China is turning away from a private-led system, with venture capital investment now lower than in Europe

Photo credits: Solen Feyissa / Unsplash

DeepSeek’s world-beating efficient AI chatbot, dancing robots on China’s most-watched TV show and 1 trillion yuan (€127 billion) in state support for the private sector have rekindled optimism among and about the country’s tech start-ups.

Such good news is a balm for an industry that has been battered over the past half-decade by Beijing’s regulatory crackdown, weak economic growth at home and the tech and trade war waged by the US. But it cannot mask the challenges facing China's state-led innovation model, not least the retreat of foreign direct investment.

Venture capital (VC) in China has been declining since 2021 and dropped another 32% year-on-year to $33 billion in 2024, according to the investment website Crunchbase. This means that China's inbound venture capital was just one-fifth the size of the $178 billion invested in US companies, and even lagged behind the $51 billion flowing into a sluggish European market. What a difference five difficult years can make: in 2020 China’s VC market was one and a half times larger than Europe’s, but by 2024 it was only two thirds the size.

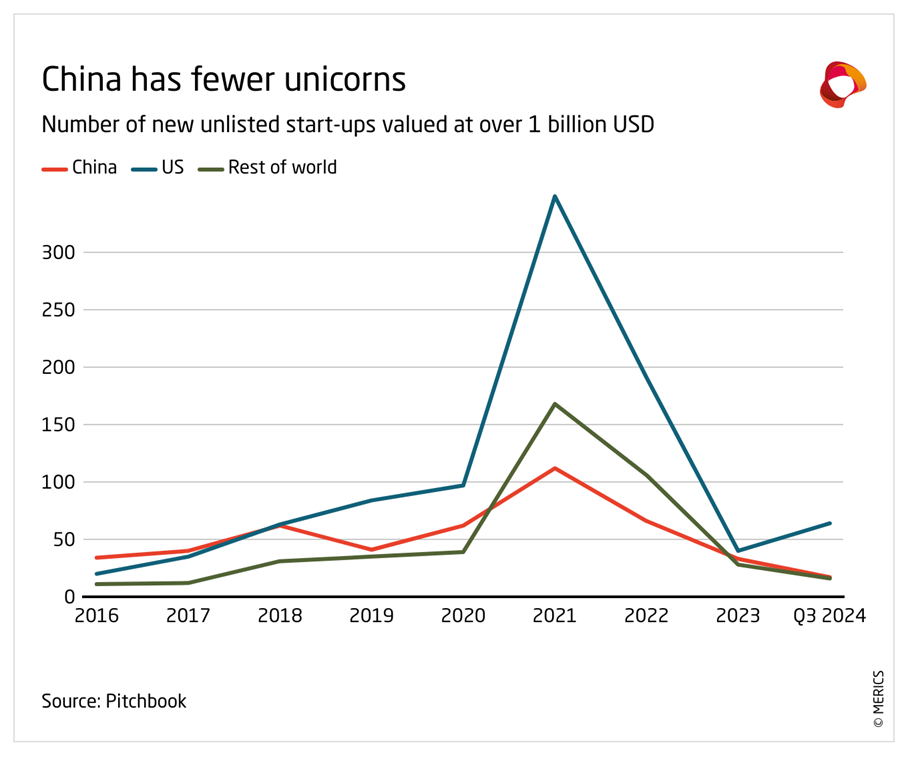

Disappearing unicorns

The first generation of turn-of-the-millennium tech companies, such as Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent, were followed a decade or so later by a raft of second-generation companies, such as ride-hailing firm Didi, fast-fashion platform Shein and TikTok-owner ByteDance. But the frequency and intensity of the emergence of new tech giants has noticeably declined in the 2020s. By 2024, China was producing about two new unicorns (companies worth $1 billion or more) a month, twice the rate of Europe, but only 40% the rate seen in the US.

Declining foreign direct investment in China is a key driver of this trend. The first generation of Chinese unicorns attracted foreign venture capitalists, and invaluable advice on how to scale up, as they sought to list on US exchanges, offering their early-stage investors a lucrative exit. But since around 2020, Beijing has insisted that strategic tech companies must be Chinese owned, effectively scuttling Didi’s US listing in 2021. Meanwhile, in 2025 Washington banned US VCs from investing in Chinese AI, semiconductors and quantum computing.

President Xi Jinping is aware of the challenge facing the technology sector. In 2024 he asked “why do we have fewer new unicorns?” and every major political event since then has heard a call to “invest early, small, long-term and in hard sciences.” Beijing wants its banks, sovereign wealth funds and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to fill the gap left by private investors.

In 2024, SOEs controlled by the central government put 40% of investments into emerging technologies, five percentage points more than in 2023. And this year, Beijing pledged 1 trillion yuan to a government fund for emerging and future industries.

Beijing argues that seed investment from SOEs and the new fund will help attract many times as much funding from the private sector. But it will also further increase the role of the state in the economy. This is, of course, entirely in character. The online response to Xi’s question about why there are fewer unicorns was simply “because of you, Chairman.” Since becoming head of the Chinese Communist Party in 2012, and head of state in 2013, Xi has consistently promoted the advantages of SOEs and party-state control over the economy.

State-led investment

As long as the state, rather than private entities subject to the free play of market forces, decides which companies develop which products and technologies, follow which development paths and choose which partners, China’s economic contradictions will only grow. Despite years of government campaigns, private companies will continue to struggle to access loans and capital, while so-called government guidance funds will continue to allocate resources based on political considerations, with many projects failing to advance innovation, let alone its productivity. The number of tech unicorns will continue to decline.

In Europe, the appetite for industrial policy is also on the rise. Europe’s inclusive, multi-stakeholder approach reduces the risks of top-down decision-making, while built-in sunset clauses ensure that state support remains temporary and limited to a handful of highly strategic sectors.

Related articles

- Xi Jinping’s new ’productive forces’: what researchers need to know

- Chinese export rules make collaboration riskier, researchers warned

- Viewpoint: why China’s switch to an ’innovation chain’ matters to research partners in Europe

In China, state support is the norm and growing, creating challenges of a different degree. For now, these have been eclipsed by DeepSeek and the other “six little dragons of Hangzhou”: the AI-focused startups Game Science, Unitree, DeepRobotics, BrainCo and ManyCore. But the question is: for how long?

All of these companies have benefitted from China’s innovation policies, but they did not emerge through state procurement or government guidance funds. DeepSeek, for example, has primarily been funded by the hedge fund set up by its chief executive, Liang Wenfeng, not by Beijing.

For China to produce the next Alibaba, it should dial down its techno-nationalism, with its state-led approach to technology development. It needs to find its way back to the more inclusive and international investment climate of previous decades, in which entrepreneurs and private investors could thrive. But, despite Xi’s longing for more unicorns, there is no reason to expect that China will change course. The more likely outcome is more dancing robots at the next Spring Festival TV extravaganza. This will please the crowds, but will do little to revive China’s start-up scene.

Jeroen Groenewegen-Lau is head of the science, technology and innovation programme at the Mercator Institute for China Studies in Berlin.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.