The aim is to build networks across the EU, but universities in eastern Europe say structural problems make it harder for them to get involved - and some fear it promotes brain drain

Vice rector of the University of Bucharest, Sorin Costreie. Photo: University of Bucharest

On 3 October the European Commission is due to issue a new call for the European University Initiative, with the aim of expanding the current fifty transnational networks of universities by ten. Universities in central and eastern Europe say they want to play a bigger role, but some are still struggling to become influential players in EU’s higher education sector and there are concerns the scheme promotes brain drain towards the richer member states.

As things stand, the 50 European Universities involve 430 higher education institutions across Europe. Students enrolled at one of them can earn degrees through coursework at multiple partner universities.

While heavily weighted towards partners in the EU15 countries, the initiative has attracted universities from eastern and central Europe, despite greater challenges to participating. These include the more bureaucratic internal structures of these institutions, an ingrained aversion to working together, uncertainty about long term funding for the scheme, and concerns that these networks will create a conduit for brain drain.

European Universities typically include nine partner universities that can be research institutions, universities of applied sciences, and vocational colleges. By collaborating, they aim to offer education programmes that can be completed across borders.

Students, faculty, and staff have seamless mobility between partner universities and campuses. Courses are jointly delivered, so students can complete modules of their degrees in multiple European countries.

With the coming expansion to 60 European Universities, the goal is to connect over 500 higher education institutions by 2024.

The vice rector of the University of Bucharest, Sorin Costreie, has a prime vantage point from which to study and assess this effort. Recently elected president of the Network of Universities from the Capitals of Europe (UNICA), he is also involved in his institution's membership in CIVIS, a pilot for the European Universities scheme, launched in October 2019.

“It is a major exercise in coordination and [harmonisation] among very diverse universities,” Costreie told Science|Business. “That is a major challenge, for we are talking about diverse institutions with different inner organisation and institutional culture, with different mentalities, languages, and structures of academic years,” he said.

Outside pressure removes internal friction

European Universities engage in different forms of collaboration, from agreeing joint roadmaps for research, to setting up European teaching degrees; from providing virtual citizen science hubs/knowledge bases, to formal joint supervision of PhDs.

These actions require seamless coordination. For Costreie, one of the more interesting outcomes was that the “outside integrative force caused better inner coordination”. Universities were incentivised to remove internal frictions related to teaching, research, and social engagement, so they could function better within the external network.

But collaboration is one dimension that some institutions - especially in central and eastern Europe - still struggle with. “We can still feel the shadows and phantoms of communism floating through our societies through the lack of trust and collaboration among us,” said Costreie. “Education, science, and society are based on collaboration and trust. The ‘red period’ of our common histories succeeded in increasing suspicion and mistrust.”

However, this resistance to working together has been a feature across the EU, according to Agata Lambrechts, a postdoctoral researcher at the Università della Svizzera italiana, who has closely studied how the first European Universities were formed.

“At least initially, the alliances were built primarily by institutions with pre-existing relationships,” she said. That was particularly the case for when the whole of a university was taking part, as opposed to a one or more of its faculties.

Lambrechts’ research suggested that the pilot phase of the European Universities initiative did not necessarily expand collaboration, but rather made official the “existing status hierarchies in European higher education.” For the first European Universities call, 69% of all members came from EU15 states, 23% from the newer EU countries. The remaining 8% were from non-EU countries.

The results of the latest call, announced in June 2023, continued to reflect this imbalance. Of the 262 institutions involved in the successful European University networks only 55 are from central and eastern Europe.

However, Lambrechts said, changes to the evaluation process since the pilot programme has succeeded in achieving some level of EU-wide cohesion in higher education.

Echoing this, Costreie believes one of the most valuable lessons of the European University initiative, “might be that there is no longer an east-west fundamental division - or at least that it is continuously fading.”

Universities in Widening countries are proving to be “valuable and trusty partners”, Costreie said. Their partners “may learn the enthusiasm of participating in something great, […] that will change European foundations: the enthusiasm of the lost child who is back in the family, trying to come with important and appreciated contributions.”

A channel for brain drain

Zoom in on the map of the European Universities initiative, zoom again, and then some more, and you might end up looking at the University of Petroșani in Romania. A former mining town perched between mountains, now with fewer than 40,000 inhabitants, the university was a ‘Coal Institute’ during the communist regime, later becoming a university offering degrees in mining engineering, electrical engineering and sciences.

