Some people see the anglerfish, a toothy, glowing creature from the deep sea, as the stuff of nightmares. In the film Saving Nemo, it plays the role of a hideous predator, luring innocent fish to their doom with its eerie light.

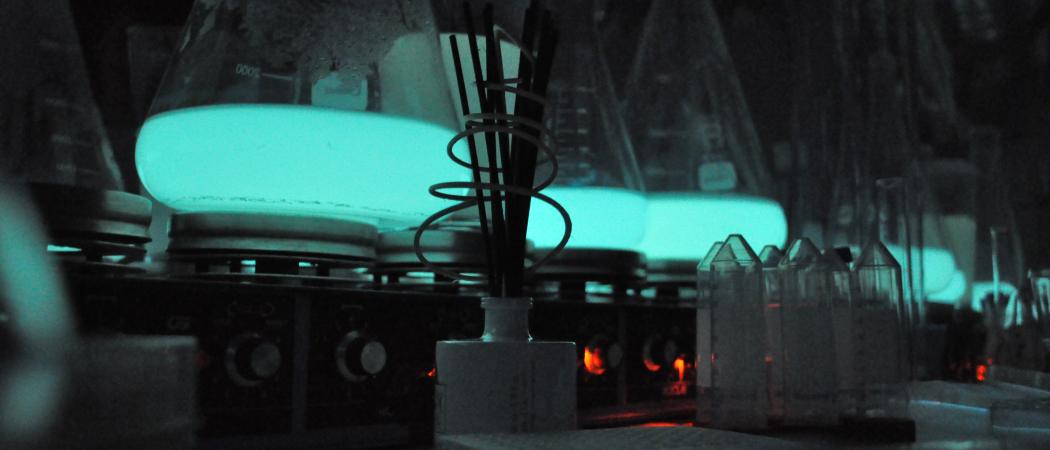

To Sandra Rey, the anglerfish is an inspiration. She won a school science and design contest with a project on bioluminescence and now runs a successful start-up named Glowee with €2.5 million in capital and 18 employees. Glowee has used bioluminescent bacteria to create a soft, green light for events for the likes of LVMH, Adidas and Vinci Energies and is now exploring applications in architecture, design and sports.

Glowee is one of hundreds of start-ups helped by the European Institute of Innovation and Technology, which is currently celebrating its 10th year of operations. The EIT, launched by the European Union, manages public-private networks to stimulate innovation. It has grown to more than 1,000 partners today and is present in every EU country.

For Rey, the EIT’s energy-sector network, EIT InnoEnergy, saw promise in her project after it got featured in French media. At the time, she had just finished the Strate School of Design near Paris and had little experience in fundraising, research and development, management, business regulations or any of the other challenges ahead.

“EIT helped from the very beginning,” Rey says. Its European start-up incubator and accelerator network helped her secure venture capital, provided mentors and invested some seed capital of its own to help her get started and grow.

Oana Penu, a project officer at EIT InnoEnergy, says Glowee ticked all the boxes to qualify for attention: It was innovative, related to sustainable energy, was still early-stage, had real market potential and above all had a team that showed promise (An InnoEnergy marketing brochure says “We do not believe in the ‘superman or superwoman’ but in the “super team.”)

In 2016, the EIT helped Sandra launch a crowd-funding campaign, which raised €700,000 from 600-some individual investors and others in just 9 days. The same year, Glowee got some bragging rights after MIT’s Technology Review magazine named Sandra one of the top 10 young French inventors to watch.

At the same time, Rey was beginning to wade into the potential minefield of business regulations regarding the sale of products using living organisms. Glowee’s bacteria are genetically modified micro-organisms, so they fall under the broad umbrella of biotechnology. “The commercial use of living modified micro-organisms that stay contained is not regulated,” Rey says, describing the situation as a “regulatory void.”

Via its office in Brussels, InnoEnergy set up meetings with people who know the EU regulations inside-out. They helped Glowee navigate its way to a product strategy that passed muster.

The market, meanwhile, was all too eager to start seeing products. LVMH and other design and luxury brands were intrigued by the prospect of an organic energy source and the “hypnotic light” that it produces and were early customers of the first lighting products.

While Glowee is working on developing a continuous lighting system, for now the products that they display are still limited to short-term uses; they stop working without a steady food supply and room to grow. Still, there is plenty of potential for innovative lighting in the short-term for ephemeral events and on-demand lighting (think glow-strips).

Rey is looking at the big picture. For her Glowee offers a potential solution to light pollution in cities. It is a 100 per cent natural, organic lighting source that could eventually replace LEDs and their rare metals. And she is enthusiastic about the creativity that can be unleashed by a light source applied to whole surfaces as opposed to coming from single points in space.

EIT InnoEnergy still shares Sandra’s enthusiasm for the technology. Each time she has raised new capital, it has raised its own stake in order to avoid diluting its share.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.