As the EU’s 10-year graphene flagship project comes to an end, spin-offs and other start-ups in its orbit give their verdict on its achievements and look to maintaining momentum - as they search for continuing support

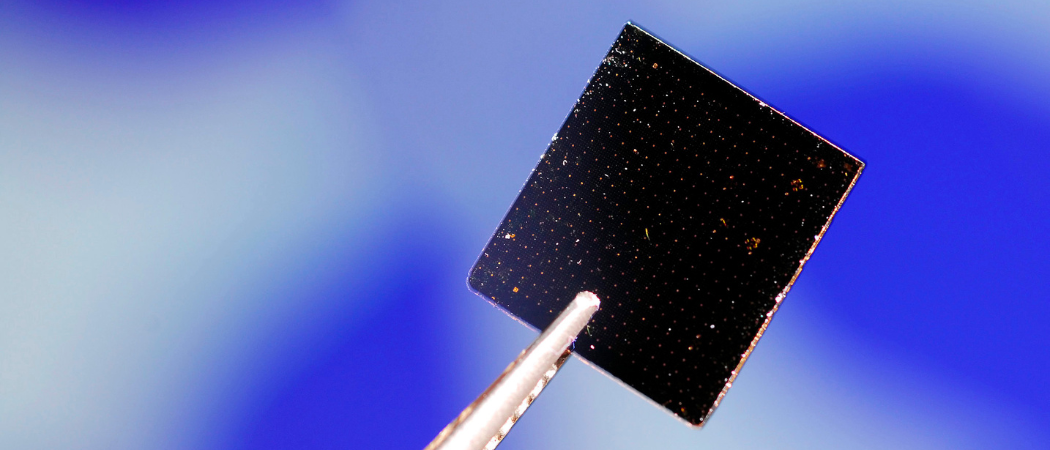

Graphene is the thinnest material ever discovered. Photo: Charles van Meter / Flickr

The EU’s €1 billion Graphene Flagship project is 10 years old, which means it has formally run its course. Taking stock last week, the project’s leaders emphasised its achievements.

“At last count we had 83 patents, and we have well over 5,000 publications, which have been cited almost 300,000 times,” said the director Jari Kinaret, of Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden. “We have a little more than 100 products on the market, and we have launched 17 spin-off companies.”

These spin-offs have attracted around €130 million in private funding. “If you put that in relation to the €400 million that the Commission has invested, you can perhaps call it a 30% return on investment,” Kinaret said.

The end of the graphene flagship means that these spin-off companies, and other start-ups that have developed in its orbit, are now looking for continuing support as they progress to the market. The challenges they single out include a lack of business experience in their own teams, a shortage of high-quality industrial infrastructure, and investor scepticism after graphene’s early hype as a wonder material.

Graphene was discovered in 2004 by Andre Geim and Kostya Novoselov at Manchester University, work which earned them the Nobel prize for Physics in 2010. The substance consists of a single layer of carbon atoms, arranged in a hexagonal lattice. It is the thinnest material ever discovered, and also the strongest. It conducts heat better than any other known material, and electricity as well as copper. It is almost transparent, yet so dense that it is impervious to gases.

These characteristics suggest a multitude of possible applications. The graphene flagship was established to help academia and industry in Europe collaborate on R&D to explore these possibilities, and then begin commercialisation.

The project was one of two Future and Emerging Technologies (FET) projects launched in 2013, each with a total budget of €1 billion. Half was to come from EU research funds – Framework 7 and then Horizon 2020 – and half from national governments. The other winner, the Human Brain Project, set out to gain an in-depth understanding of the complex structure and function of the human brain.

To date, the graphene flagship has spent €400 million of its €500 million EU allocation. It has over 170 partners from 22 countries, evenly split between companies and universities and research institutes. It also has around 100 associate members, who work closely with the Flagship but do not get EU funding.

