Brexit Britain has no shortage (yet) of commercial ideas in its universities, nor of venture funding. But the talent pool for academic start-ups is shrinking

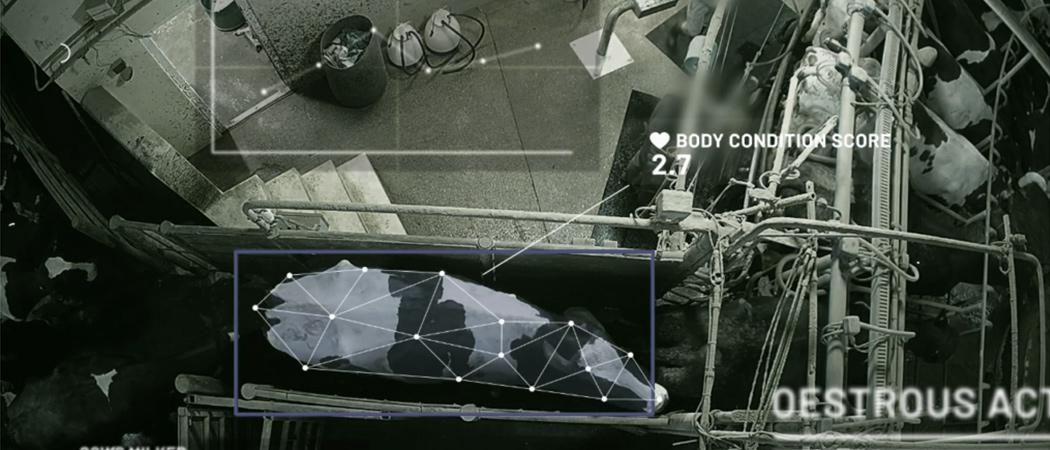

CattleEye’s video analytics, powered by deep learning AI. Photo: CattleEye

The Brexit effect is easy to see in UK universities. A continuing failure to agree UK association with the Horizon Europe research programme has put eligibility to conduct EU-funded research in the UK in a precarious position, undermining international collaborations and prompting some academics to relocate to the mainland.

With a pipeline of previously funded research continuing to feed through the system, the effects have yet to be felt in university tech transfer offices. However, there is a concern that being cut off from EU research programmes will eventually cause problems here as well.

“In the long term, if we don’t do something about the way we collaborate with Europe and access European funds, then that could have a long-term impact,” said Iain Thomas, head of life sciences at Cambridge Enterprise, Cambridge University’s technology transfer arm. “Right now, that is hitting hard in terms of bringing funds into academic research, but the effects for spin-outs will be downstream.”

Anne Lane, chief executive of University College London’s tech transfer division, UCL Business agrees. “Our pipeline comes from the university, and whatever affects that pipeline will inevitably affect us, but not for perhaps for two to five years,” she said. “But I am concerned about the Horizon programme, and whatever backstop the government puts in place - if it does put something in place - if there is a big drop in collaborative funding, that will have significant knock-on effects for us.”

Losing the EIC

The more immediate pinch point for UK tech transfer is the loss of the European Innovation Council (EIC) support to help researchers prove, demonstrate and then commercialise their inventions.

There is already a good deal of pain for recent recipients of EIC grants. As one case in point, Belfast-based CattleEye was among the latest start-ups selected by the EIC’s Accelerator programme, and is eligible for up to €2.5 million to further develop its machine learning system for monitoring the health of farm animals. But it will only be able to collect the money if the UK associates with Horizon Europe.

“As things stand, we can only get so far in the EIC contract negotiation process and won’t receive the final legal contract from the EU, although we are continuing with the negotiation stages up until then,” said Terry Canning, co-founder and chief executive of CattleEye. “I know of another UK company that was notified that they won EIC Accelerator funding six months ago, and it is still stuck in the process.”

If attempts to associate with Horizon Europe are finally abandoned, the UK government has said it will support EIC who are winners left hanging, but the details of that backstop via UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) have yet to be worked out.

Fringe benefits

These details matter, Canning noted. “One of the great advantages of the EIC Accelerator is that the company usually gets around 55% of the grant support in an up-front payment, which is brilliant for a cash hungry start-up,” he said. “With typical UKRI funding, the grant is claimed quarterly in arrears. So, we don’t know if the UKRI backstop funding will attempt to replicate the EIC funding process. If not, we will need to raise further investment.”

The backstop is also likely to lack the fringe benefits of EU support. “The great thing with any of this European funding is you get access into networks of European venture capitalists, academia, and potential routes to market in the region, so it’s hard to see how the UK government could replicate this.”

The long-term impact of losing EIC backing on academic research commercialisation is harder to determine. “In places like Cambridge there will be very little impact,” Thomas said. “In others, where there isn’t such a significant culture of [research] translation, it may be much more problematic.”

His lack of remorse over EIC funding is down to the conditions that come with it, which do not suit the way academic institutions in the UK prefer to work. “It’s constrained money, it doesn’t pay the full economic cost, and if it can be replaced, maybe that’s a good thing. The downside would be the loss of interconnectedness with Europe,” said Thomas.

