Not all aspects of international science cooperation are to the liking of researchers and policy makers in central and eastern Europe. They want to see the innovation gap fixed before the EU spends more money abroad

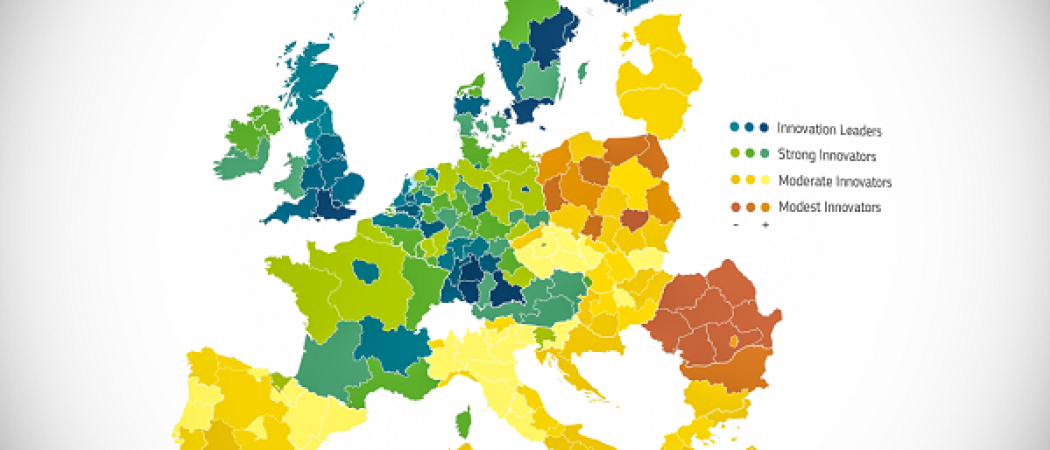

Data from the regional innovation scoreboard by the European Commission shows a significant R&D performance gap between EU member states

Before the EU further opens its research and innovation funding programme to countries all over the world, researchers and policy makers in central and eastern Europe call for help strengthening national systems in poorer member states which are lagging behind.

“To paraphrase [US President] Donald Trump, let's make the European science great again in Europe first and then open to third countries,” Mateusz Gaczyński, deputy director for innovation and development at the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland told Science|Business.

Poland has recently passed a reform of its research and innovation system that helped create a network of applied research institutes and a dedicated agency to attract home expat researchers, in a bid to stop brain drain and boost performance in Horizon Europe.

Gaczyński acknowledges that without opening to third countries EU will not be able to make its science and innovation system more competitive globally, but wants the EU to focus on European problems before looking further. “First things should come first,” he said.

This view has been echoed, with different emphases, by researchers and academics elsewhere in central and eastern Europe. For the most part, they agree the EU should be thinking about ambitious investment in research across the world as part of future planning, but say the innovation gap between rich and poor member states should be fixed before venturing further outside its borders.

For Marcin Pałys, rector of the University of Warsaw, it is important for Europe to be involved in international scientific cooperation. “We must not isolate ourselves from the rest of the world,” he told Science|Business.

But there are caveats. Reciprocal cooperation that entails, for example, Australia or Japan opening their labs to EU researchers is okay. Likewise, the association model proposed by the European Commission, in which third countries can contribute to the EU research budget in order to get access to funding calls, is also acceptable for central and eastern European countries.

But Pałys is worried about “financing that [results in a] net flow of money from EU funds to third countries.”

Another point of concern for Pałys is that international cooperation could affect the cohesion inside European research, if EU-funded projects help countries like Canada or the US suck up more talented researchers from central and eastern Europe, a region which is already affected by the migration of talent to richer countries in Europe.

Poorly organised national systems

The EU has the largest civilian research programme in the world, but the distribution of funds among member states is biased towards richer countries with strong national science systems. Researchers in countries where national systems are poorly organised and funded feel the EU programmes should also work towards reducing that bias, in addition to promoting scientific excellence.

“I do not feel it is ethical to move money outside the EU, until the within EU discrepancies are halted,” Andras Báldi, a researcher at the Centre for Ecological Research of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences told Science|Business.

Báldi argues the EU should work outside its borders to achieve its geopolitical ambitions in climate change and artificial intelligence, but it should avoid funding projects that are entirely outside of the EU. “That is not very good,” he said.

Others say cooperation complimenting European research and innovation should be encouraged, especially in projects where European members take the lead. International cooperation in Horizon Europe “could be seen as a development programme for European good practices, in areas of the world where US leadership is retracting,” said Markus Dettenhofer, director of the Central European Institute of Technology (CEITEC) in Brno, Czech Republic.

Dettenhofer believes the EU should “assume the role of world leader“ in research and innovation.

It won’t be easy for policy makers in Brussels to find the right balance between these complaints and the ambition to have a larger footprint abroad. But, according to Pałys, the EU could first set up a pilot programme for third countries, with a limited budget. That way, the EU can figure out how these collaborations work in practice, “without facing the risks of diverting big money to third countries,” said Pałys.

Another idea would be to introduce an offset mechanism, which would require third countries receiving money from the EU research programme to invest in the EU. According to Pałys, this system has already been used successfully in defence cooperation. For example, if a country like Romania buys military equipment from the US, then US companies are expected to invest in Romania.

Europe first?

During Horizon Europe negotiations last year, Romanian MEP and Horizon Europe co-rapporteur Dan Nica said the motto of the programme should be “Europe first”.

He has since toned down this approach, but now that budget cuts seem to be imminent, Nica said the EU will probably dial down its “remarkable” ambition to fund research projects throughout the world. These ambitions, Nica said, “Will have to be reduced and prioritise projects coming from member states.”

Nica made the comments earlier this month, as rumours of difficult budget negotiations among member states began circulating in Brussels. Some countries want a slimmer budget overall, while others lament the European Commission’s plan to shift money from cohesion policy and agriculture towards science and technology.

But not everyone agrees with this approach. According to Igor Papič, rector of the University of Ljubljana, the argument that Horizon Europe should diminish its international outlook and focus on the innovation gap does not hold and efforts should be made to preserve the proposed research and innovation budget as a whole.

“The much bigger concern for me is the new attempt that we should drastically reduce the budget for Horizon Europe,” said Papič. “[International cooperation] is not an obstacle to fixing our problems.”

Research and innovation programmes could be badly hit by the budget tussle. German MEP Christian Ehler and Horizon Europe co-rapporteur was the first to announce a potential €12 billion cut from the European Commission’s proposed €94 billion for the next EU research and innovation programme.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.