Research and innovation in central Europe is held back by the emigration of scientists and engineers. Rather than framing policies around encouraging their permanent return, the EU should help universities establish brain networks, in which modern communications enable scientists in the diaspora to contribute to research at home.

As a recent Science|Business article highlighted, central European universities are stuck in a Catch 22. To improve their standing they need to attract funding from EU framework programmes that award grants on the basis of excellence. But starting from behind, and with demand far exceeding supply, they find it difficult to compete with their counterparts in the west of Europe.

This difficulty drives - and is compounded by - the brain drain, which sees the best and brightest central European scientists and engineers take up posts in the world’s leading universities in the EU and the US.

There are endless debates about how to attract them to return. But as long as conditions in the countries of origin do not improve, this brain circulation is unlikely to be more than a trickle, and will not compensate for the size of the original brain drain, as is highlighted in the OECD 2017 report on global migrations and brain drain.

Of course, researchers have always been one of the most mobile groups of professionals, and in many senses, this issue is as old as science itself. But the era of the internet and instant global communications could provide a solution, through remote approaches to running and managing research projects, in other words, brain networking.

In a 2008 survey published in the journal Science and Public Policy (Ciumasu, 2010), I found that Romanian scientists in the diaspora would be in favour brain networking, and that their main concerns about working at universities in Romania are not about salary, but working conditions and professional perspectives.

There is a body of evidence showing diaspora networks can be a game changer in the national science, technology and innovation standing of any country, rich or poor (Lewing & Zhong 2013). They can also lead to transnational entrepreneurship, as an effect of knowledge spillover (Veréb & Ferreira 2018), and could help developing countries escape the middle income trap (Chalapati, 2015).

The Department of Brain Networking

The numerous implications and potential benefits of brain networking extend way beyond a viewpoint article. My purpose here is to simply signal that we should avoid getting stuck in the old false dilemmas, rhetorical traps and sterile disputes between rich and poor countries about gain and loss of human capital (for further discussions, see Ivancheva & Gourova, 2011; Apostolov, 2012; Niu, 2013; Murakami, 2014; Chávez, 2016; Opute, 2018).

Some narrowly-focused politicians and administrators insist on restrictions on free movement of people, and advocate limits to scientific freedom and excellence (like quotas, or partisan moral positions). That demonstrates a lack of understanding of what science is and how it works, which is likely to leave accomplished scientists abroad unwilling to be involved in their country of origin - and mean the brain drain continues.

If, however, central European universities move to defend quality standards and take the initiative in brain networking, by establishing dedicated teams and units with responsibility for stimulating and facilitating brain networking within each institution, science and innovation in central Europe would have a chance to leap forward.

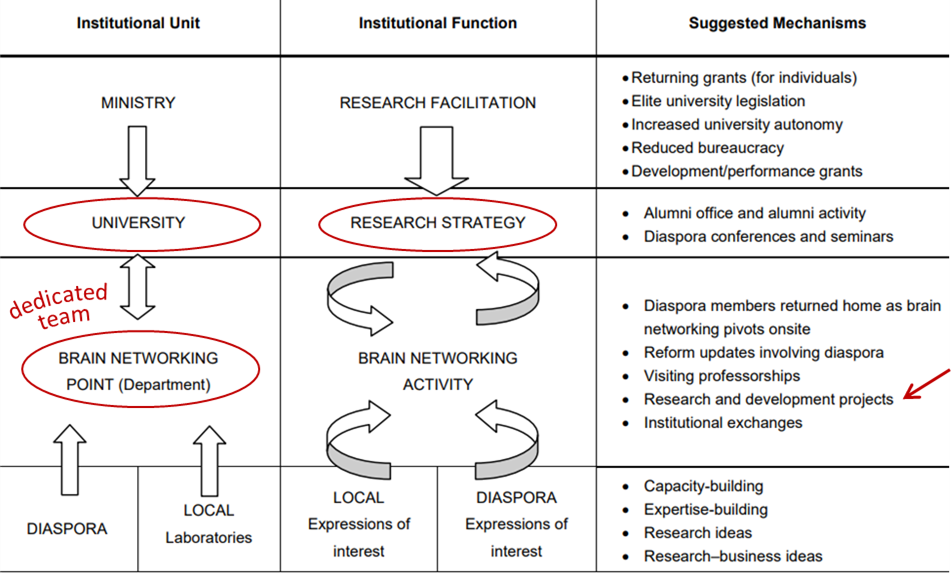

Such initiatives should be led by individual universities, not by ministries of research and education, (which should only provide resources), and must be organised in a way that suits both the universities and the networked scientists, as illustrated in the figure below.

