New and expanded research and innovation programmes are scattered throughout the EU’s new budget. Here’s a rundown.

For years, leaders of the European Commission’s varied research programmes have been pushing to “mainstream” research and innovation throughout the EU budget. It looks like they’re getting there.

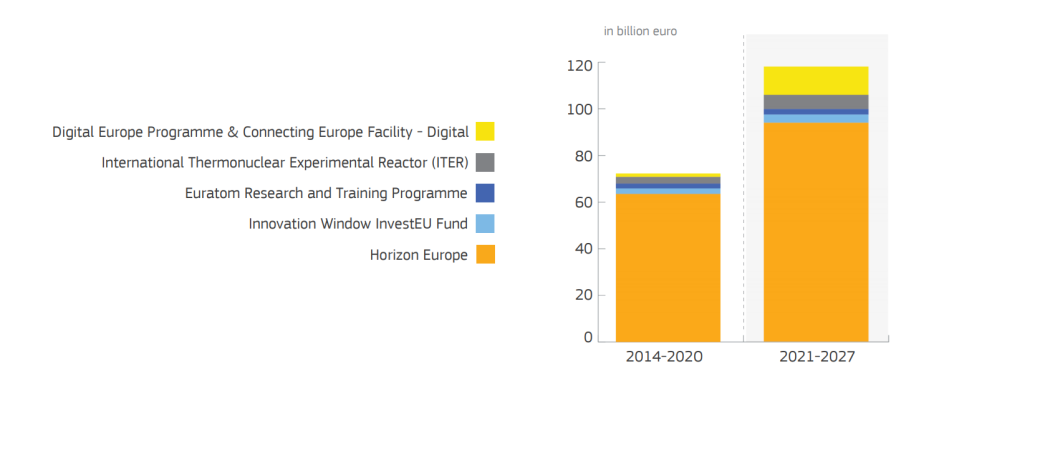

EU budget plans released today show research activities cropping up in many areas of EU policy – not just in the formally designated Horizon Europe research programme. How you add them all up is pretty complex, as there’s lots of overlapping efforts; but one Commission fact sheet puts the R&I total at €114.8 billion from 2021-2027 – or just about 10 per cent of the overall EU budget. But even that number leaves out many other research activities scattered around the Commission.

Here are the major categories:

Horizon Europe, €97.6 billion. This is the flagship research and innovation programme, succeeding the current, €77 billion Horizon 2020. Since the start of these so-called Framework Programmes in 1981, their budgets have soared from an initial annual spend of just under €1 billion to nearly €14 billion under the new plan. Its key parts include individual grants for scientists and entrepreneurs, group grants for collaborative research projects, and a wide range of politically de rigeur research programmes in Europe and across the world. While officially not yet approved, the detailed (leaked) plan for Horizon Europe includes creating a one-stop-shop for entrepreneurs seeking funding; cutting the number and kind of complex, cross-sectoral partnerships; advancing open science; expanding international research collaborations; strengthening east European science and creating high-profile “missions” to appeal to Europeans everywhere. The full plan is to be released June 7.

Euratom, €2.4 billion. This is the oldest EU research effort, dating back to the founding treaties in 1957. It started as a way to develop nuclear energy; but as national rivalry in this field intensified, Euratom switched to the less politicised topic of nuclear safety research. Now, with Germany and some other EU members forswearing nuclear power, it is once again a political orphan – but by treaty it continues. Much of the work is done today by the Commission’s in-house labs, the Joint Research Centre.

ITER, €6.1 billion. “Fusion is the energy of the future – and always will be.” Such is the oft-quoted quip about one of the world’s biggest research projects, the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor. Under construction in Cadarache, France, the project aims to move the world closer to a 60-year old goal of harnessing the energy that powers the stars. The EU and France fund the lion’s share of the budget – and somewhat confusingly, some of the EU money comes out of the Euratom budget (see above.) ITER aims to switch on in 2025, and generate power by 2035.

InvestEU, €15.2 billion. This is another EU attempt at financial alchemy. The idea, pioneered in the so-called Juncker Plan in 2014, is to use a bit of EU money to attract lots of other public and private investment – in essence, reducing the risk of investment for the private sector. Only part of the €15.2 billion allocated is specifically for research and innovation; under the Juncker Plan, 22 per cent went to R&I projects while the rest went into digital, energy, transport and other fields. The aim: to take the EU seed money and use it to attract other investors for a total economic stimulus of €650 billion.

Military R&D, €4.1 billion. War – or the fear of it – is big these days. In the EU budget, defence gets €13 billion overall - and a tiny, €90 million pilot programme on military R&D explodes into a €4.1 billion campaign, run by the European Defence Agency. The rationale: on some basic defence technologies such as drones and special materials, Europe’s defence ministries can save money and time by working together rather than separately. This argument got a push from Brexit: the Brits had long resisted EU defence collaboration as a distraction from what they saw as the main game, at NATO. Many French and German defence contractors, by contrast, have been enthusiastic. This military R&D budget comes on top of the grants that will be provided by Horizon Europe for dual-use security research – such as on cyber and airport security.

Digital Affairs, €9.2 billion-plus. Nearly 40 years ago, Europe’s “technology gap” with the US in computing and electronics was a motivator for the first Framework Programme; now, with Google, Facebook and other American IT companies on a tear, it’s back on the agenda. The budget includes €9.2 billion for a Digital Europe programme to invest in supercomputing, cybersecurity, artificial intelligence, training and other fields. But there’s also €3 billion set aside in the Connecting Europe finance programme to support digital infrastructure, and lots more in Structural Funds. A supercomputer may be needed to figure out how to manage all these efforts coherently.

Synergies-plus, Amount unknown. For several years, the Commission has been striving to overcome its internal turf battles and get its different departments working better together. Research is no exception, with dozens of pockets of research-related activities going on inside agriculture, regional development, transport, energy, health, environment, climate, international relations and other policy fields. The aim: to promote “synergies” among the different programmes. The deal between research and agriculture announced Wednesday appears to be the biggest step forward in years, with an agreement that €10 billion for food and agriculture research will be “ring-fenced” inside Horizon Europe (but it wasn’t clear Wednesday which department will manage what’s inside that ring.) But similar synergy efforts are under way between the research and regional development departments. More news on that front is expected during May, as the Commission finalises plans for the individual programmes.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.