A lack of funding for high quality research is highlighted in a report looking at the importance of science and innovation in addressing future challenges and bolstering the EU’s place in a ‘new global order’

A new European Commission report says the EU’s €95.5 billion funding programme for research and innovation, Horizon Europe, needed an extra €34 billion to fund all high-quality proposals received in 2021 to 2022.

In total, 71% of high-quality proposals did not get funding, just a slight improvement on the previous framework programme, Horizon 2020, under which 74% of high-quality proposals did not get backed.

At the same time, there is a growing laundry list of challenges, from innovation to speeding up the green and digital transitions, to helping the bloc secure strategic autonomy in the global technology race.

Technology leadership spearheaded by Horizon Europe will be key to maintaining the bloc’s geopolitical leverage. “A strategically autonomous EU accounting for 30% of global R&D is a very different prospect than a strategically autonomous EU responsible for 20% of global R&D,” the report says.

There is still time to reorientate Horizon Europe. In the first two-and-a-half years, the EU spent just over €16.3 billion from the seven-year programme, signing over 5,500 signed grants. A further 7,108 proposals have been selected for funding, but according to the latest figures from the end of 2022, the majority of the budget is still to be dished out.

The report lays the groundwork for change in its analysis of the first three years of Horizon Europe and an accompanying assessment of the role research can play in addressing future challenge.

This forms the basis for a plan outlining the direction of Horizon Europe’s final years between 2025 to 2027 that is due to be published in the first quarter of next year. This will be accompanied by initiatives, such as a fresh batch of industrial partnerships. Here, we publish the Commission's new research chief Mark Lemaître’s explanation of the report.

Alain Mermet, director of the Brussels office of the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), speaking on behalf of the G6 group of Europe's six largest research performing organisations, said the analysis made clear the EU will need to invest more in talent and high-quality research. “Brain drain and attractiveness of European research is definitely a critical issue that requires immediate and concrete actions,” he told Science|Business.

More strategic than ever

Researchers have already told the Commission the second half of Horizon Europe should put climate change, energy supply and biodiversity loss centre-stage.

Responding to a survey, 90% of respondents rated climate change as one of the top priorities for the next decade, 88% listed energy supply, and almost as many cited biodiversity loss. They also listed healthcare, global industrial leadership, preparedness for disruptions and social justice as high priority challenges.

But the near future is unlikely to be any less tumultuous, and the Commission wants the bloc to be ready to deal with unexpected crises and changes in the world order.

At the same time, many warn against being too prescriptive when it comes to research topics. Julien Chicot, senior policy officer at the Guild of European Research-Intensive Universities, fears the hyperfocus on strategic issues may leave little space for curiosity-driven research, which has proven to be key in solving global challenges, such as the recent COVID-19 pandemic.

“We expected such orientation of Horizon Europe towards more impact and strategic use for geopolitical reasons, but we are a bit uncomfortable with that, because we have the feeling that Horizon Europe is more and more used as an implementation instrument, not an R&I policy instrument,” says Chicot.

While it makes sense to use research to tackle global challenges, Chicot notes the report could have used more analysis on how to best divert research money to policy and whether strictly mandating what research is most needed is effective. “We want directionality, but is the way we do directionality the most effective?” asked Chicot.

Mermet echoed the concerns. “Basic bottom-up research is an indispensable ingredient for advancing technologies and disruptive innovation; it requires stronger support across all the instruments of Horizon Europe,” he said.

Poles apart

The report acknowledges the shifting sands of global geopolitics, saying the new world order is likely to be “multipolar”. It suggests three different possible outcomes: the world could move towards closer collaboration to tackle global issues; it could separate into “antagonistic groups” that still collaborate on a limited number of issues; or there could be at least one power openly hostile towards the others. The inference is that the poles will likely form somewhere between the US, China, Russia and the EU.

The focus on future outcomes “makes sense”, according to Joep Roet, deputy director at the Netherlands house for Education and Research, who said that global developments such as COVID-19 and the Ukraine war have “repeatedly taken the EU by surprise”.

“The question is can the EU rise up to [these challenges] and use R&I to secure its position in the world?” he said. Horizon Europe still has many issues, for example the Missions element casts a narrow focus on certain topic areas such as soils, oceans or cancer, while an overlap and competing interests between different instruments under Horizon Europe, has caused confusion.

For Roet, a challenge that is not answered in the report, is how to combine top-down directions with bottom-up research without adding too many layers and instruments that attempt to achieve the same objective and overburden the policy making machine, “As I would argue has happened with Horizon Europe.''

Scientific standing

The EU is still a “scientific powerhouse”, producing 20% of the world’s scientific output despite only representing around 6% of the global population.

However, while 80% of all new patent applications filed under the Patent Cooperation Treaty come from China, the EU, Japan and the US, the EU’s share has been decreasing in the past two decades.

In 2000 the EU was the source of 31% of global patent applications. That fell to 19% in 2018. The US saw its proportion fall from 38% to 22%, highlighting the dominance of China in technological advances this century.

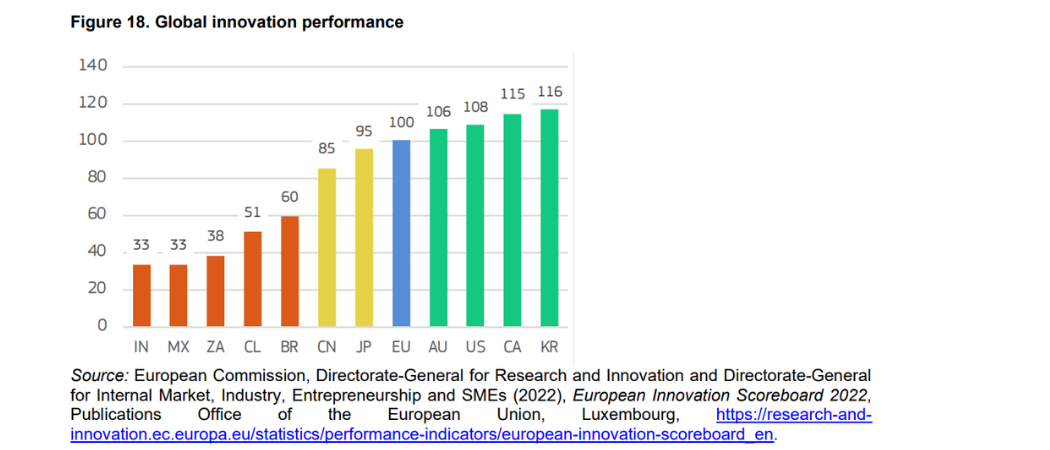

In terms of innovation, the EU is the fifth best global performer, according to the European innovation scoreboard, having overtaken Japan between 2015 and 2022.

As for R&D intensity, which is the amount spent on R&D in proportion to gross domestic product (GDP), the EU has improved, going from 1.81% of GDP to 2.32 in the past two decades.

But it still finds itself far below South Korea, which dedicates 4.81% of its GDP to R&D, the US 3.45%, Japan 3.27% and China, just under 2.5%.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.