An anthropologist studying conspiracy theories is just the second researcher in the country to win a European Research Council grant, a small step forward as Slovakia struggles to improve its research system

Ela Drazkiewicz-Grodzicka, a Polish-born anthropologist, has become just the second researcher based in Slovakia to win funding from the European Research Council, a success that underlines the shortcomings of the country’s science system.

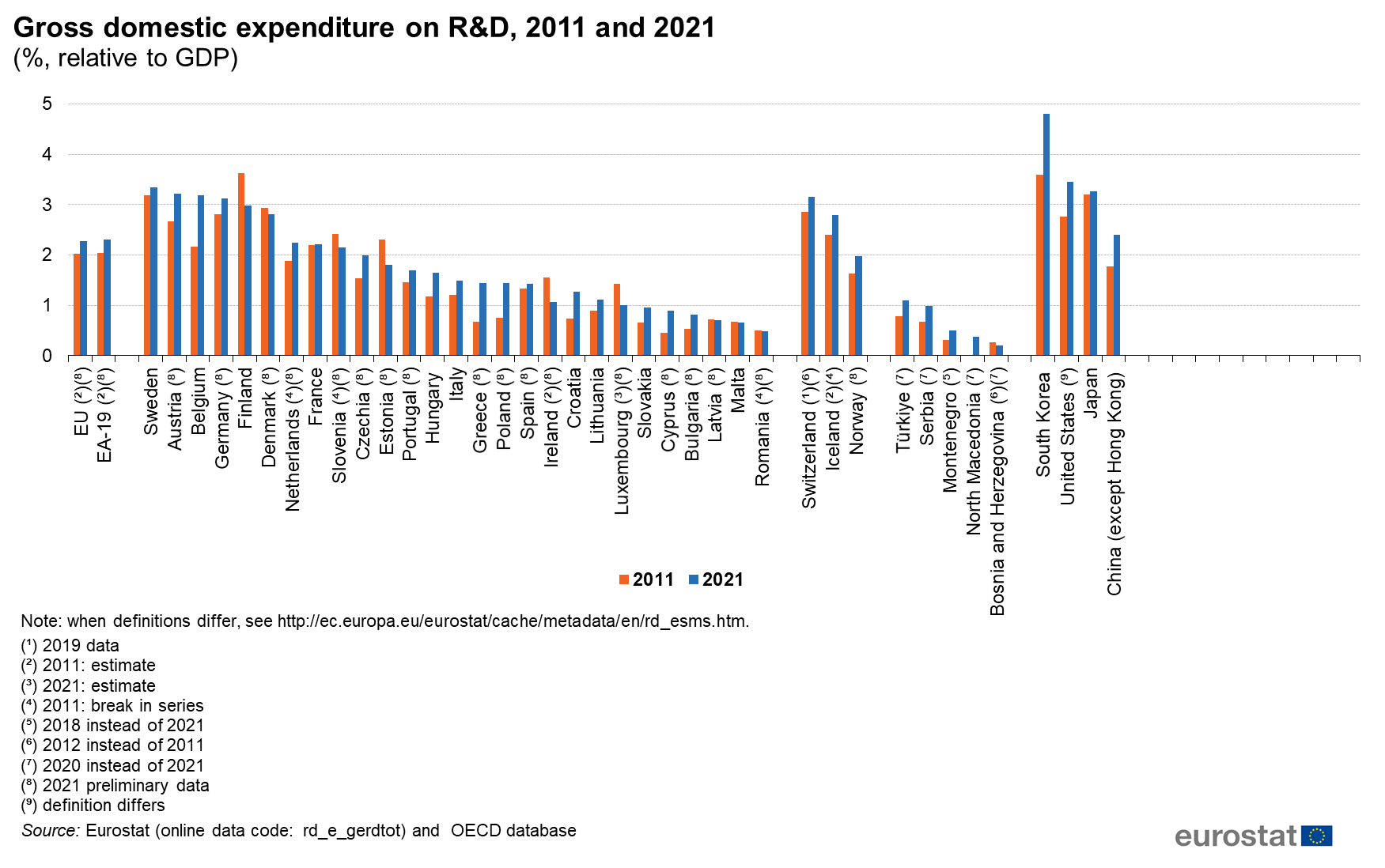

Slovakia puts less than 1% of its GDP into R&D, one of the lowest in the EU. It is ahead of Romania, Malta, Latvia, Bulgaria and Cyprus, but near neighbours, Poland, Hungary and Czechia, all spend more and in general win more European research funding. The average percentage of GDP spent on R&D in the EU is 2.27%.

The only other Slovakia-based researcher to win ERC funding is the chemist Jan Tkač who won two separate grants in 2013 and 2018. Rresearchers based in Germany were awarded more than 80 ERC grants in 2022 alone.

Drazkiewicz-Grodzicka’s award might indicate Slovakia is turning a corner, but she said it was rather her own experience and connections that counted. “I don’t think anyone believed I would get through to the interview,” she told Science|Business. “I felt like on one hand people were like ‘sure, try it’, and on the other hand it was like ‘let’s see what happens here, is she mad?’”