Its research has been carried out though 15 scientific and technological work packages, covering a wide range of topics, from fundamental materials science to work on photonics, electronics and energy applications, through to production technologies and studies of graphene’s health and environmental impacts. These have been complemented by 11 spearhead projects, led by industry and focused on technologies such as air and water filtration, solar panels, electric vehicle batteries and image sensing.

Finally, the flagship has launched a 2D experimental pilot line, to support the scaling up of electronic and photonic component production.

From the Flagship to the market

The route to commercialisation often runs through the spearhead projects. For example, the circuit breaker spearhead has developed a grease-free, maintenance-free, low-voltage circuit breaker for use in the electricity grid.

“Without the flagship connecting us with the right partners, this would not have been possible,” said Anna Andersson of ABB, which is leading the project together with start-ups Nanesa and Graphmatech.

More applications for this technology are likely to follow. “Grease lubrication in mechanical drive systems is common in many devices, so if we can show this works in one product, there is a lot of opportunity to apply this concept to other types of products,” Andersson said.

ABB is now taking this technology forward, together with Nanesa, and aims to put the first maintenance-free circuit breaker on the market.

The other commercialisation route has been through the flagship’s spin-off companies, which have developed both graphene production methods and applications. While the impetus to create companies usually came from the researchers themselves, the flagship provided important connections, for example to corporate partners.

“The flagship was a catalyst,” said Ali Shaygan Nia of Dresden University of Technology, one of the flagship’s business developers. “There were more than 200 partners, including big companies, and the scientists who found opportunities to create spin-offs were in contact with these big companies from the beginning.”

This familiarity made it easier to build collaborations and other business relationships. “A degree of trust is already there in the flagship,” Shaygan Nia said. “The big corporates involved, such as VARTA, BASF and Airbus, know that these people want to do the job and are trusted.”

Inbrain Neuroelectronics is one of the 17 spin-offs. Created in 2020 by researchers from the Catalan Institute of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology (ICN2) and the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies (ICREA), the company’s goal is to develop a high-density, high-resolution graphene-based neural platform to optimise the treatment of neural disorders. These include Parkinson's, epilepsy and speech impairments.

It has also founded a subsidiary named Innervia Bioelectronics, which is focused on a collaboration with Merck in the development of bioelectronic therapies for peripheral nerve disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis.

After licensing the underlying technology to Inbrain, the flagship has continued to support the company. “We could not have developed without the flagship,” said Carolina Aguilar, its co-founder and chief executive. “It’s this kind of coordinated research and other activities, on a large scale, that produces meaningful results.”

In particular, Inbrain was able to draw on flagship research into the biocompatibility and toxicity of graphene, along with work characterising the material and setting standards. “The fact that there were different work packages looking at the development of graphene from different angles has made it possible for this material to succeed commercially,” said Aguilar.

The graphene flagship has also benefited companies that emerged independent of its research. This includes Swedish start-up Grafren, which was established in 2018 by two researchers from Linköping University to develop applications for graphene-coated fibres.

“We are not a spin-off from any research carried out by the Flagship, but we were always in its outer orbit, and we have benefited from the knowledge that it has generated,” said Erik Khranovskyy, Grafren’s founder and chief executive.

In particular, the flagship has made a significant contribution to establishing supplies of good quality graphene in Europe. This is something companies can then build on. “The job of making and characterising the material has already been done, mostly by the Graphene Flagship,” Khranovskyy said, adding that most of Grafren’s suppliers are spin-offs from the project.

Foundational phase

Both of these start-ups are confident that the conclusion of the graphene flagship project does not leave a gap in the ecosystem. “We’ve completed the foundational phase, which has allowed us to stand on our own feet, and now the graphene flagship is transforming into a group of consortia for industry,” Aguilar said.

For example, a 2D Materials Innovation Consortium is being established to bring together graphene companies that have made it to a commercial stage.

“The important thing is that we continue to share the results of our work and bridge the gaps that are there at industry level,” said Aguilar. These include further work on standards, benchmarking, and safety. “We have to keep sharing this information, and the consortium should allow that to happen.”

