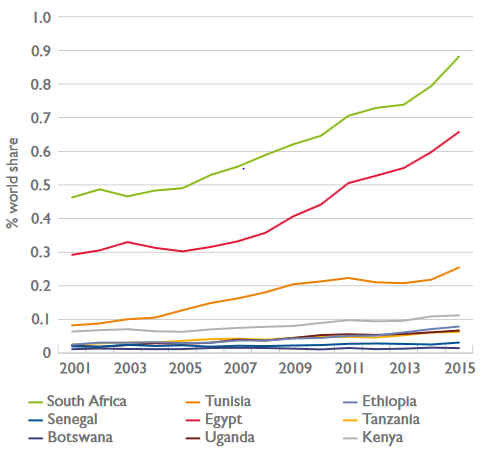

The country leads Africa in science and technology, but economic and social problems persist

South Africa is the strongest research player in Africa, with deep roots in astronomy, agriculture, health and social research. But the country’s persistent budget and social problems have hit the research sector as well – even as the government looks to science and technology to help solve those very problems.

The country has a history of performance in science and innovation: the first heart transplant in the world, the invention of the CAT scan, and soon the world’s largest radio telescope. Since the end of apartheid in 1994, the country has managed to develop its research infrastructure to one that look outwards at the same time as it tries to solve its main domestic challenges.

Source: Stellenbosch University

And those challenges are great. In December 2019, the unemployment rate was 29 per cent, and 49 per cent of the adult population live below the poverty line. So far, COVID-19 has not been as devastating in South Africa as elsewhere; as of 4 May, there had been 131 deaths reported. But the global economic fall-out is expected to hit hard at South Africa and other parts of the developing world this year.

The government has long viewed science and technology as one way to help solve some of the country’s problems – through education, innovation and technological development. For instance, in 2018 the government announced plans to boost economic and inclusive growth, identifying key opportunities in Big Data, green economy and small companies. And it has had some success: since apartheid, South Africa has managed to triple the number of scientific publications, raise the participation of women and blacks in research, and raise the number of doctoral graduates. But calls for further progress on inclusion are intensifying, and last year it ranked 63d in one oft-cited academic measure of innovation performance, the Global Innovation Index.

Money is tight

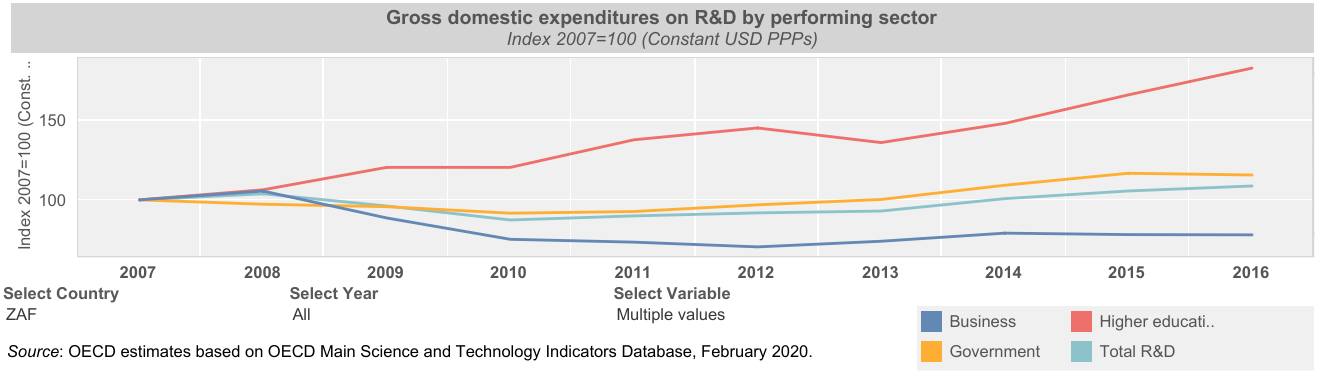

As a percentage of gross domestic product, R&D spending is stuck at about 0.8 percent – short of the government’s 2020 goal of 1 per cent. That’s much higher than the African average of 0.3 per cent, but below other countries more comparable to South Africa such as Malaysia, Portugal or Turkey.

