Report commissioned by the European Physical Society says industries that rely on expertise in physics contribute 12 per cent of EU economic output

Industries that rely on physics expertise contribute more to the EU economy than financial services or retail, according to a new study.

A report commissioned by the European Physical Society (EPS) says that in the EU, physics made a net contribution to the economy of at least €1.45 trillion per year – or 12 per cent –which is more than retail (4.5 per cent), construction (5.3 per cent) or financial services (5.3 per cent). Physics-based industries, it says, include electrical, civil and mechanical engineering, as well as computing and other industries reliant on physics research.

The EPS paper comes as EU countries debate how much to spend on Horizon Europe, the EU’s next research programme, which will pump billions into scientific research and technological development. The European Commission wants to spend €94.1 billion on Horizon Europe and the European Parliament wants €120 billion, but some member states, particularly Germany, say the Commission’s proposal for the entire EU budget is too big – meaning Horizon Europe could end up much smaller than scientists had hoped.

Given the likely budget crunch, various constituencies in the EU R&D world have been making the case for the value of their sectors. In its Horizon Europe proposal, the Commission hasn’t projected spending by scientific sector – but it has proposed 52 per cent of the budget go to high-profile policy challenges such as climate change, quantum computing and manufacturing competitiveness, which would draw at least to some extent on physics research.

Policymakers should know more about scientific impact

For physics, the “impact has to be made more generally known, especially to policymakers who very often want evidence of short-term benefits,” said EPS President Petra Rudolf at the report’s launch event in Brussels on 15 October.

However, the most important gains from scientific research often come in the long term, she said. “Einstein, when he worked on stimulated emission, certainly did not think of lasers being used to operate on the eyes,” said Rudolf.

She added, “In 1968 the first LCD display was made in a lab,” and the technology is now widely used in televisions. “But the people who developed this technology in the first place, they never did envision the full extent of the technology they were developing.”

Physics-based industries are those that rely heavily on expertise in physics. These include oil and gas extraction, nuclear fuel processing, and various forms of manufacturing like fibre optics, lighting equipment, office machinery, cars, ships and armaments.

Growing contribution of physics to the EU economy

According to the report, the Gross Value Added (GVA) of physics-based industries exceeded €1.45 trillion in every year between 2011-2016. That’s 12 per cent of the total GVA in the EU, which is more than construction, financial services, and retail.

The findings show a slight increase in the importance of physics-based industries since EPS’s last report on their impact, which was published in 2013. Over 2007-2010, physics-based industries contributed at least €1.25 trillion of GVA per year (except in 2009), or 11 percent of the EU total.

Gross Value Added, or GVA, is a measure of how particular industries contribute to the wider economy. In simple terms, GVA is the value of what’s produced minus what’s consumed in order to produce it. GVA is related to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in that it is a measure of economic output, but unlike GDP, it does not add taxes or deduct subsidies.

Germany leads in physics industries

The new report also found that physics-based industries produce 16 per cent of business revenue in the EU, about €4.4 trillion per year, a €1 trillion increase since 2010.

Two thirds of that revenue was generated in just four countries: Germany, the UK, France, and Italy. By far the largest share of physics industries’ revenue – 29 per cent – came from Germany, where physics-based industries accounted for more than 53.4 per cent of exports.

The UK produced 14.2 per cent of physics-based revenue, France 12.9 per cent, and Italy 10.4 per cent.

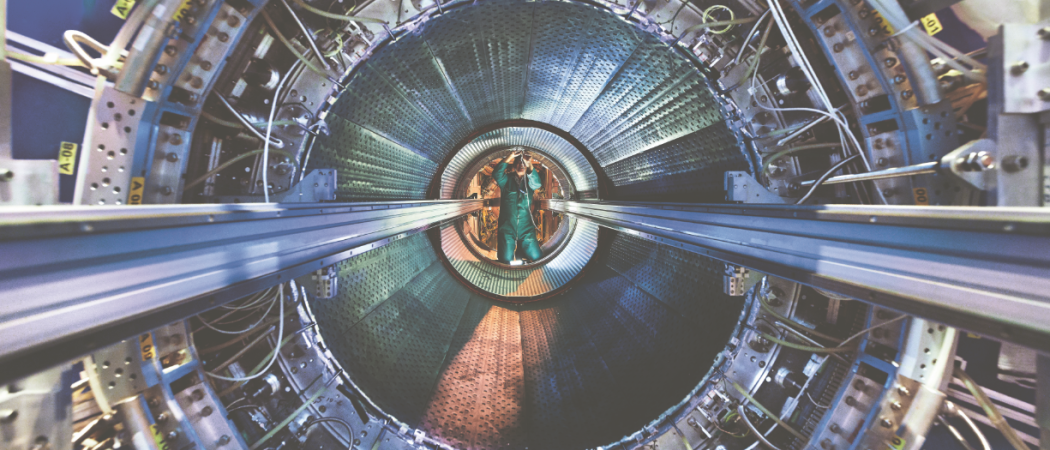

The shares for east European countries were much lower. Rudolf said she hoped to see a bigger contribution from eastern and southern Europe to the physics-based economy over the next 10 years. To that end, “EU initiatives can help in using the same kind of entrepreneurial skill training which we have seen at CERN,” she said.

Anais Rassat of CERN’s knowledge transfer office said CERN encourages its staff to develop their own ideas, which includes funding prototype development and giving them time to start their own companies.

“We have training sessions on introductions to knowledge transfer tools, and also patent information databases,” said Rassat, “it’s very important for us to create that initial link with the researchers, who might not be thinking of outside applications, because they have come to CERN to do fundamental research.”

Gabrielle Thomas, “innovation ambassador” for M Squared Lasers, a Glasgow-based photonics company, added that better design of the Commission’s online tool for finding partners in EU research grant applications could also help.

Physics employs 17.8 million people

Physics-based industries also employed 17.8 million people by 2016, which is more than 12 per cent of business employment. On average, each employee produced €90,800 per year to the economy in terms of GVA, meaning the workforce of physics-based industries is more productive than that of the manufacturing sector, where the average worker produced €60,600.

“Physicists are really a very different brand whose brain is formed to have extraordinary problem-solving skills,” said Rudolf.

The report also argues that the activities of physics-based industries cause other sectors to produce more wealth, such as when physics-based firms buy from businesses in other industries. According to the authors, this means each €1 of physics-based GVA leads to an extra €2.64 for the rest of the economy.

The EPS is a federation of physicists’ associations across 42 European countries, and is headquartered in Mulhouse, France. It was set up in 1968 to promote physicists and their field throughout Europe. The report was written for the EPS by the Centre for Economics and Business Research (Cebr), a London-based consultancy.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.