The EU is world-leader in quantum research, but companies set up to exploit this are struggling to get the money needed to scale. Experts say the EU and member states should coordinate efforts and work to boost investment

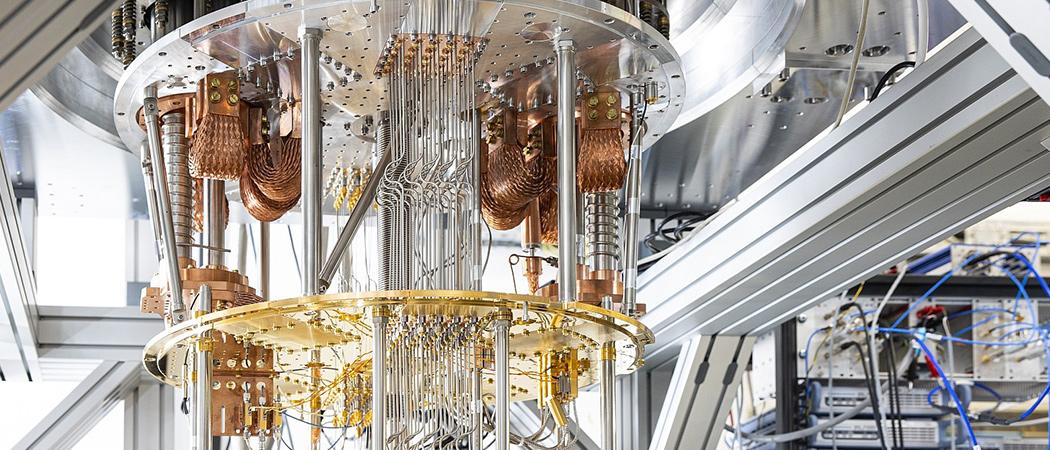

Quantum computer from the OpenSuperQ project. Photo: Forschungszentrum Jülich/Sascha Kreklau.

The 2022 Quantum Technology Monitor published by the consultants McKinsey reports that in 2019 the EU had the highest concentration of quantum technology expertise and journal papers.

The same was true for business creation based on this, with the EU home to world's largest quantum technologies industrial association, with some 150 members and over 100 start-ups active in the field.

But as these companies attempt to scale-up they are facing the brutal reality of a lack of funding. As the McKinsey data highlights, in terms of investment in quantum technology start-ups, Europe lags with $294 million invested from 2001 - 2021, while the US leads the way with $2.164 billion, the UK is second at $979 million, and Canada third at $658 million.

The picture is even more gloomy given the EU accounts for 25% of total quantum technology companies. As has been seen in other tech sectors, lots of high potential start-ups are chasing a small pool of private capital.

Besides loss of competitiveness, EU talent and start-ups are obliged to move to the US to get backing.

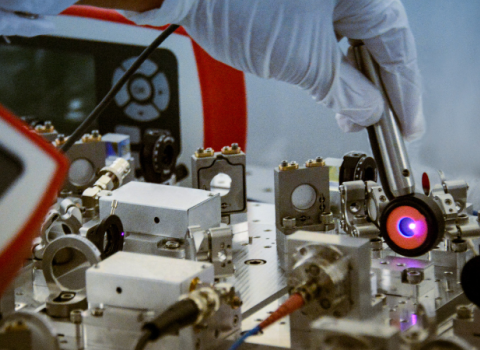

While quantum computers are not yet ready for the commercial mainstream, prototypes of other quantum technologies, such as sensors are on hand and ready for testing in different applications.

One example is the use of sensors for medical diagnostics, where it is possible to zoom in “to the level of a single neuron,” said Tommaso Calarco, director of the Institute for Quantum Control at the Jülich Research Centre, Germany. Meanwhile, in time measurement and satellite navigation, it will be possible to reach, "centimetre or millimetre precision,” he said.

The search for private investment

The potential is understood, but translating that through to commercial products is risky, and the consequent lack of private funding is a significant obstacle.

