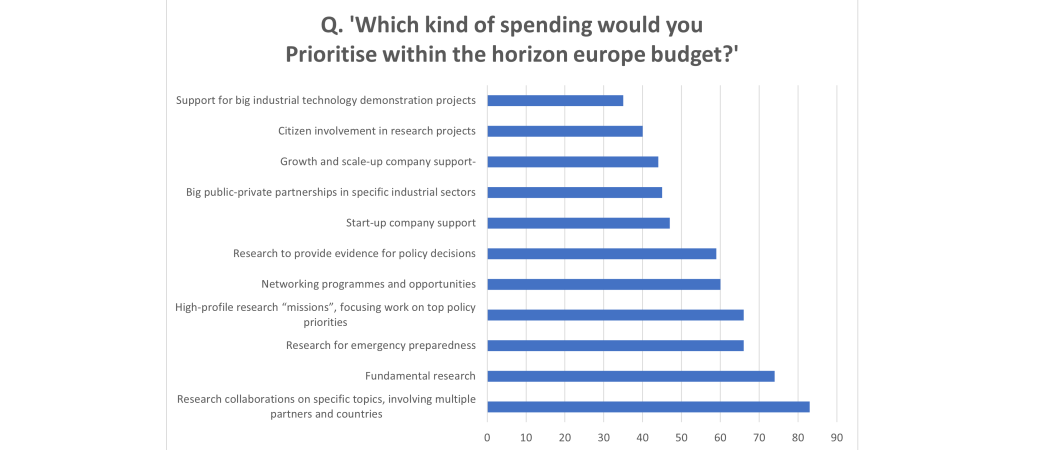

Science|Business survey finds limited support for the EU funding big company R&D. Citizen science is also not that popular

Source: Science|Business online survey 18 Aug. – 24 Sept., 502 respondents.

Funding basic and applied research is all well and good – but the idea of the European Commission supporting big industry R&D is a lot more controversial among people familiar with EU research programmes, according to a survey by Science|Business.

Among 502 respondents to an online survey from 18 August to 24 September, the core of EU R&D programmes is very popular – with 83 per cent saying they support Horizon 2020’s classic multi-partner, multi-country applied research projects, and 74 per cent saying they support fundamental research.

But when it comes to industrial research, the verdict splits. “Big industrial technology demonstration projects” – which often involve multinationals – are backed by only 35 per cent (and a third of those “strongly” agree.) By contrast, 36 per cent said they oppose that kind of funding. Likewise, “big public-private partnerships” – again, a frequent multinational zone – split with 45 percent for them, 26 per cent against, and the remainder uncommitted.

“Stop giving money to large and private industry,” wrote one anonymous respondent to the survey. “Private partners don’t need the money to innovate since they do this from their own R&D budgets.”

The debate over public versus private EU funding has been heating up in recent years. The EU programmes began in 1982 as a deliberate piece of industrial policy, to help Europe’s tech industry compete better against then-dominant American and Asian (at that time, Japanese) companies. But since then, funding for public research has soared – with, for instance, the creation in 2007 of the European Research Council for frontier science, and rapid growth of collaborative research projects to tackle climate change, healthcare or social problems.

Currently, about a third of the EU money goes to private companies – and the bulk of that is to small firms. Several multinationals participate without getting EU cash; instead, they join formal partnerships to which they contribute in-kind services (researcher time and lab facilities). But, critics note, in return they get to exploit technologies developed in these publicly funded partnerships – and have a strong voice in shaping which technologies get developed and which don’t.

One surprise in the survey, however, was the equally wobbly position of research directly involving citizens – so-called citizen science projects. Of the survey respondents, just 39 per cent support such projects while 27 per cent oppose them; the rest are uncommitted.

This type of project has grown quickly, on the notion that the EU should involve normal folk in the projects as a democratic exercise, and to promote science education. For instance, the German government as current president of the EU Council is promoting a citizen science project called “plastic pirates”. The aim is to recruit thousands of teenagers to monitor and measure plastic pollution in their local rivers and lakes, and feed the results into a scientific database.

On the EU programme objectives, the survey suggested that most people buy the commission’s official rationale for what it does. For instance, 83 per cent said they support the idea of using EU R&D programmes to promote ethical research behaviour, and 82 per cent support cross-border collaboration – especially between rich and poor countries. The weakest support was for promoting entrepreneurship, with 65 per cent in favour.

And as for applied versus basic research, one respondent offered this conclusion: “The eternal battle for funding between fundamental and applied research – a balanced portfolio of BOTH is needed! One does not exclude the other.”

Coming next week: Who should play? Who should benefit?

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.