Experts from the region point to a lack of national research funding, poor access to networking and cultural factors as reasons for the low success rate

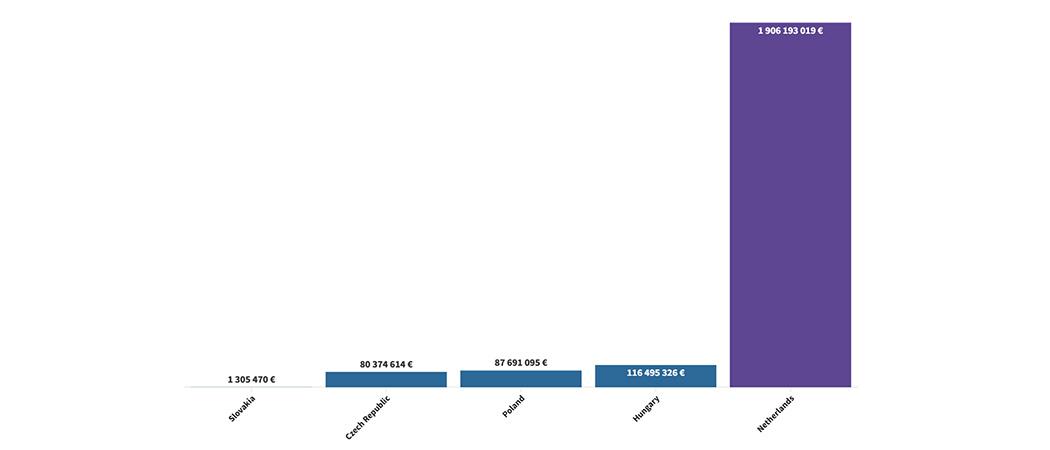

According to ERC data the total combined amount of ERC funding that researchers based in the Visegrad group of Hungary, Poland, Czech Republic and Slovakia have received since the scheme was launched in 2007 is around 6.6 times lower than researchers based in the Netherlands alone have received.

Key members of central and eastern Europe’s science academies and institutes say more must be done to improve the region’s success rate in winning European Research Council (ERC) grants that are awarded as part of Horizon Europe, the EU’s key funding programme for research and innovation.

Fewer than 8% of applicants in central and eastern Europe were awarded ERC grants between 2007 and 2021, compared to between 15% - 16% of applicants in the Netherlands, Germany and France.

The total combined amount of ERC funding that researchers based in the Visegrad group of Hungary, Poland, Czech Republic and Slovakia have received since the scheme was launched in 2007 is around 6.6 times lower than researchers based in the Netherlands alone have received, ERC data show.

Gergely Bőhm, head of the president's office at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and national contact point for the ERC in Hungary, said this is not a new issue. “Since the framework programmes began in the EU for research, this has been a problem,” he said.

ERC gives out grants solely on the grounds of excellence, meaning researchers in countries with low research and innovation performance are less likely to get the prestigious awards. “Certain countries are catching up a little bit, but still the difference is huge,” said Bőhm.

Academics dismiss the idea that the ERC is biased against researchers from central and eastern Europe, pointing instead to low national R&D investment levels and poor institutional support as the main reasons for the performance gap.

All four Visegrad countries allocate less than the EU average of 2.3% of GDP to research and development, figures from 2020 show. The Czech Republic puts 2% of GDP into R&D, an increase of 0.7 percentage points from 2010. Hungary is second at 1.6%, followed by Poland at 1.4%, and Slovakia 0.9%.

Poland has increased its expenditure on R&D by 0.7 percentage points in the past 10 years but Paweł Rowiński, vice president of the Polish Academy of Sciences, says this is not enough. “I would definitely say that the amount spent on research is too low in our countries,” he said.

Funding is limited and it is also spread too thinly, so all research groups get some money. “We need to focus on funding the very best projects, on making sure they get the money they need,” Rowiński said.

The Polish Academy of Sciences has established an excellence in science department, which is dedicated to helping top researchers prepare ERC applications. In 2021, ten researchers in Poland were awarded ERC starting grants, a huge increase on previous years when no more than two – and some cases none - were successful.

While Rowiński says it’s unclear if the excellence in science department should take all the credit for the improvement most researchers who got to the second stage of the grant application process received some support from it.

The number of successful ERC starting grants in each country between 2007 and 2021.

