Joint research calls, supply chain monopolies and standards setting. All these topics and more were on the agenda at a meeting in Washington DC. China was shut out, opening a geopolitical fault line in a critical technology of the future

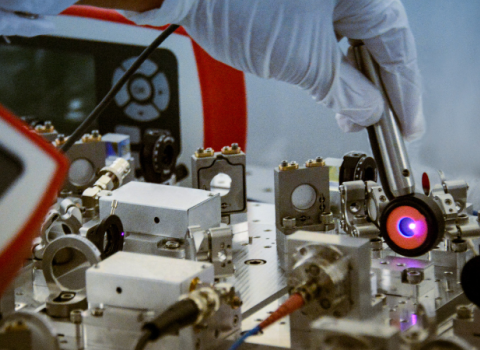

Quantum computers and accelerated discovery. Photo: IBM

European countries, the US, Canada, Australia and Japan are building a quantum technology alliance of democracies – notably excluding China from a key global forum on this critical area of research.

The most recent meeting of the group, held in Washington DC last week, discussed setting up joint research calls for quantum projects, and strategised about the risks of other countries establishing supply chain monopolies over quantum computer components.

Quantum technologies, based on the often strange laws that underpin quantum physics, promise everything from hyper-precise military sensors to a new type of computing that could revolutionise drug discovery, although some of the field’s potential remain years or decades away from becoming a reality.

The group could still expand to include other countries, but it is explicitly limited to a club of states with democratic values, opening up a geopolitical fault line in scientific research.

“We’re trying to create a trusted community with like-minded nations,” said Freeke Heijman, who represented the Netherlands at the Washington DC meeting on 5-6 May, and is co-founder of Quantum Delta NL, a body trying to build a national quantum ecosystem.

“It’s about sharing certain values that make it easier to collaborate, and we see values include things like a level playing field, fair competition, but also democratic values, privacy, things like that,” she said.

The group, which also includes Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK could still expand in the future, said Sabrina Maniscalco, professor of quantum information at the University of Helsinki, who represented Finland.

“To have certain discussions that could be really important for the national security of several countries requires to start with the so-called like-minded countries, where we have shared principles like democracy, trustworthiness, inclusion and diversity,” she said.

The countries involved want to better understand and coordinate each other’s national quantum initiatives, which have proliferated in recent years as governments have cottoned on to the potential of the field.

“There’s a need and interest to coordinate between these initiatives, to share best practices,” said Heijman. The group, which includes quantum start-up representatives as well as scientists, wants “lower barriers for ecosystems to connect,” she said.

There are also plans for the countries involved to launch join research calls. Involving all states would be “very hard” initially, Heijman said, so the plan is to start with calls by two or three countries acting together.

Supply chains for quantum computer components are also under discussion. For example, some models use the rare isotope helium-3 to cool down to ultra-low temperatures.

“One wouldn't like to see critical components of a quantum computer being only available with one supplier,” said Heijman. But she noted, no one country has a monopoly on any particular parts, as yet.

A plague of errors

Also on the agenda is standards setting in quantum technologies, for example, measuring exactly how powerful existing quantum computers truly are, given that they are still plagued by errors and noise that can confound simple measurements of power.

Another key priority is training up a workforce in such a nascent area, like engineers who can programme in new quantum languages. “Quantum computers work according to a logic which is very difference compared to classical computers,” said Maniscalco.

Quantum is sometimes spoken about as though it were a single technology. But in reality, it is a basket of often very different tools, with widely varying readiness levels.

“They are very different things,” said Maniscalco. “An expert in quantum sensing may not know anything about algorithms,” needed to programme quantum computers, she said.

Quantum sensing, which promises even more precise measurements than conventional sensors and which could for example, be crucial for jet fighters is already “very close” to commercialisation, she said.

Quantum computers, on the other hand, are distant relatives to their conventional alternatives in terms of computing power, and are plagued by noisy results. Instead of conventional bits, they contain qubits that can exist in a state between 1 and 0, potentially allowing them to model the quantum world, opening up avenues to better understand quantum chemistry and facilitate new methods of drug development.

Our existing, flawed quantum computers might start to help with industrially interesting chemistry problems in 3-5 years Maniscalco estimates. But it could take 20-30 years of improvements to quantum computers before they start having a truly “disruptive” impact, she said.

The industry is still in its infancy, and even the world’s most advanced quantum computers “can’t do anything useful” yet, said Heijman. But if the progress of AI has taught researchers anything, it was important to get out ahead of social and security problems before it is too late, she said. “[AI] rolled over us. And then you’re too late, in a way, to fix it.”

The Washington DC meeting is the largest get-together of quantum allies so far, but it is not the first. Previous meetings between smaller groups of countries took place in Paris earlier this year, and in Delft last November.

In a separate development, the French National Centre for Scientific Research announced last month that it was opening a Quantum Frontiers Lab at the Université de Sherbrooke in Quebec.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.