Brussels should aim to increase the dependence of other powers on the EU, not just reduce its own dependencies. This means investing to stay ahead where it dominates key parts of supply chains

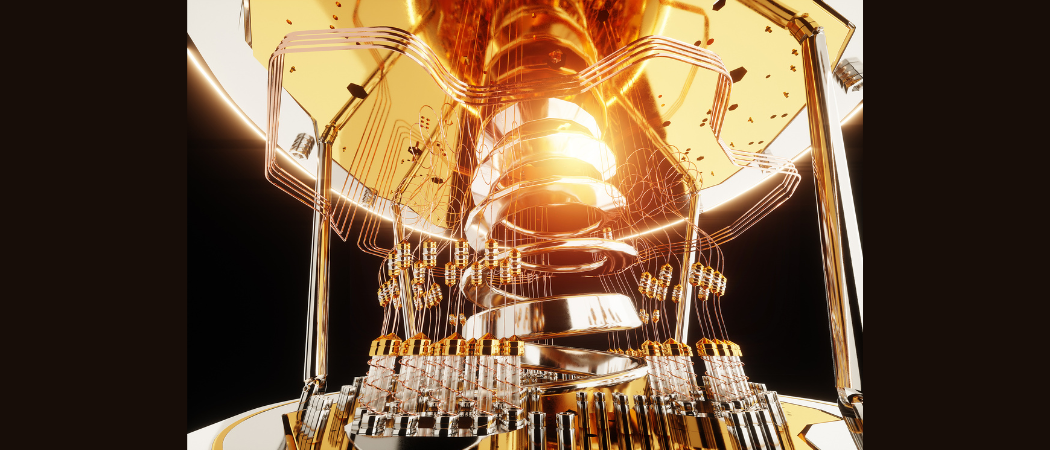

An illustration of a quantum computer mixing chamber. The EU is in a position to lead on some - but not all - aspects of quantum technology

The EU must retain its lead in key parts of technology supply chains as a way of gaining geopolitical leverage over other powers like China, according to a new analysis by the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR).

So far, Brussels’ approach has largely been to “de-risk” relations with countries like China, by trying to create alternative sources of rare earth magnets, for example, a sector that Beijing dominates.

However, alongside this, the EU must ensure it stays ahead in specific technologies where it still has a lead, to provide Brussels with clout when dealing with rival powers.

Europe should “maintain and increase other countries’ dependencies on the EU for certain key technologies,” argue Tobias Gehrke and Julian Ringhof, both policy fellows at the ECFR.

They are not arguing for the EU to try to dominate entire sectors like semiconductors or quantum technologies. This is neither “realistic nor desirable” and would be to throw money into a “counter-productive subsidy race”.

Instead, the EU needs to drill down into technology supply chains to find where it is still indispensable to the global economy – and make sure it stays ahead.

For example, within quantum technologies, speciality lenses and lasers, adhesives, cooling systems, and single-photon detectors are areas where the EU could develop a technological “edge”, rather than try to dominate the entire quantum sector.

Similarly, while Europe is a “minnow” in the mining industry, EU companies boast some of the world’s most cutting-edge mining and recycling equipment.

There’s also the well-known example of ASML, the Dutch company that provides advanced semiconductor lithography machines, which are critical to producing the world’s most advanced chips. They are so complex and specialised that it is “close to impossible” to replace them, at least in the medium term, making them an “enormously powerful edge.”

As part of the growing technological rivalry between the west and China, ASML stopped shipping its most advanced machines to the country in 2019.

The first step is to identify where Europe still has an edge. The Netherlands and Germany have started gathering this kind of information.

“However, the industrial intelligence gathered by national governments on domestic positions cannot produce a complete picture of the EU’s strengths and weaknesses.” A common EU approach is needed, the authors say.

Brussels has started identifying key dual-use technologies as part of an economic security strategy. But the authors argue the criteria the Commission is using don’t extend far enough.

The second step is “targeted investments and protective measures” to maintain the EU’s technological edge. Japan has already taken a similar approach, they point out, funding companies that manufacture “niche materials and tools” that are indispensable to the semiconductor industry.

Last week, Commission president Ursula von der Leyen used similar language in her annual – and possibly last – state of the union address. She promised “common European funding” to preserve a “European edge on critical and emerging technologies” through the Strategic Technologies for Europe Platform (STEP) platform.

“With STEP we can boost, leverage and steer EU funds to invest in everything from microelectronics to quantum computing and AI,” she said.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.