An overview of China’s rapid S&T progress shows how it was driven by government money and planning – despite mounting complaints of unfair practices

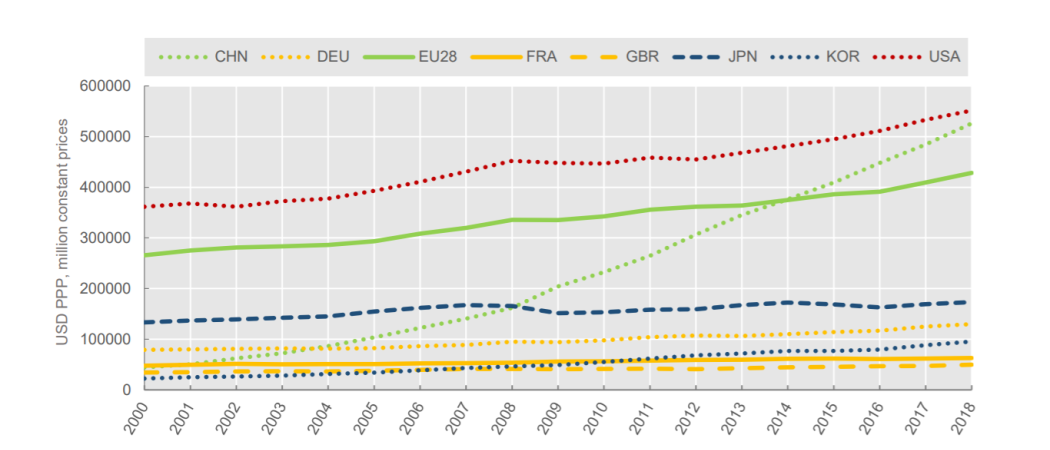

Gross domestic expenditure on R&D, 2000-2018

In the past decade, China has emerged as a powerhouse of science and technology, a result of deliberate central planning and heavy spending. But with that growth have come mounting complaints about the Chinese approach to sharing data, protecting intellectual property and, in some cases, conducting research ethically.

The rapid rise of Chinese science and technology is historic – more impressive even than such well-known tech success stories as South Korea and Singapore. As China moved from the world’s factory to one of its tech powers, the Chinese government pumped money, sent its students around the world, developed a series of master plans, boosted patenting, and took a progressive stance towards changing the whole science, technology and innovation system.

China has turned into an international challenger in fast growing high-tech areas such as artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, nanotechnology, biotechnology, quantum computing and Big Data. The UK Research and Innovation Agency projects that China will overtake the US in 2022 as the No.1 nation for R&D investment.

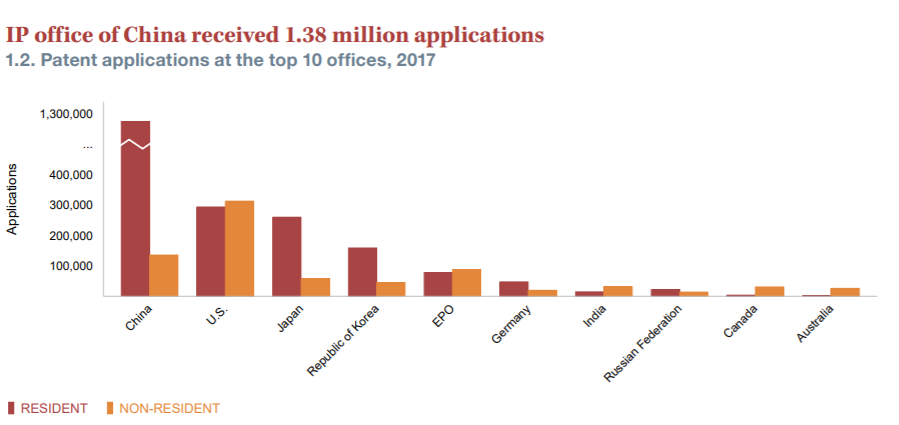

Already by 2017, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development estimated that China accounted for 23 per cent of total world R&D expenditure. And the following year, its spending continued rising to account for 2.19 per cent of gross domestic product, from 2.15 per cent in 2017 – slightly greater than that of the European Union. China has 25 per cent the world’s R&D workforce, and ranked second among countries filing the most international patent applications in 2018 (53,981), just behind the US (55,981).

Complaints also on the rise

But with this growth have come increasingly strident complaints from other trading partners.

(Chinese officials, when asked for comment, supplied only online links to some previously published government information.)

IP protection has been the main source of friction. Foreign companies operating in China have complained for years about copyright violations, and being forced to transfer technology to China in exchange for market access, investment access or regulatory approvals.

US President Donald Trump, in his Twitter storms, has been most vocal. “They have stolen our Intellectual Property at a rate of Hundreds of Billions of Dollars a year, & they want to continue. I won’t let that happen!” he Tweeted last August.

Likewise, last November Trump’s technology advisor Michael Kratsios said “China stole our intellectual property […] If we don’t act now, Chinese influence and control of technology will not only undermine the freedoms of their own citizens, but all citizens of the world.” And this fight played out just last month at the World Intellectual Property Office, as the US lobbied successfully against a Chinese candidate becoming head of that organisation.

