Since COVID-19, EU leaders are pushing for greater independence from US and Chinese technology. But what would that mean? Science|Business begins a series of special reports and events

The EU’s Maroš Šefčovič (L) and Thierry Breton (R) are two of the main faces behind the bloc’s new assertive push

What is ‘tech sovereignty’?Science|Business is launching a year-long series of special reports, events and white papers defining and analysing this important policy trend. Join us Sept. 8 for the kick-off event: Industrial R&D: Europe First? Want to work with us in the months ahead: Your organisation can join our Technological Sovereignty study group.

|

As political memes go, “tech sovereignty” has become a viral phenomenon among European leaders in the past six months. Since the COVID-19 crisis started, politicians across the left-right spectrum have started pushing to reduce Europe’s dependence on US or Chinese-origin technologies. From vaccine development to artificial intelligence, billions of euros are now being mobilised across the European Union; and the rhetoric has gone nuclear.

“If we don’t build our own champions in all areas — digital, artificial intelligence,” French President Emmanuel Macron recently said, “our choices will be dictated by others.”

One question, first: What is technology sovereignty, anyway? The answer depends on who you ask. There are many agendas around this label, which is applied in dramatically different ways. And it’s not even one label – it’s interchangeable with several similar terms that have also developed great political traction over the past year. There is “strategic autonomy”, “regulatory sovereignty” and, increasingly, “digital sovereignty”.

The scaled-up rhetoric speaks to a growing recognition that Europe must compete better in key areas, put an urgent focus on security of imports of vital goods, and limit the reach of US and Chinese technology. This aspiration has grown during the COVID-19 pandemic, which cruelly laid bare the fragility of international supply chains.

In her November 2019 inauguration speech, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen set technology—along with climate change—as the EU’s top priority for the next five years. Von der Leyen said the bloc “must have mastery and ownership of key technologies in Europe,” including quantum computing, artificial intelligence, blockchain, and chip technologies.

Thierry Breton, the EU’s internal market commissioner whom many regard as the key animating force behind these ideas, this week told Politico that Europe needs “to be more self-sufficient, to be more independent, autonomous. Some say sovereign. We need to identify our own resources. We have some very good partners but we are dependent in some areas.”

The EU political elite argue that tech sovereignty is also about protecting “European culture and values”. Officials talk about “human-centered” autonomy, with which individual citizens are personally sovereign over their own data and interactions with AI.

But hidden underneath all this rhetoric, some fear, is a new protectionist zeal. Alexandre Affre of the BusinessEurope industry association says, “The common understanding [of tech sovereignty] needs to be improved. There are merits in discussing this further, but there are fears as well that the concept could be misused for unilateral, protectionist approaches.”

‘Don’t be a sucker’

It wasn’t so long ago that there was a very different message coming out of Brussels. Former Research Commissioner Carlos Moedas, who was replaced by Mariya Gabriel last year, memorably called for EU research programmes to be “open to the world”.

This mantra hasn’t aged particularly well. The message has shifted – access to the next EU research programme will only be extended to countries that respect that openness themselves. This shift can be seen in the larger, evolving EU approach to all things digital and technological, where the new mantra may as well be: Don’t be a sucker.

An arms-open approach, as well as a narrow focus on fundamental rights and market regulations, is “naïve,” says Breton, who is the former CEO of the French tech firm Atos. His is a hard-headed take on the world - one that concedes that Europe missed the boat on building giant internet platforms, and now has to search elsewhere to find its niches.

“We missed the first wave on personal data,” Breton said this week. “It’s not rocket science to build a platform but you need a large market. Facebook, Twitter, Baidu all have a large market. We have one too but there’s barriers, and [different] language[s].”

The shape of things to come

Whatever the motivations behind Europe’s sovereignty push, the gearshift is visible in several mega-political projects.

Gaia-X, launched last year by leaders in Paris and Berlin to create a ‘federated’ computing network with specific European security standards, is regarded by some as the most concrete manifestation of European tech sovereignty.

It was conceived as a way to resist the dominant position of US cloud service providers, such as Amazon, Microsoft and Google, by agreeing on open technical standards, permitting customers to switch easily away from the Americans. The underlying concern is the lack of control; the fear of being ‘locked out’ of US-based cloud systems, as America takes its own turn toward nationalism under Donald Trump. The EU-wide effort is a so-called Important Project of Common European Interest (IPCEI), a relatively new kind of legal creature in the EU that gives companies an exemption from competition rules to work together, with their governments’ support, on strategic projects.

