Horizon Europe one of the few current EU budget lines to get increase in seven-year proposal

EU research commissioner Carlos Moedas is responsible for Horizon Europe. Photo: European Commission

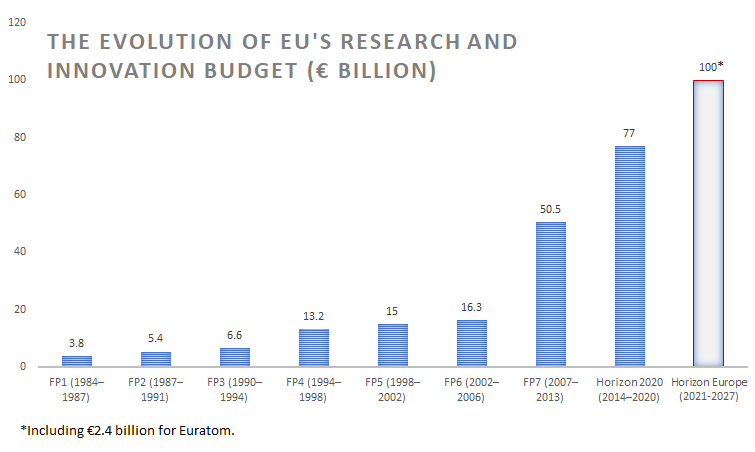

The European Commission on Wednesday outlined a €100 billion budget for its new research programme, running between 2021 and 2027.

The figure includes €97.6 billion for Horizon Europe, the EU’s flagship research programme, and €2.4 billion for the Euratom nuclear research programme. For Horizon Europe, that’s an increase of almost 30 per cent – when adjusted for inflation – on the EU’s existing research programme of €77 billion. Without the inflation adjustment, it’s a less-inspiring rise to €86.6 billion – though Commission officials are promoting the bigger number.

The Commission sent member states and the European Parliament an overall budget request of more than €1 trillion, equivalent to 1.11 per cent of the EU27's gross national income. The first post-Brexit budget, called the Multiannual Financial Framework, included reductions to the two largest EU spending programmes, farm and regional aid, down 5 and 7 per cent respectively, to make room for more spending on research and defence. Tougher conditions are also placed on member states in receipt of funds, including economic reform and adherence to EU “values” such as rule of law.

“Everyone said we want more for research – it’s happening,” the Commission’s President Jean-Claude Juncker told reporters at the unveiling of the blueprint. The new research programme is one of the few EU budget lines to go up in the Commission’s seven-year proposal; another is the Erasmus+ student exchange programme, which sees its budget double to €30 billion. The Commission also requested €4.1 billion funding for defence research – an increase on the €3.5 billion originally proposed and way up from a current, €90 million pilot programme. The amount, if granted, would place the EU among the top four defence research and technology investors in Europe.

Juncker said it had been “much harder” to find agreement among commissioners on the budget proposal than in previous years, “because we had to take into account withdrawal of the UK”. The President also downplayed suggestions that new rules on cohesion funding would be used to target the likes of Hungary – a country the Commission has tussled with over the independence of its judiciary, and the government’s dangling threat to shutter the Central European University.

Reaction was mixed. Some applauded EU Research Commissioner Carlos Moedas as among the biggest winners, although he himself said, at a conference in Brussels on Wednesday, that “the budget is probably not what we wanted, but it is good news for science and innovation.”

His cause was greatly helped by vocal support from Germany’s EU representative and budget commissioner, Günther Oettinger – a commanding force in Brussels who has repeatedly called for more research investment. But others, such as prominent German MEP Christian Ehler, called the result good but not good enough: he vowed the Parliament will fight for more.

EU research officials say they are very satisfied with the Horizon Europe increase, even if it is less than the €120 billion asked for by the European Parliament, and the €160 billion hoped for by lobbyists. They also were happy to see research and innovation programmes “mainstreamed” through many diverse policy areas, rather than ghettoised into one programme. “Research and innovation have made it to the top of the political agenda,” said Robert-Jan Smits, special adviser on open access and innovation at the European Commission, and former director-general for research. “Mission completed!”