But IP is not the only source of complaint. Within the EU, several researchers who have collaborated with Chinese scientists have complained about not getting full access to data they wanted for their research – and in the early days of the COVID-19 crisis, researchers from Australia to the US complained that the Chinese, while publishing a gene sequence of the virus, had not promptly made virus samples available. Prior to COVID-19, the most notorious case of a Chinese lapse in research ethics was in 2018, when a researcher in Shenzhen announced the birth of twin girls whose genomes he had edited in an effort to prevent them getting HIV from their infected father. The Chinese government, stung by the resultant international outrage, jailed the researcher.

How has China managed to get there?

Still, China’s rise in science and technology is a case study of government willpower. While building for years, the long-term master plan for change came in 2006 when the government set a target of being the world leader by 2050.

Since then, the state’s five-year plans have pushed growth in several sectors, including smart city technologies and industrial alliances. For instance, the Chinese housing and development ministry chose 193 local governments and economic development zones as smart city pilot project sites. These sites were then qualified to receive funding from the China Development Bank, with an investment fund of 100 billion yuan ($16 billion).The current five-year plan includes a greater focus on the environment, boosting innovation capabilities and GDP, and improving he life of its citizens.

Cheerleading for the growth has been Chinese leader Xi Jinping. For instance, from 2013, the year he was named Communist Party general secretary, he began pushing the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) to become a world-class research institution. And among his most ambitious initiatives has been the “Made in China 2025” industrial plan. The aim, since its 2015 launch, is for China to become world leader in a number of high-tech industries, such as medical devices, robotics, and aerospace equipment. The goal is to achieve 70 per cent self-sufficiency within these industries.

The plan is not good news to all. Stressing terms like “indigenous innovation” and “self-sufficiency”, the government is putting in place incentives for Chinese enterprises that, foreign critics say, disadvantage non-Chinese companies. Just this year, European industry lobby BusinessEurope called on the EU to put more pressure on China to allow “reciprocal access” to Chinese-funded projects. In the US, Trump has been urging companies to “start looking for an alternative to China, including bringing your companies HOME and making your products in the USA.” Others worry that China’s strategy of controlling entire supply chains is risky for the wider world. In the COVID-19 crisis, for instance, Apple’s iPhone production plans were disrupted by supply problems in China.

Exporting students, boosting publications

Another factor in China’s S&T growth has been its decision to train thousands of its brightest students in top Western universities. Indeed, China is a net exporter of students: 662,100 students went abroad in 2018, while 492,185 international students from 196 countries came to China, according to the Chinese Ministry of Education. In the US for example, Chinese students make up the majority of international students, accounting for more than 369,000. But increasingly, the Trump Administration has been pushing US universities to be more careful about what the visiting students - and especially researchers – can get access to.

But it is a two-way street. Several Western universities have set up R&D research centers and universities in China. One example is the opening of Cambridge University-Nanjing Science and Technology Innovation Center in 2018, which was the first cooperative research institution ever to be established outside of the UK by Cambridge. One of its current projects is “to create a high resolution scanner that can provide a low-cost easily accessible method for examining difficult areas of the body, such as bent spines, without using large and expensive CT scans.” Other universities that have established R&D facilities in China are Stanford University, Imperial College London, Oxford University and the National University of Singapore.

According to an index published by WIPO, Cornell University and INSEAD, in 2019 China ranked third behind the US and UK when it comes to quality of universities. Its highest ranked institution is Tsinghua University, followed by Peking University and Zhejiang University.

On scientific publications, in 2017 China surpassed the US in 2017 in sheer number of scientific publications. In fact, Chinese publications have risen by an astonishing 15 per cent annually for the last two decades. Its strength has been in chemistry, physics and material science, with medical publications growing fast over the past decade. But the surge was partly because Chinese researchers had often been paid for publications. Recently, the government told institutions to stop the practice, as it incentivises quantity over quality. And in fact, the US still leads when it comes to having the most top-cited publications, according to the OECD.

The EU and China

The EU has been trying to get to grips with China’s R&D rise for years – with mixed results. From 1998, the EU and China have had formal science and technology cooperation agreements; and in 2018 the two sides published a “roadmap” for cooperation. They also announced a package of flagship-initiatives as a way of boosting cooperation. These have been translated into co-funding mechanisms through Horizon 2020 in fields including surface transport, agriculture, biotechnologies, aviation, health, environment, sustainable urbanisation and food. At the same time, the two sides have agreements to cooperate on fusion and fission energy.

But Commission officials complain that China hasn’t delivered on all its promises for co-funding EU-China research under Horizon. The original plan, for 2016-20, called for the EU to spend a total of about €500 million and China 1 billion yuan (€130 million.) And as of February this year, there were 464 instances of Chinese researchers participating in Horizon projects. But so far, the Chinese have actually committed only about 60 per cent of their promised funding.

Last year, after a meeting with Chinese counterparts, then-EU Research Commissioner Carlos Moedas called for reciprocity: “The EU and China both recognise that research and innovation are vital to ensure our future prosperity and to tackle global challenges. Together, we can do this better. That is why we want to step up our cooperation in research and innovation in areas of mutual interest, based on fair framework conditions in the spirit of reciprocity”.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.