If Brussels has conceded the battle on building GAFA-equivalents using mountains of personal data, the “big fight” for industrial data is still there to be won, Breton has said. He is pledging investment in components, processors and microprocessors, chips and sensors, which are at the start of many strategic value chains such as connected cars, phones, Internet of Things, high performance computers, and edge computers.

“We must invest massively, with the objective to produce in Europe high performance processors and reach 20 per cent of the world capacity in value,” said Breton. Today, Europe accounts for less than 10 per cent of global production.

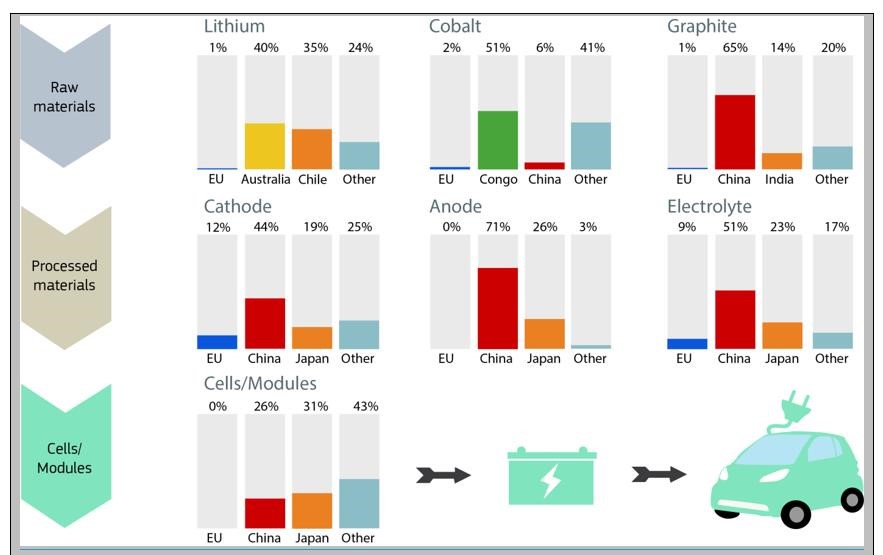

Another big EU tech sovereignty mission is in batteries, including financing raw-materials extraction and processing, under the umbrella of the European Battery Alliance. The partnership, another IPCEI, sees public money go directly into the hands of large private companies, although some of the profits from the investments will be reclaimed for public coffers.

According to a 2014 Commission report, Asian companies have an 88 per cent share of global lithium ion manufacturing capacity, with more than 50 per cent in China alone. If Europe doesn’t master battery technology, then there won’t be a car industry in Europe, tech experts say. There is deep concern that Germany is missing its moment on autonomous driving and electric vehicles – foreign batteries can account for about half the cost of an electric car – and the country’s big auto companies are losing market share.

The European Investment Bank aims to increase backing for battery projects to more than €1 billion in 2020. That will match in one year what it has offered the sector over the last decade. At stake is control over a new kind of data. Modern vehicles generate around 25 gigabytes every hour. Autonomous cars will generate terabytes of data that can be used for new services and for repair and maintenance, Breton has said.