The University of Petroșani is a member of the Eureca-Pro European University. It was here that in May 2023, researchers from another member, Universidad de León, led by María Fernández Raga, organised a workshop on brain drain. The event was intended as a forum to put forward proposals to improve brain circulation in the countries represented in Eureca-Pro.

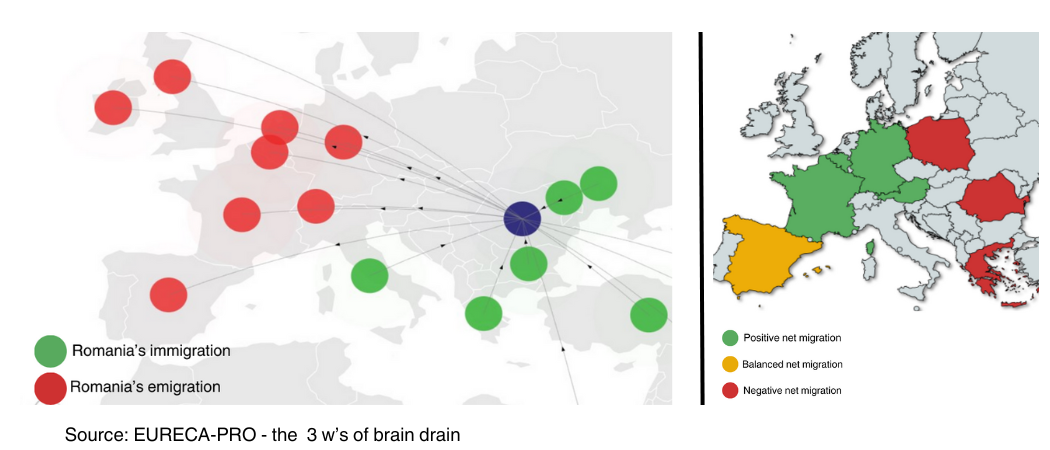

A colour-coded map of the alliance plotting talent migration shows France, Belgium, Germany, and Austria as net gainers of talent (in green), while Poland, Romania, and Greece are net losers negative (in red). As María Fernández Raga and her colleagues note, “The receiving countries are strong in research investment,” and this appears to be one of the driving factors in brain gain.

When plotted on a map of Europe, the flow of Romanian brainpower is almost perfectly divided down the middle: red on the left, indicating the outflow of Romanian talent to the west, and green on the right, indicating an inflow of talent from countries including Moldova, Ukraine, Turkey and – surprisingly - Italy.

Research presented to the European Parliament's Committee on Culture and Education in January 2023, said that for some politicians, the European University initiative may be viewed as "an instrument for brain drain towards the richer member states."

Two tier system

From 2021 – 2027 the European Universities scheme has funding of €1.1 billion. Each alliance gets up to €14.4 million over four years, causing concerns about the long-term viability of European Universities when the EU money runs out. According to research conducted for the European Parliament, funding remains one of the most significant challenges facing European Universities.

There may be discrepancies and inequalities among partners in different countries because the level of alternative financial support from public sources varies widely.

While the governments of some member states, such as Malta, provide no national funding for European Universities, others, like Bulgaria, Greece, France, and Portugal, provide direct funding. Meanwhile, Denmark, Estonia and Ireland provide only indirect financial support, for example through performance-based funding that rewards internationalisation.

In the case of Romania, the government provides both direct and indirect support to the country's 17 universities that together enroll roughly half of all Romanian students. Rector Marilen Gabriel Pirtea from the West University of Timișoara, a member of the Unita European University, says the Ministry of Education has allotted annual co-funding, indicating it understands the transformative potential of Romania’s participation in the European University initiative. Pirtea is also a member of the Romanian Parliament.

In addition to government funding, Unita and other alliances like it "have developed complementary actions and projects, financed by their own funds, or through other funding lines accessed by the consortium, in order to strengthen the alliance and its objectives," said Pirtea.

In the case of Unita, the member universities have also set up a single legal entity, the European Academic Interest Group. But he said, “That these alliances should continue to exist is not debatable, but how they will do so will prove interesting.”

Costreie points out another potential problem, which is that the initiative will create a two tier system. "The majority of European universities are not and will not be a part of the European University initiative. They won’t benefit from the attention of the European Commission anymore. Are we going to develop a new division within academic Europe?”

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.