Having moved from Ireland to Slovakia in 2020 to work at the Academy of Sciences, Drazkiewicz-Grodzicka can compare and contrast the situation in the two countries. In terms of finance and opportunities, they are similar. But the big difference is Ireland’s investment in research support to help find external grants, Drazkiewicz-Grodzicka said.

“What is important is for me to break the narrative that everything is great in the west and in the east there is nothing. I think there is something special about Slovakia, but we really need to change things here.”

This sentiment is widely shared. The country’s national grant agency, the Slovak Research and Development Agency (SRDA), says while the lack of funds for research and development is not the only challenge in Slovakia, “it can be considered one of the main problems”.

Jozef Masarik, vice rector for science at Comenius University Bratislava, put it more starkly, saying, “I think that science is not considered important in our country. We are near the end of the scale in terms of investment in the EU.”

Weighed down by paperwork

Apart from low public spending, other factors holding back development of Slovakia’s science base include the number of top university students who chose to study abroad, the lack of funding stability and inconsistent R&D policies.

But perhaps the most cited reason is the huge amount of bureaucracy researchers have to wade through to get funding.

“Many researchers doing high-quality research are not applying for grants as they are afraid of huge administrative duties,” Masarik said. “When I compare the bureaucracy I had to do when applying for a US-supported grant, it was much less than compared to the European grant. And a European grant is much less bureaucratic than a Slovakian grant. When you do not have supporting staff, you are in trouble. Then the scientist has to become the administrator.”

Zuzana Reptova, the Horizon Europe national contact point in Slovakia and the person Drazkiewicz-Grodzicka attributes to helping her the most in winning ERC funding, agreed. “The amount of bureaucratic work that is part of a researcher’s job is unparalleled compared to what I have seen elsewhere,” she said. “It is more focused on preventing people from cheating rather than on the scientific content of a project.”

Reptova said the bureaucratic burden to get money from Horizon Europe is far less than going through national schemes in Slovakia, but that researcher managers and administrators are more used to dealing with EU structural funds, which are more complicated. “So, when it comes to supporting scientists applying for Horizon funding, they push them towards going into the nitty gritty of details, like working out costs for conferences they will attend over the next five years. That stuff does not matter with Horizon, but it is what they are used to.”

SRDA, which supports around 150 scientific projects per year through a general grant call, recognises this. A spokesperson said the agency introduced several changes in 2022 to reduce the administrative burden of grant applications.

It is also trying to bring more objectivity to its review process and in 2023 evaluations will be carried out exclusively by international experts.

“We hope that the adopted and planned changes will positively reflect in the peer review process, which will become more transparent and objective, and that only the best projects will be supported,” the spokesperson said.

Private sector initiative

Aside from money and bureaucracy, there is a need to improve the research system and support for researchers. Masarik said that in the past the government has been reluctant to back improvement schemes.

He previously worked with the SRDA on three schemes, to attract young talent to the country, to support applications for European funding, and to improve cooperation between academia and entrepreneurs. “All three were approved by the government, they were happy we did this, but then they told us we would have to find the money for it ourselves,” said Masarik.

Martin Venhart, first vice president of the Slovak Academy of Sciences, said in the face of a lack of government support, private companies have stepped in.

As one example, ESET, a Slovakian software company specialising in cybersecurity, set up an annual science award in 2019. The company also set up a mentoring scheme to help researchers applying for ERC grants and last year supported two Slovakian scientists who achieved a B grade in the first stage of an ERC application to re-apply. One of the scientists was Venhart, a nuclear physicist.

“It is very rare that a private company directly funds fundamental research. Usually, they fund applied research. This is a different case,” Venhart said. “ESET is doing fantastic work, but it should be the cherry on top of the cake. The problem is we don’t have the cake and we’re trying to put the cherry on nothing.”

Masarik agreed private companies are a vital lifeline for researchers in the country. “ESET is maybe the best example but there are many other international companies active in Slovakia like IBM, for example.”

Pandemic recovery funds

There is much hope being placed on Slovakia turning around its research and innovation performance through the use of the EU’s €672.5 billion Recovery and Resilience fund that was set up to help member states recover from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Slovakia is getting €6.3 billion from the fund. The biggest chunk is going to climate objectives and digitalisation, but there will be support to improve its research performance, which the European Commission highlighted as being “weak” and “fragmented”.

Masarik said it is important that the government follows through on plans set out in the recovery fund to boost R&D performance. “I hope the recovery funds will make a big difference but not all funds we have had in the past have been used very effectively, so I’m afraid in this case they will not be used in a clever way,” he said.

As she prepares to start her research into conspiracy theories, Drazkiewicz-Grodzicka is hoping that her success can inspire others in the country. “I really see how people want to change now. They saw me getting this grant and they think maybe they can do the same. And I believe they can.”

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.