-heavy application process are more likely to be first time applicants and less experienced researchers. A long applications process deters unseasoned applicants and threatens to make Horizon Europe an exclusive club for big research players. Many do not dare apply without the help of professional proposal writers.

“We had so much interest in the calls,” one representative of an EU grants office for a university wrote in a survey response. “But as soon as they see the proposal template with "Open Science", Data [Management] Plan, [do no significant harm principles], Impact table etc., they all decide not to apply. It is a shame. Only consultancies are prepared to do that work as it is impossible for a scientist, even with support from an experienced EU Office, to prepare a proposal.”

Mixed feelings on the application process

In social media and online conferences, one frequent cause for complaint is about the Commission setting a shorter page limit for most applications, of 45 pages instead of 75 in Horizon 2020. The argument is that with bigger research consortia and more-demanding assessments, it’s too hard to distil the genius of an application in 45 pages.

In the survey, 33% of people who had made an application to Horizon Europe echoed that point.

But the majority, 55%, said the page length was about right. And some respondents complained about those complaining. “Reduced page limit is great - those complaining are bad writers,” one person said.

Some welcomed the new page limit, but said the Commission is requiring too much of the application be devoted to the administrative details rather than the core research proposal. “Data management, open science and the impact sections are too long. This does not leave enough space for the description of the actual project,” said one respondent.

More than a quarter of respondents - 27% - said the instructions aren’t clear enough. But 64% said they are OK. And among those who added write-in responses to the survey, some suggested that while they had no trouble with the instructions they still struggled to understand how the applications can tick off all the boxes, from proving a project qualifies as environmentally sustainable to assuring the evaluators of its sound open data management.

“Even though the instructions are clear enough, it remains challenging to structure an application that would sufficiently tackle the EU horizontal principles. Further guidance would be highly appreciated,” a respondent wrote.

One person even looked to the US for a better model, comparing the Commission’s 45-page proposal to that of an application for a grant from the US National Institutes of Health, where the research strategy can take up to 12 pages and one page is dedicated to project aims.

Left behind

One common criticism of the EU research programmes is their continued failure to get new organisations from eastern and central Europe, and researchers from non-EU countries involved.

This time around is no different, as there appears to be a lot of confusion over third country participation. The Swiss, whose continued participation in the programme on equal footing with EU member states fell victim to political disputes, are especially struggling to make sense of the new terms of their involvement in the programme.

Respondents wrote in asking the Commission for clearer – and more quickly delivered – information on third country participation in specific programmes and calls.

“For us based in Switzerland, our lives have become very complicated administratively. We also feel like belonging to a kind of second zone partners with very low visibility,” one person wrote.

Others highlighted the need for guidance on how to write a better application, especially for researchers who are not based in those EU countries that have typically won the larger share of grants.

“Instructions are clear, but there is a lack of information about how to write a competitive application. This know-how is available in the west which can rely on a large number of successful applications, while it is much harder to access such know-how in central and eastern European countries thus leading to unequal access to all the information that would be necessary for successful applications,” someone wrote.

In the end, simplifying the programme and giving clear guidance is about equal opportunities for all. “To simplify application processes is key to give fair opportunities to everyone,” one person concluded.

Editor’s note: Full results of the survey will be published online at the annual Science|Business Network conference 8-9 February.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.