The large tech companies that are investing in quantum technologies elsewhere are almost non-existent in Europe. The same goes for venture capital firms with an interest in the sector.

US investors are showing an appetite, but notes Enrique Lizaso Olmos, founder and CEO of Multiverse Computing, a quantum software company based in San Sebastian, Spain, they may be "restricted by investment policies" and might face limitations, such as not being allowed to invest in certain European countries.

Behind all this, there is a general conception that Europe as a whole is risk averse. And as Lizaso says, the quantum field would not be the first case of the EU failing to build on its excellent science base. In the mobile sector, for example, EU companies cannot compete with giants like Apple, Android or Huawei.

But the risk-aversion argument doesn't convince everyone. Calarco believes the problem is not that EU investors have "less courage or vision", but they didn't benefit from the "huge profit margins of the Internet revolution" that enabled US counterparts to reinvest vast amounts of capital. It's a matter of, "sheer availability of cash", he said.

For Kees Eijkel, director of business development at the QuTech quantum research institute in Delft, Netherlands, it is the "limited experience" of the deep tech and quantum technology sector that is holding back significant investment.

In the EU, there remains a "long learning curve to go through to get all the experience,” Eijkel said. A good starting point might be drawing in funding and people "from other parts of the world." Sharing experiences could, "improve the learning curve" and at the same time, "decrease the risk", he said.

Support measures

The EU is implementing a number of measures to boost private investment and help European quantum technology companies to scale-up. In particular, a Commission official said, the EU is setting-up a dedicated quantum fund, encompassing various actions.

One such is allowing quantum technology start-ups to apply for the European Innovation Council’s Accelerator, which is offering companies equity financing. Another is the InvestEU programme, for which the European Investment Fund, which is currently managing €10 billion under InvestEU, is now selecting intermediaries to invest in quantum technology companies. The aim is to make investors less risk-averse by "coming in with the EU budget", the official said.

Further help could come from the European Chips Act, proposed by the Commission in February this year, with the aim of mobilising €43 billion to increase the EU's global share of semiconductor production. The act is expected to support companies in scaling-up, and this should include some aspects of quantum technologies.

In addition, the EU will be providing quantum technology companies with test beds for putting novel applications through their paces, in the Horizon Europe framework partnership’s Open testing and pilot production capabilities for quantum technologies.

This is a multi million euro project for which the Commission is currently selecting companies, "that will receive funding and access to infrastructures for their business", according to the Commission official.

There also have been moves by member states to increase national investment in quantum technologies, though the landscape is uneven. While Germany and France have announced plans to spend respectively €2 billion and €1.8 billion to support quantum research and development, Italy is now taking the first steps, using money from the pandemic Recovery fund.

More investments, more coordination

Despite these EU and member states initiatives, industry and scientists think there is still room for improvement.

For instance, Calarco said, it would be “highly effective” if the Commission’s quantum fund was able to make equity investments. Another good move, he said, would be removing the EU legal constraints that make it difficult for start-ups to take advantage of funding programmes, holding back the "flourishing of start-up ecosystems.” Similarly, restrictions on state-aid measures should be reconsidered in the case of quantum technologies, giving the sector a further boost.

Lizaso suggests the EU should be able to become a leading investor in venture capital, as is the case in Canada. Such a measure would stop US investors, who often lead funding rounds, from dictating their own terms because these are not always in line with European interests. Lizaso also said the threshold for quantum technology companies in the EIC Accelerator, should be increased to €50 million.

But the most important thing is for the EU to be nimbler in implementing its initiatives because the speed of change in deep tech sectors is "tremendous", Lizaso said.

At a national level, Calarco suggested the creation of an "overarching structure" for quantum technologies, encompassing all the ministries, in order to avoid budget and policy fragmentation.

Joining forces among member states could be equally important. Eijkel said national efforts should be "coordinated or done on the European level", enabling venture capital investors to form syndicates and work at a larger scale.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.