Two new laws are intended to ensure a commitment to increase public and private investment in research will survive changes in government. The aim is for total spending to reach 4% of GDP by 2030

Finnish Prime Minister Sanna Marin. Photo: FinnishGovernment / Flickr

Finland has set in motion a plan to boost research and development by pumping an extra €280 million of public money into the sector each year between 2024 and 2030.

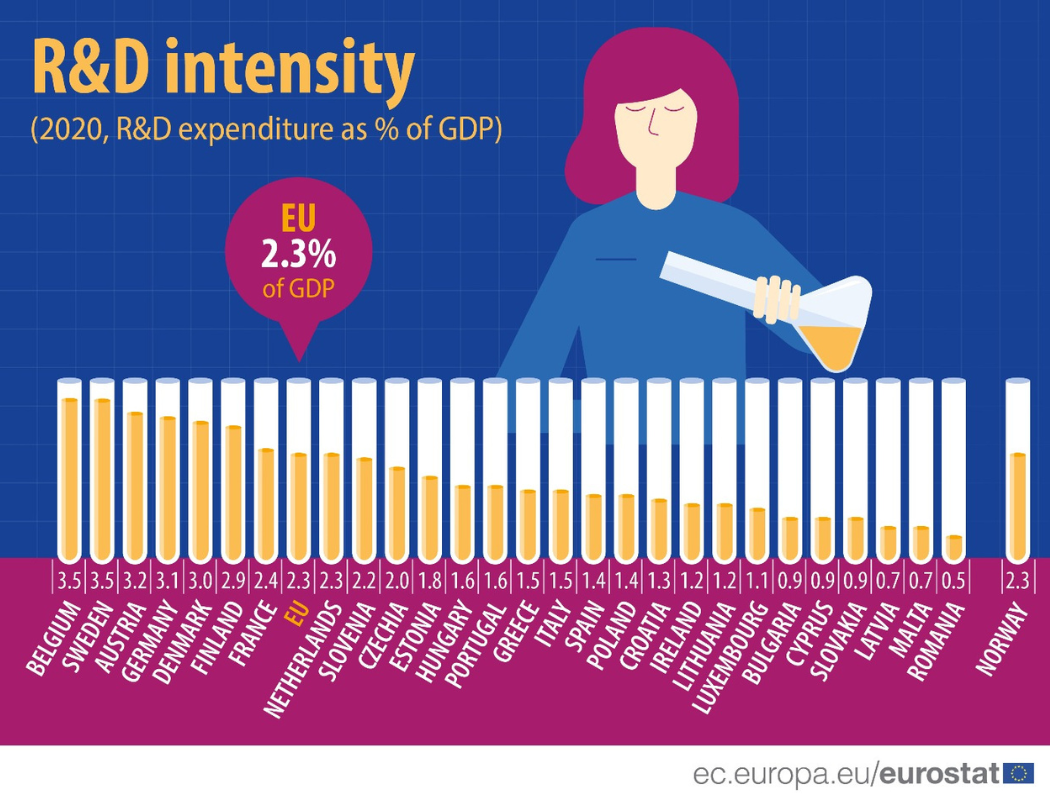

The ultimate goal is to increase public and private investment to 4% of the country’s GDP by the end of the decade. It currently sits around 2.9%, although the final 2022 statistics will not be available until later this year.

If the country does achieve the 4% target, it could make it one of the EU’s biggest spenders on R&D, with most countries struggling to achieve the more modest 3% objective by 2030 agreed by individual member states.

To achieve this, the government has made major changes to R&D policies and budget.

First, the Act on Research and Development Funding, which came into effect at the beginning of the year, will see the state R&D budget grow from €2.4 billion in 2023 to €4.3 billion in 2030.

The act rests on a consensus reached by all the main political parties in 2021, in which it was agreed there needs to be a long-term R&D strategy. Previous attempts to commit to long term budgets have fallen away due to changes in government or political disagreements.

A second new law introduces general and permanent tax incentives to companies investing in R&D. This is mainly aimed at SMEs and is a major change in direction for a country that has previously only offered fixed-term R&D tax credits.

Antti Pelkonen, science adviser in the prime minister’s cabinet, said the changes will be a “huge boost” to the Finnish R&D system. He is quite confident the legislation backing public investment in R&D will outlive any changes in government. In an early test of this, Finland is holding parliamentary elections next month.

“Many politicians have recently stated that it is very important to really stick to this commitment and not to withdraw from it,” Pelkonen told Science|Business. “Of course, a government in the future might overturn the law, it’s possible, but at this moment I’m quite confident that it will stay in force – that’s what it was all about.”

Strong performer

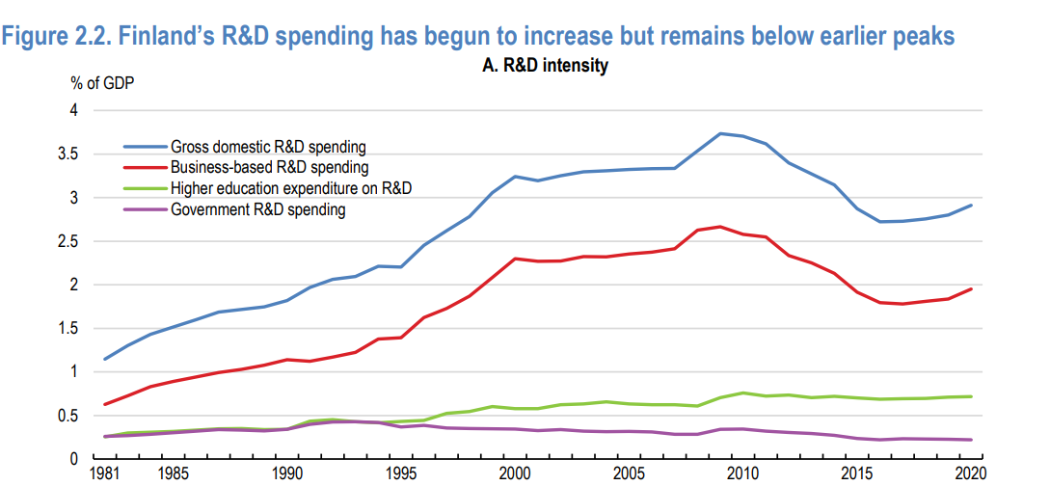

Finland’s target of increasing R&D spending from 2.9% to 4% is not totally uncharted territory. Back in 2009, R&D intensity was 3.7% of GDP. But this quickly fell away throughout the 2010s, and despite a more recent uptick, it is still considerably lower than at its peak.