Brain networking implementation scheme. Adapted from Ciumasu (2010)

A university’s Brain Networking unit should be autonomous and have the rank of a department, somewhat similar to the interdisciplinary departments that many universities have established to boost interdepartmental crossovers. It is probably a good idea for interdisciplinary departments, where they exist, to work closely with the Brain Networking unit and help it connect with the nuts and bolts of university life.

While openness is one of the fundamental requirements of science, spontaneous collaboration between scientists is sporadic and usually limited to non-essential topics defined by university and faculty priorities. So, one-to-one collaboration is not sufficient to trigger a leap in the quality and performance of central European universities. Brain networking needs to be lifted from a peer-to-peer level, to an institutional level, where diaspora scientists receive official status as faculty members, so they can represent the university without the need for intermediation (usually unsuccessful, or marginal) by peers.

As a start, they can be given a status reflecting their remote location, as associate or/and visiting researchers and/or teachers. They can be involved in delivering lectures through video, so their physical presence is not needed daily or monthly. Video-conferencing and other internet-based technologies can be used to enable diaspora scientists to participate as team members, just as academics would communicate with colleagues doing field work.

A few visits each year to the university should be enough to ensure they are fully-fledged members of the community of researchers and lecturers, and that they can speak for their institutions, on the same terms as any local scientist.

The net result will be a huge boost in their human capital and the competitiveness of applications submitted to EU projects by central European universities. This would be a good start in building a virtuous circle leading to excellence in central European science and education, with positive spill-overs into industry and business.

Barriers to brain networks

Decades of isolation and underfunding between the end of the second world war and the disintegration of the USSR made the universities of central Europe uncompetitive internationally. The few large-scale programmes set up to change this situation, for example, the Excellence in Research programme, CEEX, that ran in Romania from 2005-2008, had some measure of success, but have subsequently been undone by government policies that can also now be seen as standing in the way of building brain networks.

For example, Romanian authorities do not automatically recognise doctorates issued at the best universities in the world, a totally artificial barrier against involvement of Romanian scientists abroad in the country’s science and education.