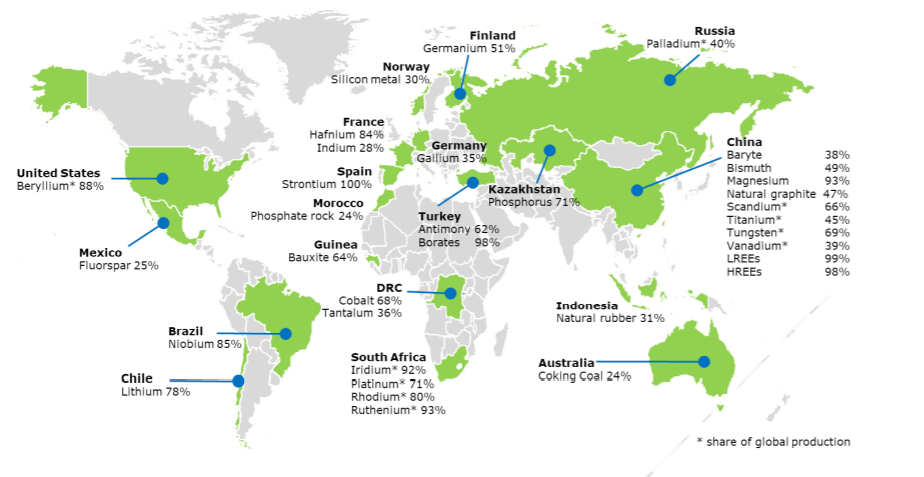

A further industry-led group, the European Raw Materials Alliance, was announced in Brussels on 3 September, to build supply chains around metals and rare earths – elements used to make batteries and renewable energy equipment. Again, Beijing dominance is the focus: as much as 93 per cent of the EU’s magnesium comes from China, according to the Commission. Commission Vice President Maroš Šefčovič, in announcing the alliance, said: "A secure and sustainable supply of raw materials is a prerequisite for a resilient economy. For e-car batteries and energy storage alone, Europe will for instance need up to 18 times more lithium by 2030 and up to 60 times more by 2050. As our foresight shows, we cannot allow to replace current reliance on fossil fuels with dependency on critical raw materials. This has been magnified by the coronavirus disruptions in our strategic value chains."

Strong Berlin-Paris tandem

The eurozone’s two leading economies, France and Germany, have thrown their considerable political heft behind this more assertive digital and industrial approach.

A strong emphasis on sovereignty is the most striking feature of the German plan for its six-month presidency of the Council of the EU, which runs until the end of the year. In the European Parliament in July, German Chancellor Angela Merkel further highlighted this point, saying, “It is very important that Europe enjoys technological sovereignty, particularly in key areas such as artificial intelligence and quantum computing, also in securing a secure, trustworthy data infrastructure.”

With the big American tech platforms moving rapidly into the space of AI, biotechnology, digital currencies and so on, there’s growing political appetite for the EU taking a more active role in nurturing technology champions of its own. Germany’s economic minister Peter Altmaeir has mused about the creation of an “Airbus for artificial intelligence”. And at the risk of overusing the Airbus tag, in Brussels Šefčovič has proposed an “Airbus for batteries”.

France and Germany have pushed harder for an interventionist industrial policy in the wake of the Commission’s move last year to block the proposed tie-up between Siemens and Alstom – a decision that left politicians in both countries fuming. The merger had its sights on helping European train makers compete with CRRC, the Chinese railway group. The French and German governments are now among the main advocates for an easing of EU competition rules to allow states to create mega-companies. Several member states are also seeking powers to step in to acquire high-tech companies if they are about to be taken over by state-backed predators. The most prominent example was a German-led demand this spring for EU investment in a local vaccine company, CureVac, that the Trump Administration was said to be seeking to control. Within days – light speed for Brussels – the company was presented an €80 million EU finance package.

Caught between the US and China

Indeed, much of the political momentum for this European shift can be credited to two men: Donald Trump and Xi Jinping. The tech sovereignty push is a way for Europe to hedge against an unreliable US embodied by a president openly hostile to the EU, and the rise of Beijing’s authoritarian system, now more widely seen as a cause for fear.

China is gaining ground in a range of technology fields that experts say could give the country an economic and military edge, including AI, microchips and quantum computing. Von der Leyen’s administration has signalled stronger willingness to confront Chinese protectionism, which some argue poses an existential threat to a vibrant digital economy and the EU’s future prosperity.

China restricts most foreign competitors to its tech businesses. Few foreign companies are allowed to reach Chinese citizens with ideas or services, but the world is far more accommodating to China’s online companies. Admittedly, this is beginning to change. US moves against the popular TikTok app could be the start of wider restrictions on Chinese internet platforms. And a number of countries, including Australia, the US and the UK, have blocked, or are in the process of blocking, China’s Huawei from supplying equipment to their next-generation mobile phone networks.

Magnified by the virus

The broad reassessment of supply chain security in Brussels is magnified, of course, by the ongoing COVID-19 crisis.

The outbreak has revealed innumerable frailties in the world economy, and drawn painful attention to an overdependence on others for key technologies and supplies of crucial materials. As the crisis deepened in the spring, Breton said that Europe may have gone "too far in globalisation" and become too reliant on "one country, one continent."

