Barriers being put up by the US, China and the EU could hinder scientific progress at a time when it is most urgently needed, according to OECD’s latest report on the global R&D outlook

US President Joe Biden with Chinese leader Xi Jinping – the heads of the world’s two leading countries in terms of science and technology. Photo: 李 季霖 / Flickr

China, the US and the EU’s race to control their own scientific advances and cut out supply chain dependencies could lead to a “decoupling” of research activities at a time when collaboration to solve global issues is crucial, says a stark report by the OECD.

In this year’s science, technology and innovation outlook, published today, OECD paints a picture of schism between the three global poles considered leaders in science and innovation.

The report highlights how the efforts of all three to better control their supply of resources and technological development is causing disruption to the approach of recent decades, which was centred more around openness and collaboration.

“Growing policy efforts to reduce technology dependencies could disrupt integrated global value chains and the deep and extensive international science linkages that have built up over the last 30 years,” the report says.

“These developments could lead to a decoupling of STI activities at a time when global challenges, notably climate change, require global solutions underpinned by […] international co-operation.”

Three-horse race

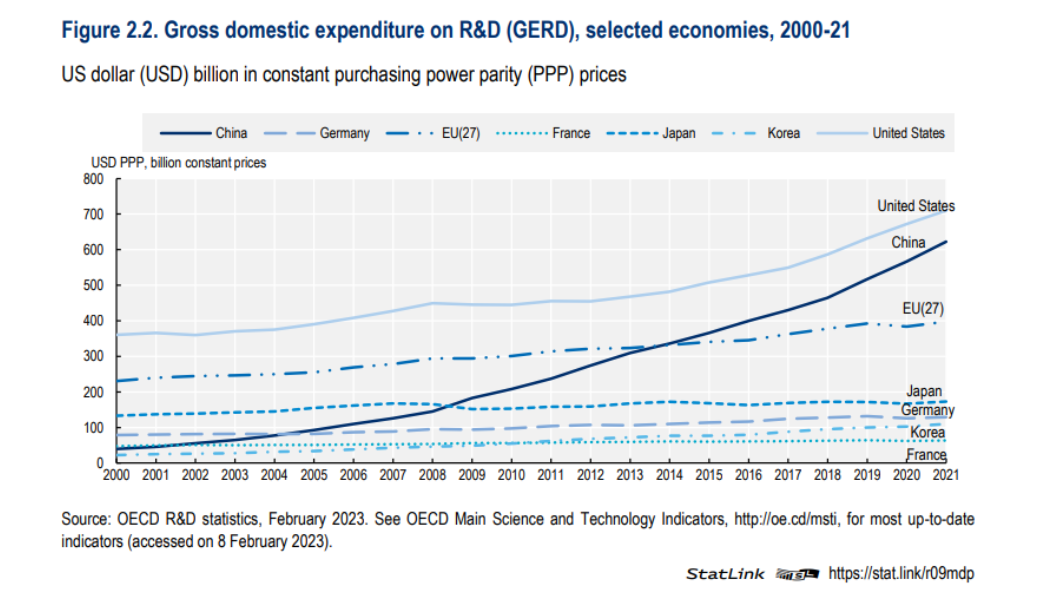

The report highlights the extent to which the US, China and the EU dominate the global science, as illustrated in the graph below.

While there are three distinct poles, the relationship between them is lop-sided. This boils down to a difference in systems and values, which naturally puts the EU and the US on one side and China on the other.

As one notable case in point, last week, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen travelled to the US, where she and US President Joe Biden agreed to coordinate strategies on green technologies and energy.

The move was partly defensive on the European side, with huge incentives for green energy projects about to flow from the $700 billion fund set up under the US Inflation Reduction Act.

That set the EU on edge, with the fear of losing companies and competitiveness to the US, and leading to the recent decision to relax state aid rules to allow national governments in Europe to subsidise similar projects, as part of the EU Green Deal Industrial Plan.

