East-West debate over research funding intensifies, as papers urge a new look at EU geography and pay rules

The Visegrad Group urges a new regulation “that guarantees a minimum salary for researchers participating in EU projects."

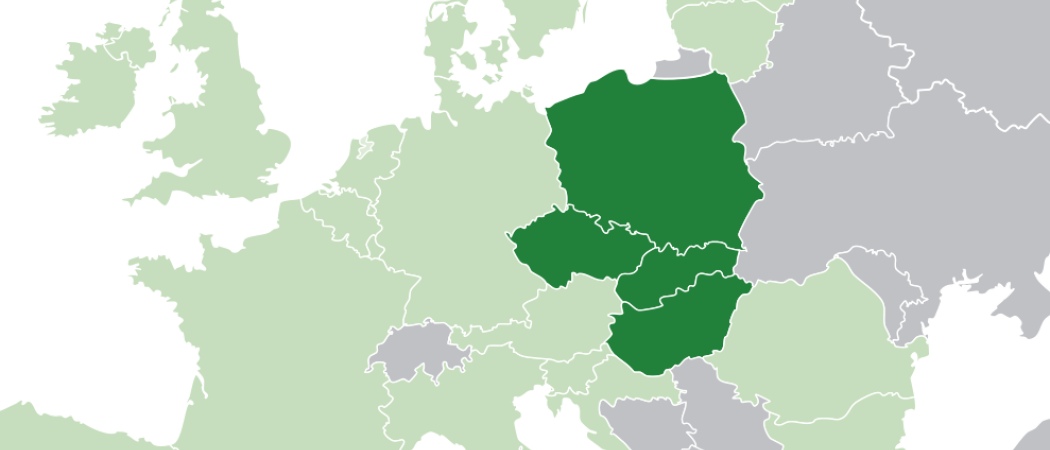

A long-running East-West debate over European Union research funding took a step forward with the release of some proposed rule changes by Poland and its neighbours, increasing their odds of winning a grant and raising their researchers’ pay.

One proposal, by the Polish Science Contact Agency in Brussels (PolSCA), would introduce geographical distribution as an extra, “auxiliary” selection criterion for cooperative research projects. If two competing projects get the same score from European Commission grant evaluators, then the funding would go to the project that introduces a partner from one of the EU 13 countries.

"It’s a matter of positive discrimination,” the acting director of PolSCA, Malgorzata Molęda-Zdziech, told Science|Business.

The second proposal, from the academies of science of Poland, Hungary, Slovakia and the Czech Republic, urges a new regulation “that guarantees a minimum salary for researchers participating in EU projects.” While the Horizon 2020 pay rules are complicated, they are part of a broader complaint, the academies say:

“While lower participation levels and success rates can be primarily attributed to lower levels of national R&D spending, various elements of the design of the current EU framework programme, including evaluation procedures, thematic focuses, eligibility of costs, and excessive administrative limitations, certainly contribute to a growing European divide in science and technology.”

Dividing the Framework pie

The proposals cut to the heart of a growing debate within the EU over how the money in Framework gets distributed, and under what terms. Under the current seven-year, €77 billion programme, called Horizon 2020, most of the grant money is distributed according to three criteria: the excellence of the research or innovation, the potential impact of the work on the economy or society, and how well implemented the proposed project is likely to be, in the view of Commission evaluators.

But this, and other structural problems, has discouraged researchers in EU 13 countries to compete and the number of proposals submitted from these countries is still low. More than 60 per cent of Horizon 2020 applications come from the UK, Italy, Germany, Spain and France.

In the view of many East European member states, the current situation is unfair because they lack the wealthy, well-staffed and well-resourced universities and labs of the richer Western member states. The eastern countries have been increasingly vocal on the issue. So far, the richer Western countries have been resisting major changes. And latest Commission proposals would see a relatively modest reorganisation of funding for what it calls “spreading excellence” around the EU.

Gender gap

According to PolSCA’s Molęda-Zdziech, the idea for a geographical criterion was inspired by gender balance rules under Horizon 2020. The current Framework Programme encourages applicants to secure “a balanced participation as close as possible to 50/50, of both men and women in the teams and among the leading roles.”

This rule could be translated into a geographical balance rule that would help plug the EU’s research gap.

In the same report, PolSCA made some other recommendations aimed at achieving a fairer geographical balance. The Polish agency hopes that the European Commission will maintain and further strengthen the ‘widening participation’ instruments, that it will set remuneration rules that are not discouraging to beneficiaries from the EU 13 and that it will foster synergies between the Framework Programme and Cohesion policies.

The Visegrad paper, meanwhile, addresses another long-standing East European complaint. Under current Horizon 2020 rules, salary increases for successful researchers are not eligible expenses. This is one of the main reasons why researchers from EU 13 countries are discouraged to apply for EU finding. This also hinders the capability of research institutions to attract researchers from abroad.

Another potential solution to solving the EU’s research divide would be the simplification of rules that enable synergies between framework programmes, structural funds and national programmes.

The academies also argue for a more coordinated use of research infrastructure. “[We] encourage actions to improve transnational access to research infrastructures.”

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.