The era of prescription digital health has dawned with approval of an app assessed to the same standard of clinical evidence as a conventional drug. Now pharma companies and digital therapy pioneers are forging development and marketing deals, while EU regulators and payers flounder

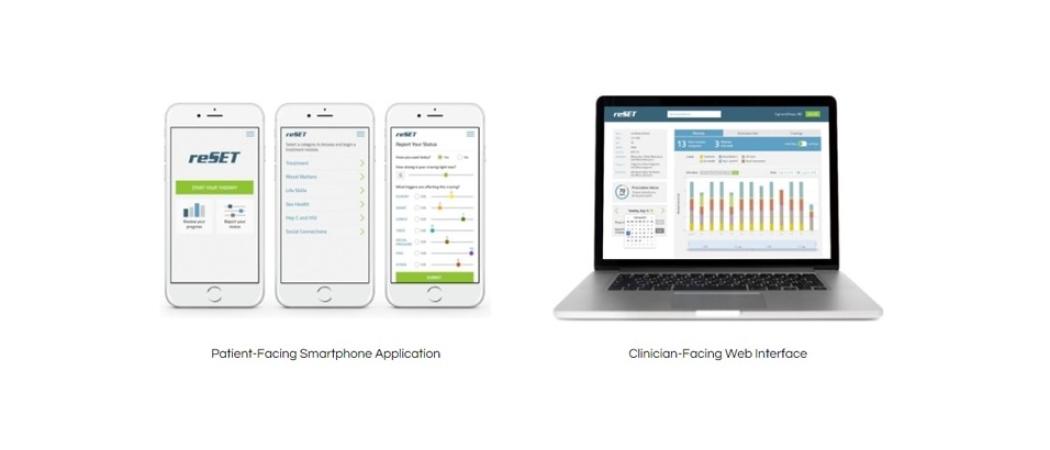

reSET, an app it has developed to treat addiction to alcohol or drugs, to the same standards of clinical evidence as traditional pharmaceuticals, developed by Pear Therapeutics.

Sensing a challenge to the established order, healthcare professionals, pharma companies, payers and regulators have to date taken a dim view of the relentless proliferation of unregulated, free to download health and wellness apps.

Now though, a new breed of approved digital therapeutics is poised to change attitudes.

The pioneer of the field is Pear Therapeutics, which lobbied a reluctant US Food & Drug Administration (FDA) to assess reSET, an app it has developed to treat addiction to alcohol or drugs, to the same standards of clinical evidence as traditional pharmaceuticals.

Last September, reSET became the first digital therapeutic to get FDA clearance, validating the regulatory pathway and sparking interest from several big pharma companies, in particular because FDA-approved digital therapeutics can be prescribed as monotherapies or in combination with drugs.

reSET is approved as a prescription-only method of providing cognitive behavioural therapy for patients who are currently enrolled in outpatient treatment under the supervision of a clinician. The app can be prescribed for a 90 day course of treatment.

In April, the Swiss pharma company Novartis announced a deal with Pear to commercialise reSET. Currently, treatment for drug addiction – for those who are able to access it – typically involves resource intensive face-to-face interactions in a specialised setting. Inconsistent quality of treatment and limited accessibility equates to poor outcomes, with low rates of abstinence and high dropout rates.

As a further indication that digital therapeutics are now entering the mainstream, a month earlier Novartis and Pear sealed an agreement to carry out joint development of digital treatments for schizophrenia and multiple sclerosis.

Under this agreement, Novartis is working with Pear to advance clinical development of Thrive, a digital therapeutic for schizophrenia, which has demonstrated potential usability, retention and preliminary efficacy in early clinical studies.

Prescription digital therapeutics will work alongside drugs to deliver superior patient outcomes, said Corey McCann, president and CEO of Pear. “We believe this collaboration further supports the clinical viability of prescription digital therapeutics as an emerging treatment modality.”

Novartis is not alone. Other European pharma companies are signing contracts with digital therapeutics start-ups developing clinically-validated apps that improve patient outcomes directly, either through cognitive behavioural therapy, or by optimising how medicines are used.

GSK and Propeller Health are collaborating on an asthma inhaler that supports adherence and helps patients to use their device correctly; Roche and Voluntis are co-developing digital therapeutics that improve symptom management in cancer patients; AstraZeneca is studying the clinical value of mobile apps in ovarian cancer; while Sanofi is working separately with Voluntis and Innovation Health, an insurance company, on digital products that help diabetes patients to control their glucose levels.

