Act will aim to pull together disparate EU quantum research. During questioning by MEPs, Finnish candidate also backs dual use and basic research

Henna Virkkunen, commissioner-designate for tech sovereignty, security and democracy, during her confirmation hearing at the European Parliament in Brussels. Photo credits: Lukasz Kobus

The proposed commissioner for tech sovereignty, security and democracy has revealed she is cooking up a Quantum Act to pull together fragmented research efforts by member states.

Under questioning by MEPs earlier this week, Henna Virkkunen argued that quantum technologies are a European strength, but that EU legislation is needed to consolidate individual member state programmes.

Quantum is, “an area where we can be very positive and optimistic,” she said. Europe has “super talented researchers” and “top quality research” but the market is “too fragmented.”

“Many member states, they have their own quantum strategies,” she said. “Now we should have [a] more comprehensive common approach.”

In response, the EU will come up with a “quantum plan” and possibly a “quantum act” to pull researchers and resources together.

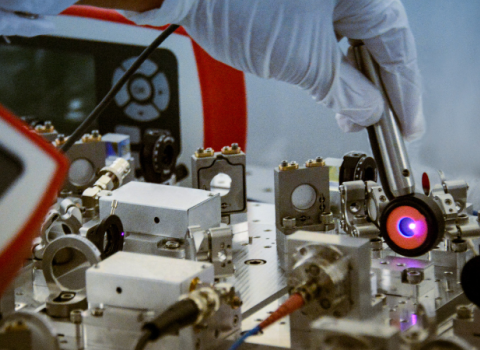

Quantum technologies span a broad range of applications, ranging from new types of computers, to sensors, all of which exploit the properties of quantum mechanics.

Virkkunen didn’t explicitly say what aspects of quantum technology she wants to boost, but later in her hearing talked of introducing a “quantum chips act”, suggesting that she primarily has quantum computing in her sights.

The proposal for an act takes up a suggestion made in September by the European Liberal Forum, a think tank affiliated to the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe parliamentary bloc, when it warned that member states are duplicating quantum computing research, not investing enough, and need big spending on quantum computing infrastructure.

“The Quantum Act would serve as a central legislative framework to unify and streamline quantum research and commercialisation efforts across the EU,” the forum said.

EU ‘a player’

It’s tricky to say with certainty which country leads the race to build quantum computers, as they are still in an early stage of development, and not yet exactly comparable like conventional supercomputers.

Noise – the extent to which faults creep into their operations – arguably matters as much as the raw number of qubits, the quantum equivalent of a computing bit.

So far, they can beat classical computers only on very narrow, artificial problems, although the hope is that one day they will be able to perform calculations that are currently impossible, like simulating quantum mechanical systems themselves.

The US companies Google and IBM have touted some of the biggest hardware advances. IBM, however, has several research centres dotted across Europe, with its Zurich base focusing on quantum, among other areas.

Germany currently ranks fourth in the world in quantum computing, as judged by the number of top 10% cited research papers, according to a recent study into the global leadership of 64 critical technologies by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), a think tank. The UK is a whisker ahead of Germany, with China second, and the US comfortably leading.

On other quantum technologies, Germany does even better, ranking third in the world for quantum sensors, and quantum communication, a field in which Austria is fifth in the world. On post-quantum cryptography, Germany ranks fourth.

The ASPI report, which was raised by MEPs during Virkkunen’s hearing, actually makes for moderately encouraging reading, describing the EU as a “competitive technological player”.

If all EU countries were aggregated, they would lead the world in two technologies - gravitational-force sensors and small satellites – and would rank second in 30 of the technology areas studied.

As it stands, China leads in 57 of the 64 domains, although as this is only a measure of highly-cited papers, it doesn’t mean Beijing has a real world advantage over the US, at least for now.

Dual use research

Virkkunen’s proposed quantum act was a rare moment of revelation during a three-hour appearance in where she otherwise stuck to tightly prepared lines, often recycling points to answer similarly repetitive questions from MEPs.

Her portfolio, covering tech sovereignty, security and democracy, is a sprawling one, and she was peppered with questions on everything from shoddy goods flooding the EU market to Chinese telecoms providers.

For the research world, she did however make a few other notable remarks, both in her hearing and in written answers released beforehand.

She appears to back an idea floated by the European Commission to allow dual use technologies funding in Framework Programme 10, the successor to the Horizon Europe research programme, which starts in 2028. Universities are overall opposed to the change.

“Most of the critical technologies of tomorrow are dual use,” Virkkunen said in her written statement. “If confirmed, I would work together with the other commissioners involved to harness the EU's dual use and civil-military potential.”

AI Factories

Virkkunen also said that pressing ahead with the Commission’s AI Factories initiative would be one of her priorities during her first 100 days in post.

The idea is to expand the EU’s network of supercomputers, and give start-ups and other firms access, in part to develop AI products.

“We are giving access to supercomputing to industry, start-ups and researchers. It’s a bottleneck,” she said. Last week, the Commission received seven proposals for AI factories, involving 15 member states, she revealed.

Despite the technology focus of her role, Virkkunen also had warm words for basic research, stressing to MEPs that it is crucial for European innovation.

“EU tech sovereignty encompasses the whole development cycle of technologies, from fundamental research to commercialisation by industry,” she said. Elsewhere in her answers to MEPs, she said the EU should “step up” its R&D spending.

Vance threats

However, it’s unlikely that the finer points of R&D spending will be her number one priority after she is installed in post.

Top of the in-tray is implementing the raft of digital legislation passed by the outgoing Commission: the AI Act, Digital Services Act (DSA) and the Digital Markets Act.

As she put it to MEPs, “my focus would be on enforcing and implementing the digital laws enacted by co-legislators so far.”

The most pressing problem is how hard to pursue charges against X, formerly Twitter, which is being investigated for deceptive design and blocking access for academic researchers.

As several MEPs noted during the hearing, X’s owner Elon Musk is now a key part of the incoming US administration of Donald Trump, making the platform a dangerous target.

Trump’s vice president JD Vance has threatened to pull out of NATO if the EU followed through on action against Musk’s X. “It’s insane that we would support a military alliance if that military alliance isn’t going to be pro free speech,” he said in September.

During Virkkunen’s hearing, Social Democrat MEP Matthias Ecke warned that this was an “inacceptable threat”.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.