Academics mourn losing principal investigator status in the teams they created. The failure to agree UK association has left consortia scrambling to rescue projects, resulting in months of paperwork and delays

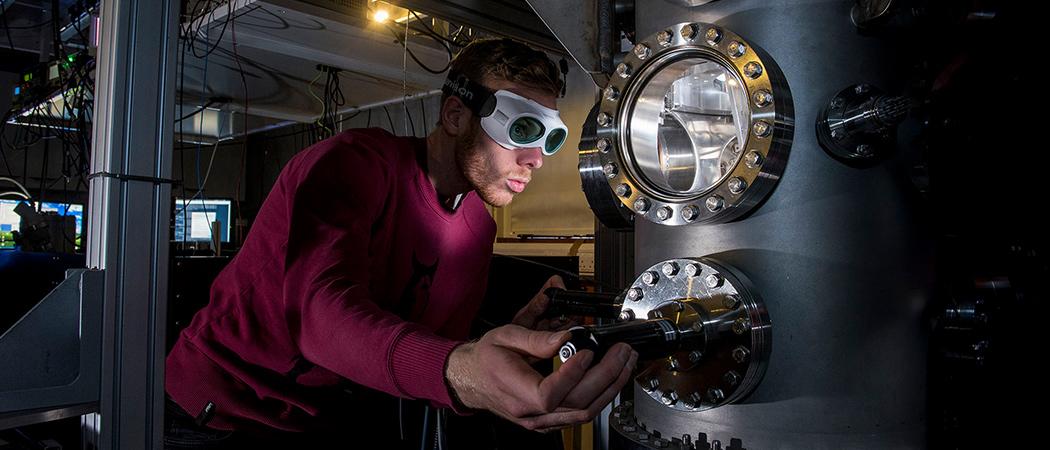

Southampton University. Photo: www.phys.soton.ac.uk/

At least half a dozen UK-based researchers have already lost coordination roles in Horizon Europe consortia because of the failure of Brussels and London to agree UK association to the programme, with the true tally losing out on leadership positions likely much higher.

The prestigious role of leading Europe-wide teams of scientists is now all but closed off to UK researchers, despite a UK guarantee scheme that tries to replicate other aspects of staying associated to Horizon Europe.

Replacing UK-based coordinators has caused enormous bureaucratic stress, forcing teams to work for months to rescue projects by drafting in new leaders and partners, and delaying the start of research.

In at least one case, an entire project fell through because it did not meet eligibility criteria because the UK is still not associated, said Peter Mason, who leads global research and innovation policy and Universities UK.

Mason said his organisation was aware of seven projects where the UK partner has been booted off its coordination role. “But I’m sure there are many more,” he said.

Under Horizon rules, partners from non-associated countries like the UK cannot lead consortia, the industrial and research partnerships that make up the bulk of the framework programme’s budget, except in exceptional circumstances where the EU thinks they are essential.

They also need to stump up their own cash to join projects, which the UK has promised to backstop. What’s more, standard consortia need at least three partners from EU or association countries, meaning extra partners are sometimes needed to make up the numbers, as the UK doesn’t count.

Working through Christmas

Hendrik Ulbricht, a quantum physicist at Southampton University, was set to coordinate a project to use levitated particles to create hyper-sensitive gravity sensors. The idea is that these ultra-accurate instruments will be used to detect large masses underground, like oil deposits, for example.

His team successfully bid for a European Innovation Council Pathfinder grant in the spring of 2021, when it seemed like UK association to Horizon was a mere formality, having been agreed as part of a wider Brexit deal the previous year.

“I was the principal investigator. I was the one who basically put the consortium together,” he said.

But around Christmas of 2021, when UK association was starting to look in doubt, Ulbricht and his team were told by the Commission that he could no longer lead the project.

It took him and 5-10 other researchers around a month of work each to “rescue” the project, he estimates.

They had to redesign and re-budget it under a different lead, bring in another partner from Germany, and apply for money from the UK government under the country’s backup scheme. “I couldn’t do holiday. I couldn’t do a proper Christmas,” he said.

Still waiting on money

For Ulbricht personally, not being able to lead the project he put together means a loss of prestige, and the experience that comes with managing such a challenging, multi-country endeavour.

And when tough scientific decisions come up during the project, Ulbricht will now ultimately have to defer to his Italian counterparts, who have taken over coordination.

“I was really looking forward to getting this together,” he said.

The UK-based academics taking part now won’t be required to do regular assessment reports and meetings, because they aren’t based in an associated country, but their colleagues in Germany and Italy will.

This lack of bureaucracy might sound like a dream come true for a scientist, but these separate rules are actually “quite odd”, said Ulbricht. “We will still work together, but it's now like a parallel universe,” he said.

Ulbricht’s team has applied to the UK’s own guarantee scheme to secure its share of the funding, but have still not yet received any money, and been forced to delay the project start six months until October 2022.

A dramatic loss

Carsten Welsch, head of the physics department at Liverpool University, was set to lead a Europe-wide network of Marie Skłodowska-Curie fellowships – until the stalemate over association meant that Liverpool lost its coordinating role.

“The fact that we cannot be coordinator anymore as an institution is a dramatic loss,” he said.

“The research can probably happen as planned. But then as the coordinating institution, Liverpool would normally be in the spotlight,” he said. “And that, of course, is something that money can't buy.”

Liverpool can of course still remain part of the network. But it can’t now host Marie Skłodowska-Curie fellows because the UK remains non-associated. It plans instead to use UK guarantee money to fund two fellowships of its own with an equivalent salary.

But these doctoral candidates won’t be able to call themselves Marie Skłodowska-Curie fellows – meaning a slightly less sparkly CV - and they won’t be able to attend networking events exclusively for the EU-funded fellows. “The prestige is clearly not the same,” said Welsch.

For both Ulbricht and Welsch, it’s been a personal blow to lose leadership over a brainchild.

“The whole experience has been quite, quite disappointing,” said Welsch. “Fundamentally, I wrote the entire proposal, I wrote the research project on behalf of partners. As coordinator, you know every bit of that project.”

Blame game

UK association to Horizon Europe looks increasingly unlikely. UK science minister George Freeman declared yesterday in Brussels that the country would launch its own “Plan B” alternative in “autumn” unless the Commission drops its opposition to UK association.

Brussels has refused to sign off on association due to its wider unhappiness with London over the Northern Ireland Protocol, which the UK is planning to override.

Freeman’s Plan B could include money for UK researchers to continue to join Horizon consortia. But can’t bring back the prestige and experience of leading these pan-European networks.

If the UK does ditch its bid to join Horizon after the summer, an almighty blame game is expected over which side is responsible for such an act of scientific mutual destruction.

For Ulbricht and Welsch, the scientists caught in the firing line, the UK is the bigger culprit.

“I don't know who to blame. It's a complicated thing,” Ulbricht said. But he added, “I'm a European, and one partner dropped out of the EU. I think they have to live with the consequences.”

“The UK government continues to play with the idea of […] breaking international law, and running away from treaties that they themselves have negotiated and signed,” said Welsch.

“And clearly, the EU has my full understanding that they are not prepared to open a flagship science programme, which is probably the most successful in the world, to a country that at the moment, they cannot trust.”

This article has been amended to make clear that the Marie Skłodowska-Curie fellows in Liverpool's network are doctoral candidates, not postdocs.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.