While the meeting sent out a message that that the EU and the US will coordinate their green tech incentives schemes, it also signaled a willingness to work together against the competition, namely China.

The joint statement put out by von der Leyen and Biden does not pull any punches, saying, “We are increasing our cooperation to prevent the leakage of sensitive emerging technologies, as well as other dual-use items, to destinations of concern that operate civil-military fusion strategies

The US openly recognises and refers to China’s strategy to develop its army into a world superpower as ‘Military-Civil Fusion’.

This reinforces the OECD’s view that the technology race is being run by liberal market economies on one side, and China on the other.

But there is more nuance to it than that, said Alice Pannier, head of French think tank Ifri’s Geopolitics of Technology programme, speaking at a meeting of the European Parliament’s future of science and technology committee (STOA) on the topic of strategic autonomy last week.

“We don’t yet have solidified blocks that are quite separate from each other, instead we are in flux. Every government is [examining] how much collaboration they can engage in,” she told Science|Business.

“The truth is so far not much has changed in terms of the supply chain or collaborations, but there is this feeling of things being in flux. The organisation of global alliances and even global governance is being redefined.”

The question of collaboration versus competition also applies to relations between the US and the EU. There have long been discussions about the EU’s high military dependency on its cross-Atlantic partner with many of Europe’s leaders advocating more self-sufficiency in the defence.

“Obviously Europe has its own military dependencies on the US, which are problematic on many levels and there has been a debate going on for decades about how to get out of this dependency, or how much the EU should become militarily autonomous from the US,” Pannier said.

“While that military dependence does exist, that doesn’t mean they are economically in the same basket,” Pannier said. “Obviously the US and the EU have huge trade and investment links, but they’re also economic competitors in a healthy and normal way.”

The oxymoron of ‘open’ strategic autonomy

While the OECD outlook was launched today at an event co-hosted by the European Commission, its tone appears to be more direct than the EU’s usual messages about its relationship with China.

The Commission did not immediately respond to questions from Science|Business about whether the conclusions of the report will feed into the EU’s policies on international scientific collaboration, its handling of China, and what it generally refers to as ‘open strategic autonomy’.

Although the definition of that term remains vague, it is about to be put under the spotlight with Spain highlighting the issue as one of its priorities when it takes over the presidency of the EU in the second half of this year.

Even if the EU’s China strategy is yet to be clearly articulated, the practical consequences of putting up barriers are already being played out.

The German government, for example, last week announced a decision to ban phone operators from using components needed for their 5G networks made by Chinese companies Huawei and ZTE.

The Netherlands meanwhile announced its intentions to introduce new export restrictions on world-leading semiconductor manufacturing equipment made by the Dutch company AMSL.

The move was put forward in a letter to MPs by foreign trade minister Liesje Schreinemacher on 8 March. “Given the technological developments and the geopolitical context, the government has come to the conclusion that the existing export control framework for specific equipment used for the manufacture of semiconductors needs to be expanded, in the interests of national and international security,” Schreinemacher said.

China was not named in the letter, but the measures will impact it by restricting access to an essential technology, with ASML being the only supplier of photolithography machines that are needed to make the most advanced semiconductors.

The restrictions come after reports of pressure from the US government, which imposed export controls on China last year to prevent it from accessing advanced chips.

As another straw in the wind, the Institut Pasteur has withdrawn from activities at its Shanghai-based institute, which is co-managed by the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS).

A spokesperson for Institut Pasteur played down suggestions that this was linked to a wider move away from French collaboration with China, saying the foundation and CAS wish to maintain ties in the future through a different form of collaboration, and the two organisations will continue to work on research projects together.

“France and China share a rich history of cooperation in the field of health, which goes far beyond the partnership between the Institut Pasteur and CAS,” the spokesperson told Science|Business.

While these may be isolated examples, the sum of the parts supports the OECD’s view that global scientific collaboration is starting to run into more and more political trenches.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.