The country’s scientific strengths stem party from the apartheid era, when the government invested heavily in military R&D. Today, South Africa is a particularly strong player in astronomy, as co-host of the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) project to build the world’s largest radio telescope. The country is also strong in research in malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS.

But its business R&D has struggled of late. Business spending dropped to 39 per cent of the country’s entire R&D expenditure in 2015, down from 51 per cent in 2001, according to a government-commissioned report last year by Stellenbosch University. Reasons included troubles at some of the country’s biggest companies, and others moving their R&D abroad.

Academia and demographic change

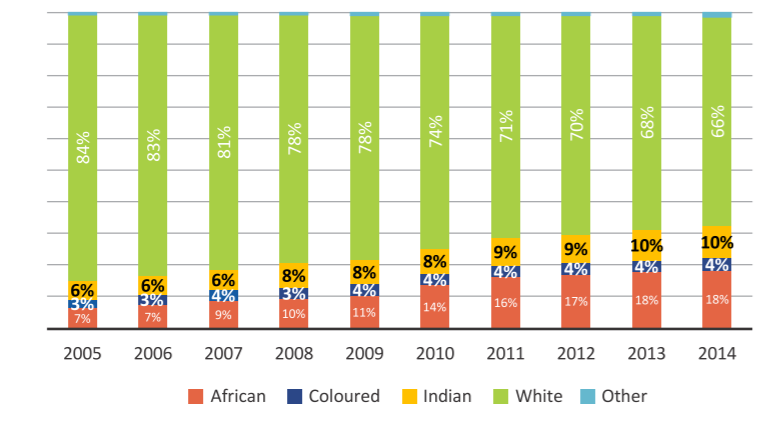

The university sector is of course vital to the government’s plans – and also politically sensitive. According to Nature, 49 per cent of South African university researchers and educators are white, whereas only 8 per cent of the general population is white. However, a recent study found the share of black researchers rising steadily since 2005, and forecast more black than white scholars within the next decade. A major reason: a growing population of young blacks entering the research world, as older white researchers approach retirement. But a counter-trend is also at play: Many of these young researchers don’t stay long at university, moving to jobs in the private sector or government agencies.

When it comes to gender in research, the picture is brighter. The country has a high proportion of female researchers, accounting for 44 per cent of all researchers, which is higher than the average of many OECD countries. The share of publication by women scientists has increased as well from 20 per cent in 1998 to 32 per cent in 2014. In the academic sector though, they only accounted for 14 per cent in 2015. The government plans additional measures for gender balance, such as targeting support to women researchers and technology entrepreneurs.

The highest ranked university, according to one standard measure, is the University of Capetown (UCT). It was founded in 1829 and is the oldest university in the country. It has one of the most diverse student communities in South Africa. Five alumni and former staff members with UCT have won the Nobel Prize. Another alumnus, the late Dr. Christiaan Barnard, performed the world’s first heart transplant.

The country’s second-ranked institution, the University of the Witwatersrand, is a leading institution for paleo sciences. University of KwaZulu-Natal and University of Johannesburg have made it back on the list after being absent for one and two years. Newcomers to the list are the North-West University and University of South Africa.

For the South African research world, international collaboration has become essential. By 2015, 52% of its research papers were with foreign co-authors.

Bilateral R&I relations between South Africa and the EU are coordinated through a Science and Technology Cooperation Agreement, first signed in 1996. In Horizon 2020, the EU’s just-ending seven-year research programme, South African researchers have received a total of €40.8 million so far. In all, 161 grant agreements have been signed – and the country’s applicants are running a 21 per cent success rate, nearly twice the Horizon 2020 average. In addition, more than 61 South African researchers have participated in Marie Skłodowska Curie Actions, permitting them to work in other countries.

One milestone in SA-EU relations have been in health research and innovation. The European and Development Countries Clinical Trials Partnership is recognized as one of the reasons. Another important research area for both the EU and South Africa is ocean science. It was identified as a priority in 2014, in the light of achieving sustainable development goals and addressing climate change. The goal is to increase operational efficiencies by maximising the use of large research infrastructures, and access to and management of data.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.