Achieving any kind of budget increase is an impressive feat, officials pointed out, given the loss of the UK’s contribution to the common EU pot. UK researchers were the top beneficiaries of Horizon 2020, winning around €10 billion to date. “The cake is bigger, and the guy that was eating most of the cake is no longer at the table,” one EU official said. Another way of thinking about today’s increase is that, if you exclude the UK’s drawdown, Horizon 2020 has seen €67 billion shared among 27 member states – so some said the increase to €97.6 billion announced on Wednesday was in effect even bigger.

It could have been less. The official proposal on the table last week was about €85 billion – and that number had whizzed around last week in Brussels. “Initially things looked bleaker. [Commissioner] Oettinger made a huge effort” to go beyond €85 billion, another EU official said.

A five-hour meeting ending about 21.30PM Monday resulted in a deal, which was finalised Tuesday morning. An important part of the deal was offsetting cuts to Common Agricultural Policy with more money for food, agriculture, rural development and bioeconomy research – €10 billion now versus €6 billion under Horizon 2020.

“All of the various agri-tech projects we couldn’t support in the past have a chance to get funding now,” the commissioner for agriculture, Phil Hogan, told reporters in the afternoon. “We’d like to run a precision farming programme, but we’re only at the start of the process here.”

The overall research pot could eventually grow bigger, officials say, if rich countries like Switzerland, Israel, and Norway join the programme as expected. The UK has also expressed a wish to access the next EU research programme, in exchange for a membership fee.

Like all EU decisions, the proposal will require many rounds of scrutiny before final adoption. It will need unanimous agreement from the EU’s member countries and consent from the Parliament – a process expected to last more than a year.

How to cover the shortfall left by the UK’s exit has added extra tension to the process of agreeing on the bloc’s long-term spending plan. The UK is one of the biggest contributors to the EU budget and its departure leaves a hole of up to €15 billion a year in the bloc’s finances after 2020.

The fight is only beginning. Already controversial is a suggestion by the Commission to create several new sources of EU-level cash, including a shift of revenues from selling carbon pollution permits under the bloc’s emissions trading system to Brussels, and a new tax on non-recyclable plastics.

Budget hawks such as the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden and Austria have said they don't want to plug this gap, but Germany and France have shown willingness to pay in more. Last time around, during negotiations for the 2014-2020 budget, the Commission saw its original proposal rolled back – €1 trillion was eventually cut to €960 billion after pressure from the UK and some other countries.

Several ministers came out swiftly condemning the proposal. “[It’s] not an acceptable outcome,” Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte said in a statement. “A smaller EU as a result of Brexit should also mean a smaller budget. That entails making clearer choices and spending less.

“The costs of funding the budget are not shared fairly,” he added. “Brexit is already set to hit the Netherlands’ economy hard. This proposal imposes a disproportionately high bill on top of that.” Denmark’s Prime Minister, on Twitter, questioned the size of the budget, too, while France’s agricultural minister called CAP proposals “unthinkable”.

Juncker said he wasn’t surprised by negative reactions. “It’s normal that PMs, without knowing the intricate details, react strongly. When you have to pin numbers on priorities, you have no friends,” he said.

A closer look at the €100 billion figure

If you look closely in the Commission’s legal text, you’ll find two different figures given for Horizon Europe: €97.6 billion and €86.6 billion.

The €97.6 figure (which rises to €100 billion if you add Euratom – something EU officials are doing) refers to "commitments" in Brussels-speak, meaning the maximum that the EU can spend. The actual payments are nearly always lower. The figure also assumes inflation of 2 per cent per year – if inflation turns out to be higher than 2 per cent, this could leave less money for research.

The €86.6 billon figure, which also refers to commitments, is smaller because it does not include inflation. So, depending on how you prefer to do the math, you could say Horizon Europe gets a 27 per cent inflation-adjusted increase, or a less inspiring 2018-euro rise of 12 per cent. Needless to say, research fans inside the Commission Wednesday were promoting the bigger number.

Article updated at 18:05. Come back to www.sciencebusiness.net for updates.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.