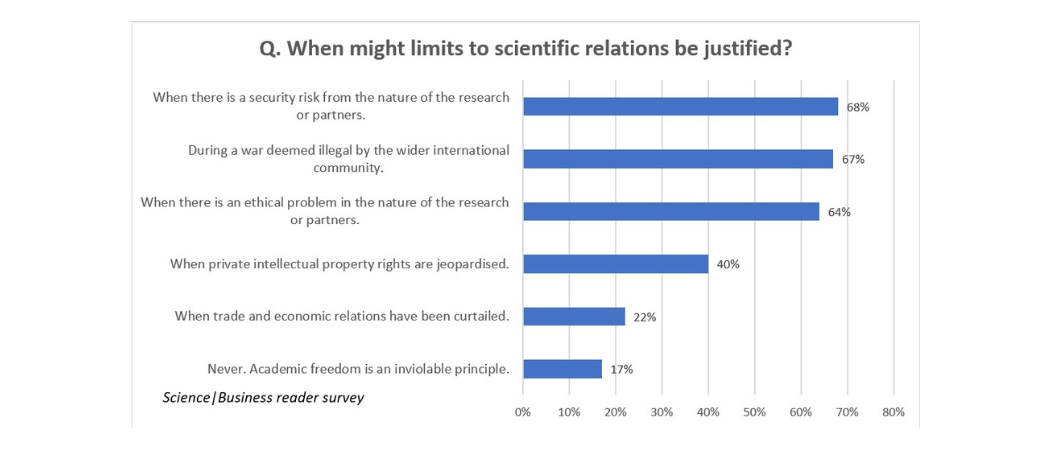

An opinion sample finds most agree that scientific ties should be curtailed with countries that start wars or pose security or ethical problems – but trade and IP disputes are a different matter

Results of Science|Business online reader survey, 28 June to 25 October, 419 respondents

As geopolitical tensions mount, how should the scientific world respond? The answer, say many Science|Business readers: do get tough with countries that pose security and ethical risks, but don’t use science as a weapon in economic or trade disputes.

In an online sampling of opinion, about two-thirds of the 419 Science|Business readers responding agreed that limits on scientific cooperation “may be warranted” with countries engaged in an illegal war, or whose work could pose a security risk or ethical problems.

But fewer than half of the survey respondents believe economic conflicts, such as trade or intellectual property disputes, would justify limits to scientific cooperation. And 17% say scientific relations should never be curtailed, because “academic freedom is an inviolable principle.”

The split in opinion reflects the growing complexity, and confusion in the scientific community, over how to operate in a world that suddenly looks a lot less open to international cooperation than it did only a few years ago. Besides the war in Ukraine, which has prompted many western governments and institutions to halt formal collaboration with Russian counterparts, there is growing fear in the West of economic or even military conflict with China, Iran and North Korea.

“Science is not immune from politics - we all need to understand this,” wrote one Belgian reader of Science|Business, commenting anonymously.

The survey ran on the Science|Business web site from 28 June to 25 October, as a way of sampling reader opinion rather than seeking statistically significant results. Still, most readers drew a sharp line between security and economic disputes.

In the event of war…

Of all 419 respondents, 68% agreed that curtailing scientific relations may be warranted “when there is a security risk from the nature of the research or partners.” And 67% took the same line about “a war deemed illegal by the international community.” That view, though dealing with hypothetical future conflicts, also tracks the results of another question in the survey, specifically asking about research collaboration with Russia as the war in Ukraine drags on.

Likewise, 64% of readers agreed that curtailing scientific ties may be right “when there is an ethical problem in the nature of the research or partners.” That view fits in with long-established norms in the scientific community, of staying away from research collaborations that seem unethical – such as facial recognition R&D that could be used to discriminate against minority groups, or medical research in which test subjects haven’t had the opportunity to give informed consent.

The 245 respondents who identified themselves as professional researchers took an even stronger line than the general readership, with 71% saying sanctions are justified in war, 70% for security risks, and 65% for ethical problems.

Wrote one Hungarian researcher, “We, the producers of know-how and knowledge, are also responsible for how our results are or might be used, even by others.”

IP and trade are different

But economic disputes are, in most minds, a different matter entirely. In all, just 22% of readers agreed scientific relations could be limited “when trade and economic relations have been curtailed.” And 40% see limits “when private intellectual property rights are jeopardised.” The issue is far from hypothetical, as IP theft and unfair competition was cited often by the Trump administration in its efforts to crimp US-Chinese scientific collaboration, and has lately risen on science policy agendas in Europe, as well.

But governments clearly don’t have the backing of the scientific community for this. As an Italian researcher wrote, “security and competitiveness matters should not become a way to move towards 'scientific protectionism'.”

Many also view it as impractical. Wrote a Swedish researcher, “It would be difficult to apply the same sanctions to China as we have done on Ukraine.”

Then there are the ‘fundis’, or fundamentalists, on both sides of the dispute. About 15% of all respondents ticked all the survey boxes justifying scientific sanctions for both security and economic cause. And at the other end of the spectrum, 17% said political interference with academic freedom is never justifiable. The results were similar for those respondents who identified themselves as researchers, with 18% backing a hardline sanctions policy, and 17% defending academic freedom under any circumstances.

For many readers, however, the whole issue is a mess. You can almost hear a frustrated sigh in the short comment of one German researcher, “It’s really difficult…”

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.