Governments caught cold by the pandemic are now shifting their attention to bolstering medical supply lines. EU officials say as much as 90 per cent of basic chemicals required for generic medicines are sourced from India and China. After a hapless chase for tests, masks and protective equipment during the early days of the corona-crisis, many politicians feel it’s just too risky to rely on other countries for these things again.

Sovereignty doubts

What does all this amount to?

Some doubt there is a coherent vision, or common understanding, for tech sovereignty, and argue that it’s not clear how much Europeans will gain from the strategy. “The precise meaning of sovereignty or autonomy in the realm of technologies remains ambiguous,” concludes a report from the European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE), a Brussels-based think tank.

“Sometimes it feels like more attention is given to the branding rather than the actual substance of EU foreign policy,” says Niklas Nováky, research officer at the Martens Centre, a think tank affiliated to the centre-right European Peoples’ Party. The continent’s path towards tech sovereignty remains an aspiration and the ad hoc policy toolbox that has been presented so far may well prove inadequate to build the co-ordination needed for a forceful European strategy. Moreover, European governments, facing massive fiscal deficits, are still struggling bitterly over the size of the bloc budget, meaning the best-laid investment plans could still come a cropper.

So nobody knows yet what will come of the EU effort. You can reach into the past and find some successful European state-sponsored attempts to compete with the US, such as Airbus and the Galileo satellite navigation network.

You can also find plenty of half-baked attempts. Indeed, EU Framework Programmes for years have tried and failed to jump-start serious EU competition in computer technologies – from memory chips in the 1980s to social media platforms today. Policy makers advocating for tech sovereignty “tend to ignore failed industrial policy initiatives, including sunk public investments and protracted subsidies for industrial laggards,” according to the ECIPE.

The results aren’t always pretty. One initiative was Quaero — the €400 million search engine aimed at breaking Google’s search stranglehold. It was cooked up by France's President Jacques Chirac and Gerhard Schröder, then German chancellor, in 2005, and eventually put to bed in 2013. Surveying the effort, engineer Nick Tredennick wrote that: “Going head-to-head with Google with a project involving well-funded, energetic entrepreneurs would be foolish. Attempting the same with a multi-government collaboration is beyond description.”

Global industry players privately express concern over the fuzzy, nationalist rhetoric around sovereignty and they fear arbitrary, politically driven decision-making. The tech sovereignty push is ostensibly on behalf of European manufacturing. But it could prove a drag on competitiveness if it increases prices for components and incites foreign retaliation.

The coronavirus crisis “could be used to justify more EU or national government interference in Europe’s digital transformation,” says ECIPE. “Indeed, for some the debate about European technology sovereignty is largely about designing prescriptive policies, which paradoxically risk reducing Europeans’ access to the innovative technologies, products and services that helped Europe through the crisis.”

A Europe newly obsessed with growing its own strategic assets may not sound like an environment that encourages big foreign investment, either. Europe’s strategic autonomy goal could complicate relations with Washington and Beijing at a perilous juncture in global political relations.

A reshoring of selected critical industries, particularly medical supplies, has been mooted in Brussels, though how it would work in practice is yet to be defined. Will we see a wave of factories returning to Europe? Many multinationals may decide that the benefits of outsourcing will still prevail beyond the virus. According to some trade analysts, supply chain resilience is improved by spreading out production around the world, not concentrating it in Europe. A more attainable goal, they say, is diversification away from China.

There are also political obstacles to the sovereignty goal within the bloc, with smaller nations wary of Franco-German firms getting unfair advantages. The virus has cratered the world economy, but the huge sums mobilised in Berlin and Paris to aid recovery are a reminder that the pair are better positioned to come out stronger than many of their neighbours.

Join our Tech Sovereignty workSeptember 8 2020 marks the opening of a major new Science|Business project exploring the concept of technology sovereignty, with a leading-edge conference entitled ‘Industrial R&D: Europe first?’. This will examine further what this stark change of direction away from a blanket 'Open Science, open to the world' European policy means for R&D, tech and industry. But the discussion doesn't stop there. Responding to the sector’s uncertainties about how this new approach may change organisational strategies and priorities, Science|Business will be forming a steering committee to reflect on the conference outputs and plan concrete actions to help European R&D take a step forward in the right direction. If you are interested in being involved please contact Gail Cardew: [email protected] |

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.