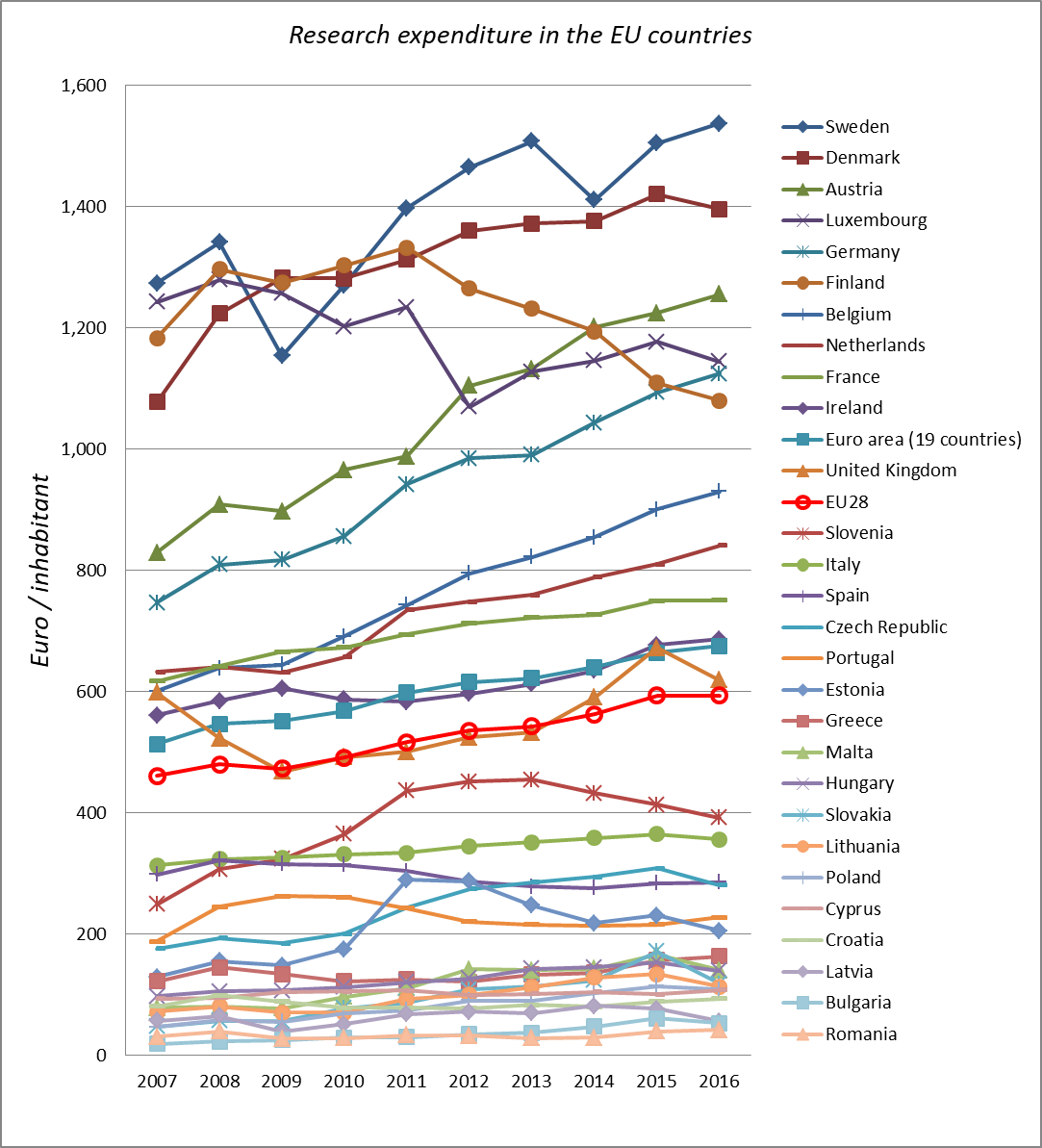

In addition, the current Romanian government has excluded foreigners from being involved in peer review of nationally-funded projects, a move that represents a huge step backward. To this can be added consistently low national expenditure on research, a common feature in central Europe. There are even cases where funding for projects that have already been granted money has been suspended, reflecting disastrously poor management of national research.

For details, refer to the website Ad Astra, an association of Romanian scientists, which systematically documents the situation in the country.

Evolution of the annual investment in research by EU countries in Euros per capita. Source of data: Eurostat

Scientists don’t need protectionism

Given these disparities in research spending, the recent proposition by Romanian MEP Dan Nica, of taking a “Europe First” approach and using national quotas to allocate EU-funded research money in Horizon Europe, may appear a reasonable suggestion. The aim would be to create additional incentives for central European scientists, by making it easier for them to win grants.

However, this approach cannot work, as it is contrary to how science functions. Scientists don’t need protectionism, they need real support from the inside and then to be left alone to do their job jointly with their peers in Europe and around the world. If they can be integrated into the world’s leading edge science via brain networks, central European countries stand a much better chance of increasing their competitiveness and participating in the scientific and economic success of developed countries, via the innovation, investment and entrepreneurship spillovers that take place at the interface between science and business.

In the face of current political and financial pressures exerted by “protectionist” politicians in central Europe, universities must deploy their autonomy to develop better human resource strategies. They also need support and involvement from western European universities – and for dedicated funding to be available to set up and develop Brain Networking Departments in Horizon Europe.

With its ethos of openness and objectivity, science has always had a critical role in society. This is now truer than ever in central Europe, and universities have a key role to play. Let us hope they will rise to the challenge.

Ioan M. Ciumasu is a Senior Guest Lecturer teaching Transitions to Sustainability: Human and Technological Systems, at the University of Versailles Saint-Quentin / University of Paris-Saclay, France, and an entrepreneur working on a project applying knowledge maps to solve scientific and societal issues, bridging natural and social sciences and connecting science, business and society.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.