Shaygan Nia thinks that the relationships forged in the flagship will endure. “Of course, if you let the project run there would be more results, but stopping it doesn’t mean that the collaborations stop,” he said.

However, governments and the EU still need to pay attention to the sector. “I believe that some of the spin-offs will survive easily, but for others the future is less certain,” he said. “We have a financial crisis now. They will have to find investors, and the EU and national governments should support them.”

Khranovskyy also sees commercialisation as the next challenge. “For that to happen, we have to support the next stages, for example with a business incubator specifically for graphene companies,” he said.

Most of the flagship spin-outs are still run by the researchers who founded them, and will need help to get to the next stage. “It’s important to attract the right kind of business minds who can sell the products in the right way, and demonstrate the value of graphene to customers.”

Getting people with this kind of business experience into graphene start-ups will be the first test for the industry. “Before we can sell graphene value to corporate customers, we have to sell the idea to business minds, and convince them to join us,” Khranovskyy said.

For Aguilar, an important part of the scaling up challenge is the quality of industrial infrastructure. “There are many facilities in Europe that could help everybody to scale, but they need the right quality management systems and certifications, and sometimes this has not been a priority,” she said.

Further support EU in this respect would be valuable. “If we want to make it to market at the highest scale, we need to bridge the industrialisation gap and certify clean rooms and other infrastructure with the right ISO standards for commercialisation,” Aguilar said. “That means allocating resources for putting those quality standards for manufacturability in place,” Aguilar said.

Khranovskyy singles out a number of other challenges. One is a continued suspicion about the safety of nanomaterials, including graphene, an issue that was already being addressed through the flagship’s SafeGraph project. Awareness also needs to be raised about the economics of graphene. “We need to communicate that graphene is no longer expensive,” said Khranovskyy.

Finally, there is an investment problem, thanks in part to the early hype around graphene’s commercial prospects. “Some of the early companies failed within a few years, and that created a scepticism for next 10-12 years,” said Khranovskyy. “Now it is better, but we would benefit from a more direct mechanism to match graphene companies with investors, or even support them directly.”

In addition to using mechanisms such as European Innovation Council grants, he would like to see targeted support for graphene companies. “This will inspire other private and venture investors to join the wave,” he said.

While the graphene flagship is now formally over and its leader is off to pastures new – Kinaret is to be chief executive of the EU’s Key Digital Technologies Joint Undertaking – European money is still flowing into the field. Horizon Europe is supporting further research and innovation activities, and Chalmers is running a three-year coordinating and supporting action for the field.

“We have 118 partners and counting for these projects, approximately balanced between academia and industry,” said Patrik Johansson, vice director of the graphene flagship. “We also have approximately 60% fresh blood, which is to say industry and academia that has not previously been involved in the graphene flagship. So, there has been a renewal.”

Elsewhere in the Ecosystem…

- The European Commission has unveiled the first cohort of projects going into the European Blockchain Sandbox, a project that allows start-ups and other innovative companies to test blockchain applications, and explore how regulators might look on them. The 20 use-cases range from logistics support systems to notary services, from carbon tracking to car battery passports.

- Spanish wind propulsion start-up bound4blue has closed a €15.9 million Series A funding round, led by GTT Strategic Ventures, with the participation of the European Innovation Council Fund and a range of other investors. Founded in 2014, the company has developed a system of rigid sails that can be retrofitted to ships such as tankers, ferries and cargo vessels, reducing fuel consumption and improving environmental impact.

- Ascento, a student start-up from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH Zurich), has raised $4.3 million in pre-seed funding to further develop its security robots. It has also unveiled its latest autonomous outdoor security patrolling robot, called Ascento Guard. The funding round was led by Wingman Venture and Playfair, and includes support from the Swiss Innovation Agency Innosuisse and the European Space Agency incubator in Switzerland.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.