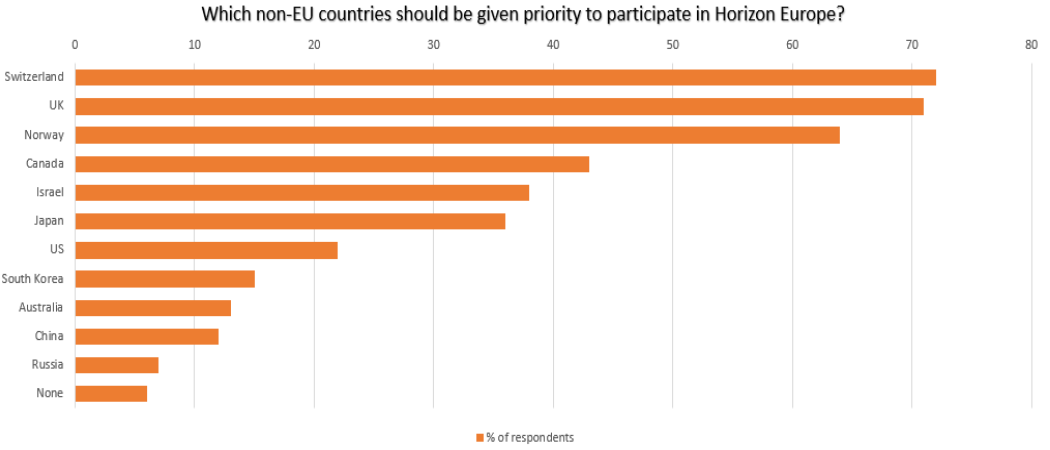

Readers rank non-EU countries by how much they want them as partners in the next EU research programme, Horizon Europe

Source: Science|Business online survey 18 Aug. – 24 Sept., 502 respondents.

If the EU’s Horizon Europe programme were a popularity contest, the winners for most-desirable research partners would be Switzerland, UK, Norway and Canada, according to a survey by Science|Business.

Of 502 respondents to an online survey from 18 August to 24 September, 72 per cent said Switzerland should continue as a formal non-EU partner in the next R&D programme, Horizon Europe, starting 1 January. Nearly as many, 71 per cent, said the UK should stay in the programme, despite its Brexit from the EU overall. Norway, already a Horizon partner, came third in the rankings at 64 per cent, while Canada topped the list of countries that could become new Horizon members, at 43 per cent.

For years, the EU has allowed select non-EU countries to join in its research projects; at present, there are 16 such “associate” members, including Switzerland, Norway and Israel (38 per cent back its continued participation, not exactly a ringing endorsement.) So that their scientists can apply for grants on an equal footing with EU researchers, these countries contribute cash to the central EU pot based on a somewhat messy formula taking into account the size of their economies.

For Horizon Europe, the European Commission is proposing to change the formula and expand the partner list to include some more rich, scientifically powerful countries – such as Canada, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. The rationale: working with other science powers would benefit the EU, as well as the world.

Yet the politics of this have proven messy. Because of Brexit and budget battles, the commission has stalled any serious negotiations with non-EU members for months. Some EU members – particularly in Eastern Europe – worry the newcomers could take grants away from their own researchers. And the terms of membership are still vague, with the commission so far saying only that there should be a fair balance of money in for money out, but no explanation yet for how that would work. That ambiguity, dating to 2018, has started to give some potential new entrants cold feet.

All this uncertainty is reflected in the comments from survey participants, who are all Science|Business readers offering their anonymous views. One commented that any deals with non-EU countries, including the UK, should be allowed “only if they contribute – and allow us to participate in their (own national) calls” for grant applications. Another wrote that eligible partners are “those countries who contribute financially AND share EU values and principles, excluding security-related calls.”

Others see it in more geopolitical terms. “Partners are needed to form a third world science centre competitive with the US and China,” wrote one respondent. In the survey, just 22 per cent said the US should be allowed to join, and 12 per cent that China should. In fact, US officials have indicated they aren’t likely to try to join. China has been pushing to join Horizon projects with its own money, but the draft Horizon legislation bars countries that don’t share the EU’s “democratic” values. As for Russia, just 7 per cent thought it should be allowed to join.

See more results from the survey:

Multinationals not quite so welcome in the EU’s Horizon R&D programme

Survey results: EU should boost Horizon R&D spending, but also simplify

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.