Both the US and EU are trying to rebuild their chipmaking industries after years of dependence on east Asia. But retraining will be slow, and immigration reform may be a quicker solution

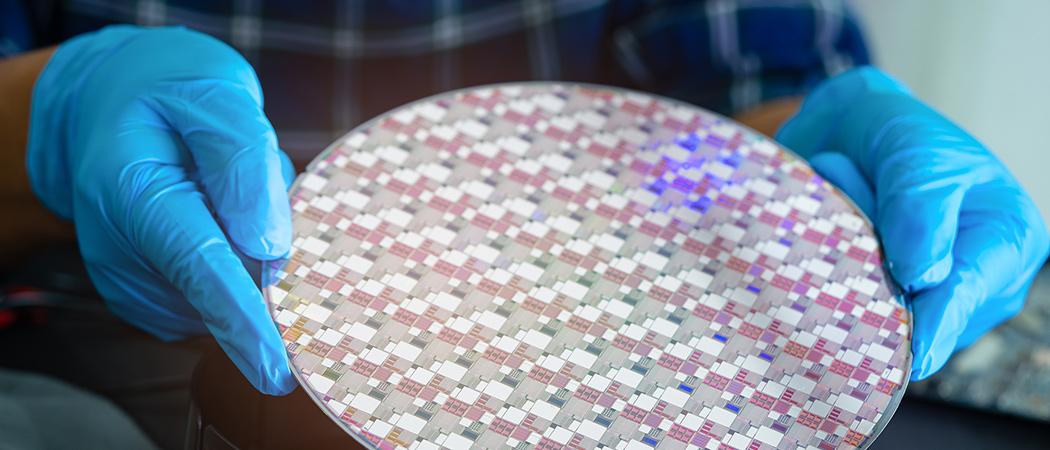

Silicon wafer for manufacturing semiconductors

Lawmakers in the US have proposed legislation to help universities train a new generation of semiconductor workers as a global “war for talent” threatens ambitious plans in the US and EU to end east Asian dominance of chipmaking.

Chip plants in the US are behind schedule because of workforce shortages, and even in Taiwan, the global leader in semiconductors, there is a labour squeeze.

After a global shortage of chips in 2021 that disrupted supply chains, including of European carmakers, politicians in both Brussels and Washington have unveiled plans to build up their own manufacturing capabilities and cut dependence on producers in Taiwan and South Korea.

In March, US chipmaker Intel announced an €80 billion investment in foundries and R&D centres in Germany, Ireland, Italy, Poland, Spain and France.

But without the skilled engineers and researchers to support these plants, European and American plans could falter. Earlier this year, it was reported that the first US plant of leading chipmaker Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co in Arizona was three to six months behind schedule due to labour shortages and COVID-19 infections.

What’s more, “the EU faces an even bigger uphill challenge than the US,” said Jeremy Neufeld, a fellow at the Washington DC-based Institute for Progress (IFP), a think tank hoping to speed up scientific and technology advancement.

“Chip manufacturing tends to be a winner-take-all industry and the EU is behind the US, let alone Asia,” he said. The semiconductor workforce in the EU is roughly 200,000, smaller than the US’s 300,000.

The EU also lacks the US’s leading chip design industry, which can cross-fertilise manufacturing, Neufeld pointed out.

War for talent

Romain Pierredon, a semiconductor industry research analyst at the Paris-based firm AlphaValue, said European chip companies were engaged in a “war for talent” and having to pay ever more to recruit the people they needed. “It’s an increasing burden,” he said.

To help solve this problem in the US, Republican and Democrat lawmakers last week introduced the so called Chipping In act, which would create National Science Foundation awards for universities and non-profit organisations to build more and better microelectronics programmes.

It also proposes traineeships to fund research for students who pursue microelectronics during a masters or doctoral decree. These will be focused on minority-heavy universities. The bill will also better integrate microelectronics into science, technology, engineering, and mathematics degrees.

“To remain competitive on the global stage, we must meet the demands of this growing industry by investing in a technical workforce at our colleges and universities. STEM education is the future,” said Republican representative Mike Waltz in a statement supporting the bill.

There is also a dearth of semiconductor hardware programmes at European universities, said Pierredon. “I’m not aware of any schools that have a specific semiconductor programme,” he said. Instead, the bulk of this “niche” education is happening in Asian countries like Taiwan, South Korea and Singapore.

The proposed European Chips Act, launched earlier this year to boost the EU’s global share of semiconductor production to 20% by the end of the decade, does have a focus on training and attracting talent. “The EU has a limited pool of talent, and lacks a workforce with the necessary skills,” says a working document on the act.

Brussels’ solution is a network of “competence centres” across the EU to train new staff and upskill existing workers.

Separately, in 2020 the EU launched a ‘Pact for Skills’, a partnership among companies, public bodies and other organisations to bolster lifelong learning and anticipate what skills will be needed in the future.

Immigrants needed

But critics in the US believe that immigration, in addition to more domestic training, is essential to alleviate the workforce shortage.

“Immigration reform should be part of the solution,” said Tsu-Jae King Liu, an electrical engineering professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and a board member at Intel.

Around 40% of high-skilled semiconductor workers in the US were born abroad, with India the most common origin country, followed by China, a 2020 report from the Center for Security and Emerging Technology at Georgetown University found.

“Immigration restrictions are directly at odds with U.S. efforts to secure its supply chains,” it concluded. The number of Americans in semiconductor-related graduate programmes has stagnated since 1990.

“Investing in domestic education and upskilling initiatives is definitely necessary for the long-term health of the workforce but it's a long-term strategy that will not yield dividends within the quick timeline that Congress wants new semiconductor plants to be up and running,” said the IFP’s Neufeld.

The Biden administration has so far failed to pass meaningful immigration reform that would make it easier for high-skilled workers to come to the US.

But earlier this month, lawmakers launched a new effort to speed visa processing for immigrants with a STEM doctoral degree looking to work in a “critical” industry, including semiconductors.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.