European start-up companies are also in the picture. Paris-based Tilak is developing video games to diagnose and track chronic diseases; BioBeats of London has an evidence-backed stress-buster app targeting wellbeing in the workplace; and Finnish company Kaiku Health, an alumnus of the European Institute of Innovation & Technology’s Digital Accelerator, applies data science to cancer care and fertility treatment.

Several of the apps feature algorithms that use clinical care guidelines and patient information to make personalised care recommendations. As companies invest in generating the evidence needed to file for regulatory approval, payers, prescribers and regulators are working to get a handle on a fast-moving area.

New tech in an old system

The management consultancy McKinsey says the biggest barriers to widespread adoption of prescription digital therapeutics are public perceptions and economic incentives. For a start, it is hard for approved digital therapeutics to distance themselves from the unregulated mobile app free-for-all. “[They] are often not distinguished from the digital health and well-being market, which includes anything from sleep trackers to fitness apps,” according to a recent McKinsey report.

Then there is the issue of persuading healthcare systems to reimburse this new model prescription therapy. “The incentives for providers, payers, and pharmaceutical companies to adopt digital therapeutics are not well aligned,” the McKinsey report says.

Companies looking to crack the European market also face a regulatory vacuum. In the US, the FDA regulates drugs, devices, diagnostics - and now - digital therapeutics. FDA’s Digital Health Unit has set up a certification programme for developers of apps that are to be used in a clinical setting.

Meanwhile, in Europe, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has not set out a pathway for approving digital therapeutics and is stuck in the early stages of assessing how it should regulate an important new class of therapeutics at the same time as dealing with its attention-devouring relocation from London to Amsterdam.

The agency’s response to a request for information on its current position underlines how far it is lagging behind. “The EMA is not in charge of authorising medical devices and associated software,” it said. “However, [EMA] has been exposed to, and has a strong interest in discussions, concerning digital therapeutics.”

The job of figuring out the agency’s role in this area falls to its Innovation Task Force, EMA’s forum for early dialogues with companies working on innovative products, including digital therapeutics.

The EMA’s Scientific Advice Working Party also has a role in advising developers on digital products to be used in the context of drug development. But while this may apply to some algorithms used in data collection for clinical studies, it falls short of a route to regulatory approval for apps used in patient care.

The European Commission’s recent Communication on the digital transformation of health and care does not specifically mention digital therapeutics, however policymakers do see digital health as a way to improve patient outcomes.

Meanwhile, France has a small scheme for reimbursing new digital tools in healthcare. Although companies complain that the ‘forfait innovation’ is slow and complex, it may become a future model for embracing digital therapeutics.

Updated EU regulations

For now, existing digital therapeutics are covered by medical devices and diagnostics directives, both of which are being replaced by new EU regulations. These rules are being phased in over three- and five-year periods, respectively, beginning in May 2017.

Digital health start-ups are learning fast that to be taken seriously they may need to partner with established pharma or medtech companies with experience in securing reimbursement and market access.

Jörg Land, managing director of Sonormed, a company developing digital therapeutics for the audiology market, including a digital treatment for tinnitus, says the new medical devices regulation (MDR) will reclassify some digital technologies from the lowest risk class I to class II+ devices. That will increase the standard of evidence required to receive a CE mark, which is a prerequisite for use and reimbursement in Europe. Companies will need to invest heavily in generating clinical data if they want to market digital therapeutics after 2020.

“In general, the regulatory environment becomes more challenging after the MDR update,” said Land.

Sonormed has three products that are reimbursed in Germany and its experience of navigating the system has led it to rethink how it designs products. Rather than beginning with a technology, it now focuses on whether it will be covered by payers and welcomed by users.

“We now design our solutions backwards, beginning with the case for reimbursement and integrating feedback from patients, payers and physicians to create value for all of them,” Land said. “All our products need to solve an ENT [ear, nose and throat]-related health issue for the patient; [they also] need to be software-based, regulated and reimbursed.”

New reimbursement models

Edouard Gasser, CEO of Tilak, said products like its vision-monitoring OdySight app may be fast-tracked by the FDA. “When it comes to digital therapeutics I would say the US are a bit more advanced, based on their current initiatives for accelerating the process for digital apps, but it is still too early to say.”

On both sides of the Atlantic, the pace at which regulators are reviewing clinical apps lags the speed at which they are developed. “The process is slow compared to our production speed,” Gasser said.

US insurers have also begun to reimburse a small number of digital tools. “Since early 2018, providers can be reimbursed separately for time spent on the collection and interpretation of health data that is generated by a patient remotely and shared digitally with the provider,” said Gasser. “This is big news for digital therapeutics like ours, which will need support from payers and administrations to find the right reimbursement model.”

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.