Too few submissions

Across the border in Slovakia, researchers do not submit enough ERC applications, said Martin Venhart, first vice president of the Slovak Academy of Sciences and formerly Slovakia’s national delegate for the ERC. “This is the first problem,” Venhart said.

Only one Slovakian researcher, Jan Tkač, has ever been successful in obtaining ERC funding. He first received a starting grant in 2013, followed by a proof of concept grant in 2018. According to Venhart, Slovakia needs a system to help researchers write their proposals and submit them, because many get discouraged during the process and give up on the idea completely.

Another problem is that researchers are not trained to explain their proposals concisely, within the five-page limit of an ERC application, even if they have an excellent idea with lots of potential. “Usually, people go too deeply into the details and don’t get exactly to the point,” said Venhart.

Bőhm, Rowiński and Venhart agree a more fundamental barrier to success is that researchers in central and eastern Europe lack experience in conducting independent research. Young researchers stay too connected to their PhD supervisors and hesitate to gain independent experience abroad.

“I personally fired the best PhD students that I had, and they had to do their postdoc abroad,” said Venhart. “Maybe they will come back, maybe not. It's not very good for us, but it's very good for them.”

Momentum in Hungary

In Venhart’s view, Slovakia could fix these issues if it replicated the Momentum (Lendület) grant scheme set up by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in 2009. It was originally introduced to attract Hungarian researchers working abroad back to establish their own research groups, or to keep the top Hungarian scientists at home. But the grant ended up doing more than that.

“It turned out that it helped ERC applications immensely as well,” Bőhm said. Researchers who won Momentum grants had proof that they can lead research groups and handle bigger grants from the ERC. “Three out of our three ERC consolidator grant winners in 2021 were Momentum grantees, and in general the correlation is massive,” Bőhm said.

The Slovak Academy of Sciences has set up a similar system on a smaller scale and this is proving successful. Three Slovak researchers have made it to round two of the ERC starting grant process this year.

However, Venhart says the scheme needs further government financial support. “If they fund 30 scientists each year, then I'm sure that within five or 10 years, the situation will be significantly different,” he said.

Networking

István Szabó, vice president for science and international affairs at Hungary’s research, development and innovation office said research institutes in central and eastern Europe need to build better international networks.

Universities and research institutes in western Europe are very well connected and collaborate regularly, while those in eastern Europe are left out of the loop.

“Connections between research institutes are usually built up on a peer-to-peer basis,” said Szabó. “Hungarian research institute will have far fewer opportunities to connect with a German research institute without someone knowing someone there in person.”

Such collaborations may be hindered by the simple fact that western scientists are less likely to want to conduct research in eastern European countries with less renown.

The ELI-ALPS Research Institute in Szeged, Hungary, which opened its doors in 2021, is the first pan-European research infrastructure to be built in the newer EU member states of central and eastern Europe. It houses one the world’s most advanced high-power laser infrastructures but is struggling to attract researchers from western Europe. “It's a top-class research infrastructure,” Szabó said. “But for some reason this doesn't seem to be attractive enough.”

ERC is aware of the problem

The ERC performance gap was debated earlier this year at a meeting of the science academies in the Visegrad countries. Philippe Cupers, head of the life science unit at the ERC executive agency, acknowledged the scale of the problem. “Of course, we know that 50% of ERC grants go to the 40 or 50 top research institutions” he said.

Cupers encouraged more researchers to take part in the ERC’s visiting fellowship programme and the mentoring initiative to increase their chances of winning an ERC grant.

The fellowship programme allows potential ERC candidates to spend up to six months with successful ERC candidates to gain experience, while the mentoring programme helps candidates prepare for the ERC application process.

Optimism for the future

Tomáš Slanina, an ERC starting grant winner who leads a research group at the Institute of Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry in the Czech Republic, says that success comes with experience. His first application for an ERC grant in 2018 was refused but he tried again in 2021 and succeeded.

“I had a better CV and some preliminary data that we already worked on,” Slanina said. “But that was not as important as the way I set the final research goal the second time round, how I shaped the project and how much I worked on it.”

For Slanina, the ERC evaluation process was fair. The reason researchers based in Visegrad countries are not as successful as their western counterparts is rooted elsewhere. “The ERC is about big ideas and high-risk projects where there is no certainty about the results,” he said.

Researchers are used to national schemes, where they play it safe, to make sure that they do not overpromise what they can deliver. “We have to completely change the way we think about the research project, and we have to be brave,” said Slanina.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.