Venture funding

When it comes to venture funding, it had been feared that Brexit might make it harder for university start-ups to raise money. And while there has been a Brexit effect, British institutions have stepped in to fill the gaps.

The UCL Technology Fund, for example, had been supported by the European Investment Fund before Brexit, but it could not invest in the second fund, which closed this year. “British Business Bank stepped in to fill that space, but if it hadn’t then we would have been in quite a difficult situation,” Lane said.

Other sources of venture capital have also varied. “There is probably less European venture capital money coming into our system,” she said. “That may be down to Brexit, but the European tech ecosystem has also developed, so I think they are looking at investing more in their own countries, rather than companies in the UK.”

But there has been no reticence from US venture capitalists. “They view European companies, including those in the UK, as much better value than companies in the US, which are seen as over-valued,” said Lane. UCL spin-outs such as TenPoint Therapeutics and Quell Therapeutics both raised money successfully last year, drawing on funds from the US as well as the UK and mainland Europe. “So, Brexit is not putting the investors off.”

Less talent in the pool

But in addition to a great idea and resources to develop it, start-ups need talented staff. And this is where Thomas sees a distinct Brexit effect. “When I hire into my team, I have way fewer European applicants,” he said. “And that is broadly negative, because you want to have a good applicant pool. These are difficult jobs, and you want to have people who have a certain talent and interest to do them, even if there are better salaries in other sectors.”

He sees a similar effect in start-ups, at all levels of recruitment, from people with just a few years industrial experience to more senior roles. “The problem is that it is now less attractive to work in Britain. Europeans have lost their higher [immigration] status, and although they are now no lower in status than people from elsewhere, a lot of them don’t feel that Britain is a place they want to be any longer.”

Lane’s experience is the same. “The predicted exit from the Horizon Europe programme has had an impact, in terms of making EU workers reluctant to come here, and there is evidence of that from what we are seeing with some of our spin-outs.” However, labour shortages and recruitment are an issue elsewhere in Europe and the US, so the effect may not all be down to Brexit. “It is probably a mix of the two, but it does seem as if individuals from the EU are more reticent to come to the UK than they might have been previously,” Lane said.

Brexit dividend

As far as the UK government is concerned, Brexit presents opportunities to strike new trade deals and break away from European regulations, and that may also benefit academic start-ups. For example, setting up clinical trials and getting drug approvals in the UK may become faster if the system for rapid set up of large scale, multi-centre clinical studies and accelerated regulatory reviews seen with COVID-19 vaccines and antivirals does become routine, as the government has said it intends should happen.

That may not help start-ups get to their main markets any sooner, since approval in the US or EU will still be a strategic and commercial necessity, but an early endorsement in the UK could send a useful signal. “Getting approval, or even just being slated to get a drug reviewed, can make a huge difference to the value of a company and investment interest,” Lane said.

Then there is gene editing, where the UK is changing regulations around commercialisation of gene edited crop plants. This will bring parts of the UK (Scotland and Wales do not support the move), into line with major economies such as the US, India and China, while the EU is only just beginning to engage with the issue.

Some start-ups in this area are already looking at a move to the UK because of the regulatory change, and it may also benefit future start-ups. “I think it’s important that anyone should be able to do gene editing, so therefore it is good that we can do it,” said Thomas. “Whether we can capitalise on that is unclear. But if you aren’t allowed to do it, then you can’t capitalise on it at all, so that has got to be a good thing.”

Elsewhere in the Ecosystem…

- The lack of a grace period in the European Patent Convention (EPC) is stopping some universities from commercialising their research, according to a survey carried out by the European Patent Office. A grace period would allow prior disclosure of an invention, for instance in a scientific publication or conference paper, without undermining its novelty. The survey estimates that 7.8% of applications from European universities over the past three years were prevented by a pre-filing disclosure. Where this happened, 71% of universities reported that further development or commercialisation of the invention stopped. Overall, however, the survey gives little support for the introduction of a grace period, indicating that only 6% of all users of the EPC would take advantage of such a mechanism.

- EPFL Innovation Park is expanding to a new site, with the aim of doubling its capacity over the next decade, to meet demand from start-ups emerging from the Ecole polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL). The park is currently home to over 150 start-ups and 30 large companies, spread over 55,000m². The new site, called Ecotope, will be one kilometre from the Innovation Park, with a clean transport system linking the two. Construction will begin in 2023.

- French microprocessor company SiPearl is the first start-up to get its equity funding from the European Innovation Council’s Accelerator programme. EIC equity investments were delayed because of an administrative snarl-up at the European Commission. On top of a €2.5 million grant, SiPearl will now collect €15 million in equity to help it develop and scale-up its chip technology. The company expects the EIC money to catalyse more than €100 million from other investors. The company is a spin out from the European Processor Initiative, which aims to develop a high-performance, low-power microprocessor for European exascale supercomputers.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.