Details of the terms on which Israel, UK and Switzerland can join quantum and space projects are now public. But it’s not a done deal for the Commission which says negotiations are ‘ongoing’

Thomas Rachel, parliamentary state secretary to Germany’s minister for education and research. Photo: Federal Ministry of Education and Research

Member states say a newly found consensus on third country access to sensitive research projects means the European Commission should now go ahead and publish the Horizon Europe work programme detailing calls for proposals, deadlines and budgets for the next two years.

“I am pleased to note that the EU Member States and the European Commission have reached a well-balanced compromise which provides a clear signal for excellence and openness in international cooperation with major strategic partners,” said Thomas Rachel, parliamentary state secretary to Germany’s minister for education and research.

Last week, member states and the Commission reached an agreement under which researchers from Israel, Switzerland, Britain and other non-EU countries may be allowed to join the EU’s quantum and space research projects.

Stakeholders hope the agreement will end months of uncertainties around international participation in sensitive R&D projects in Horizon Europe, the €95.5 billion R&D programme. The agreement also paves the way for the full launch of the programme next week, nearly six months after it was due to get underway.

But some are not rushing to draw the same conclusions from the negotiations last week.

The Commission has yet to confirm the agreement. In a statement emailed to Science|Business on Friday, a spokeswoman said the Commission would not comment on “ongoing” negotiations.

France, one of the very few member states that was in favour of the restrictions did not want to comment either. A government spokesman told Science|Business that France will wait for the official reply of the Commission before making any statements on the agreement.

EU Commissioner for the internal market Thierry Breton, is one of the main proponents of greater restrictions on international cooperation in research projects. Breton, a former finance minister and CEO of a number of French multinationals, wants the EU to be able to protect its investments in cutting edge technologies from potential leaks to global competitors.

On the other side of the argument, Germany has gathered a sufficient majority among member states to derail a proposal introduced by the Commission in March, which was supported by France and a handful of other member states.

“We are delighted that the consensus achieved now enables the publication of a wide range of calls for proposals under Horizon Europe,” said Rachel.

According to the agreement, eligibility to participate in 21 sensitive research calls could be extended to include legal entities established in associated countries which provide necessary assurances concerning protection of the EU’s strategic assets, interests, autonomy or security.

“We agreed on a clear process with the European Commission which involves the EU member states in the development of fair criteria for association agreements, for example regarding intellectual property,” said Rachel.

Over the few next months, countries including Israel, Switzerland and the UK, that are seeking associate status in Horizon Europe, will have to negotiate terms with the Commission.

“It is up to the candidate associated countries to fulfil these criteria and to negotiate association agreements with the Commission as soon as possible,” Rachel said.

Swiss researchers see the agreement as a step forward towards gaining associated status in Horizon. “If confirmed this is excellent news for the future of Swiss and European research,” said Joël Mesot, president of ETH Zurich.

Despite being associated in previous R&D programmes, Switzerland has to renegotiate its status in the middle of a bilateral political fight over its relationships with the EU as a whole. Last month, it ended seven years of talks on consolidating a series of sector-specific deals into one overarching agreement with the EU. The Commission is now assessing whether that will also impact science relations and association negotiations.

UK government officials say, if confirmed, the outcome of the negotiations is good news for British researchers. But the Commission has to make it clearer what the criteria the UK has to meet in order to be able to join research consortia in quantum calls.

Necessary conditions

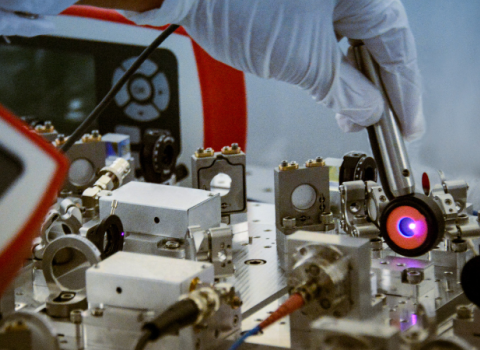

In future, associated countries will have to provide the Commission guarantees that private companies involved in quantum collaborative projects and holding sensitive intellectual property will not be taken over by other countries.

Associated countries would have to demonstrate they would provide the same level of protection as member state could. All Horizon applicants will be prevented from exporting IP outside EU member states and associated countries.

Calls that are part of part of the EU space programme, Copernicus and Galileo are only open to member states.

The UK and Switzerland are very active in the quantum flagship project in Horizon 2020, the predecessor of Horizon Europe. Researchers had begun to worry what would happen if those collaborations, with stakeholders warning that severing ties with close partners could translate into delays in achieving the EU’s goal of becoming more competitive in these very technologies.

Officials say the Commission has provided arguments for why associated countries should be excluded from sensitive projects, but has not provided evidence about the impact of cutting off scientific ties with long standing partners.

In addition, the idea of limiting access to sensitive projects was put forward very late in the implementation negotiations between member states and the Commission.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.