Many in the sector point to the dramatic demise of Nokia as a major contributing factor to this drop off. The former market leader in mobile phones reached its peak in around 2007 but quickly lost ground to its competitors and almost went bankrupt in 2013.

Since Nokia’s fall from grace, there has been a notable decline in private spending on R&D in the country.

“One major reason behind this fall was Nokia, it was huge compared to the size of the Finnish economy,” said Laura Juvonen, senior vice president of strategy at the VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland.

She said it was not the only issue, with political decisions also having an impact, such as a cut-off in funding to link basic research and academia to industry.

“That was harmful because industry invested into more incremental R&D, rather than longer term goals,” she said.

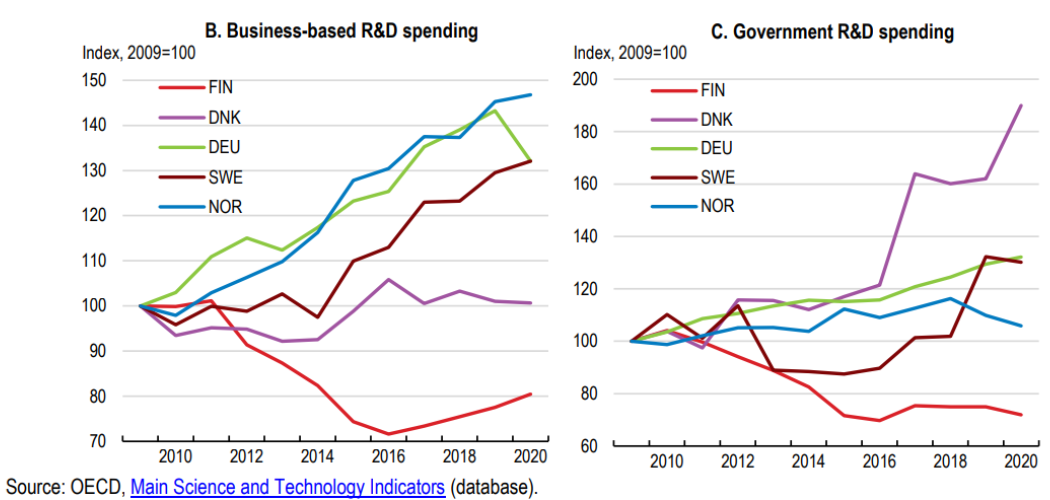

The graph below on the left shows how private R&D spending in Finland fell throughout the early part of the 2010s. And, importantly, this dip was not backed up by an increase in public R&D spending, which, as the graph on the right shows, also dropped following the 2008 financial crisis.

For this reason, the government has coupled the increase in public R&D spending with a drive to get more companies investing in research. It is banking on the private sector making up around two-thirds of the 4% R&D intensity by 2030.

“Business is very dependent on the ability to produce new innovations and with big global changes going on – like the digital transition – they see it is important to invest in research,” Juvonen said.

For Pelkonen, this is the goal behind the tax incentives law. “We definitely need more SMEs to conduct R&D and to increase R&D activities,” he said. “It’s become clear that many of the direct subsidies that we have, small companies are not so eager to apply to them, so the tax reduction might be a better incentive for them.”

How to spend it

All of which begs the question of what the extra money flowing through the system will be spent on.

This was the focus of a report by the parliamentary RDI working group published at the beginning of March, which was delivered to Finnish prime minister Sanna Marin.

One key message is that improvements will not necessarily flow from just pumping more money in, and the report picks out several areas of the Finnish R&D ecosystem that need to be improved for the increased state budget to have maximum impact.

It calls for Research and Innovation Council to be strengthened and to give it a bigger role in shaping R&D policy in the coming years. It will mean restructuring the management of the Council and giving it greater resources.

At the same time a list of national strategic priorities should be drawn up so Finland can target the innovation areas it wants to lead on.

“We cannot invest in everything as we are a small country,” Pelkonen said. Any work on these strategic choices will probably start after the elections in April, he said, and would be led by the Research and Innovation Council.

The report also points to the lack of skilled labour in Finland, which means that there has to be more focus on investing in higher education, particularly at the doctoral level.

“We can’t reach this target of 4% without increasing the number of people working in R&D,”said Minna Hendolin, director of impact at the University of Eastern Finland. It is estimated that to reach the 2030 target, there will need to be 9,000 new R&D specialists. “That is a lot in a short time,” she said.

Part of the answer to the skills shortage will be to attract international students and staff. Hendolin says the fact that the government strategy appears to be focusing on academia is important.

Alongside attracting overseas talent, the report says Finland should concentrate on boosting international collaborations, and also on linking research to industry.

For Juvonen, these two factors are crucial. “We have already made tremendous progress in reforming R&D,” she said. “Now it remains to be seen how actual investments are made. We need to pay attention so that we really do direct a large part of the additional investment to collaboration between research and industry, in areas in which we might have expertise.”

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.