With a struggle to attract foreign talent due to low salaries, and pandemic-driven economic crisis sparking cuts in national science budgets, researchers in EU13 countries are puzzling over how to tap new research programme to strengthen R&D systems

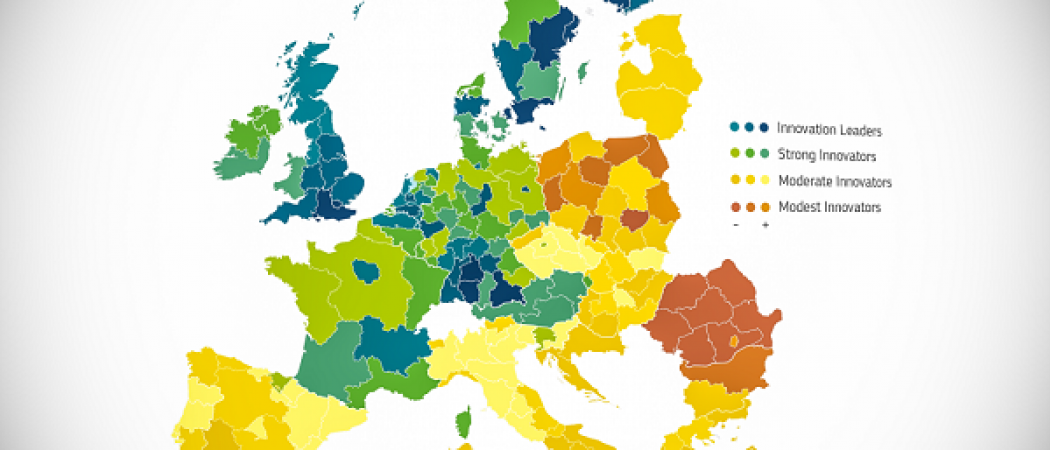

Data from the regional innovation scoreboard by the European Commission shows a significant R&D performance gap between EU member states

Over the next seven years the EU is to spend 3.3% of the €95.5 billion Horizon Europe budget on increasing participation by the EU13 newer member states, whilst at the same time, the European Commission is looking to encourage member states to coordinate R&D policies and boost national funding.

But with the full-on launch of Horizon Europe in limbo and the Commission’s pact for research and innovation still on the drawing board, research elites in EU13 countries are struggling to see how they can break the vicious circle of low pay and impoverished research systems, to capitalise on the EU’s new research programme.

Low pay means the struggle to attract talent from abroad will continue, while the economic crisis sparked by the pandemic is an excuse for cuts in national R&D programmes.

For Samo Ribarič, head of the Institute of Pathophysiology at the University of Ljubljana, recruiting expert researchers from abroad for a European Research Area Chair grant has been very difficult.

These grants, awarded under the outgoing Horizon 2020 research programme, were designed to help research institutions and universities in the so-called ‘widening countries’ with poorer R&D systems to bring outstanding academics from abroad, as the lynchpin of international research teams.

But in public research institutions in Slovenia and other EU13 countries, Horizon 2020 salaries are calculated from a base sum equivalent to the average pay for a civil servant, which is far below what leading scientists in the west of Europe earn.

“Salaries are not competitive if you wish to employ an expert from abroad,” Ribarič told Science|Business. “It would be helpful if you could get permission that this salary can be outside the scale for civil servants,” he said.

Horizon grant holders argue it is unfair to pay researchers on a fixed contract the same as a public servant with lifelong job security. “For such a call you advertise abroad for an expert with a professorship level qualification and you know the difference between the base salary and what [a researcher] could get in Germany for a comparable junior professor position is two or three times higher,” said Ribarič.

Jaroslav Koča, the new chair of the Czech Science Foundation, says salary gaps should be addressed on a case-by-case basis. “Comparing averages many times generates nonsense,” he said.

Koča was formerly the director of the Central European Institute of Technology (CEITEC), an institution involved in several widening projects aimed at boosting cooperation with research centres in richer European countries, in life sciences, advanced materials and nanotechnology.

As director of CEITEC, Koča hired some 20 new group leaders from abroad. Salary was an issue in 10% of cases. For the rest, “it was the second or third question,” he said.

Some Czech institutions can offer salaries that are competitive with other countries in Europe, with the exception of the UK and Scandinavia maybe, where the cost of living is much higher. “Yes, salaries are important, but averages would not tell you anything,” said Koča.

Reviving the European Research Area

The pact for research and innovation is part of the Commission’s ambition to revive the European Research Area (ERA) plan to create a single market for research in the EU and encourage “brain circulation” between member states.

As things stand, a number of EU programmes don’t support that goal. While Marie Skłodowska Curie (MSCA) fellowships for PhD students offer competitive salaries, other Horizon grants are still tied to base salaries in national institutions. “If they could do this for MSCA, they could do it for other categories,” said Ribarič.

Slovenia takes on the presidency of the EU Council in July, when one focus will be on helping young researchers build successful careers in their home countries. It will push for academic exchange schemes to be improved so that institutes in poorer member states can attract talent from abroad with competitive salaries.

During the 2008 -2009 financial crisis governments in central, eastern and southern Europe bowed to continent-wide austerity measures and slashed R&D budgets. Some countries have yet to reach funding levels from before the crisis.

Koča believes these countries will not repeat the same mistake in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. “The two crises are completely different,” he said. While one was a global financial crisis, handling the pandemic is highly reliant on science. Governments will continue to make investments in R&D to deal with the health emergency. “Politicians wouldn’t be too clever to say we cut the budget for science,” said Koča.

Slovenia’s national research agency faced cuts after the 2008 crisis and still has a limited budget, all of which is spent on competitive calls.

“I still feel that more money should be allocated to research and innovation,” said Ribarič, noting a bigger budget would help researchers and innovators develop new products and services, while a banking reform would enable banks to provide loans for funding start-ups and small companies that are trying to commercialise research. “If those start-ups don’t get seed money, they may just move to the US, or not succeed,” Ribarič said.

The revamped ERA strategy encourages member states to put more money into research and innovation. However, Koča argues national R&D budgets should also be linked to the quality of science, to avoid wasting resources on projects there isn’t the capacity to deliver. “If you overpay scientists, you probably waste money, but if you underpay scientists, you waste human resources,” he said.

Another problem for the Czech Republic is that it disperses R&D money through about 15 different institutions, including the ministries of health, education and agriculture. “Maybe a single provider is not a good idea,” but 15 is certainly too many, Koča said.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.