Romanian government scrambles to help mend relations between EU-funded laser research facility in Bucharest and counterparts in Hungary and the Czech Republic

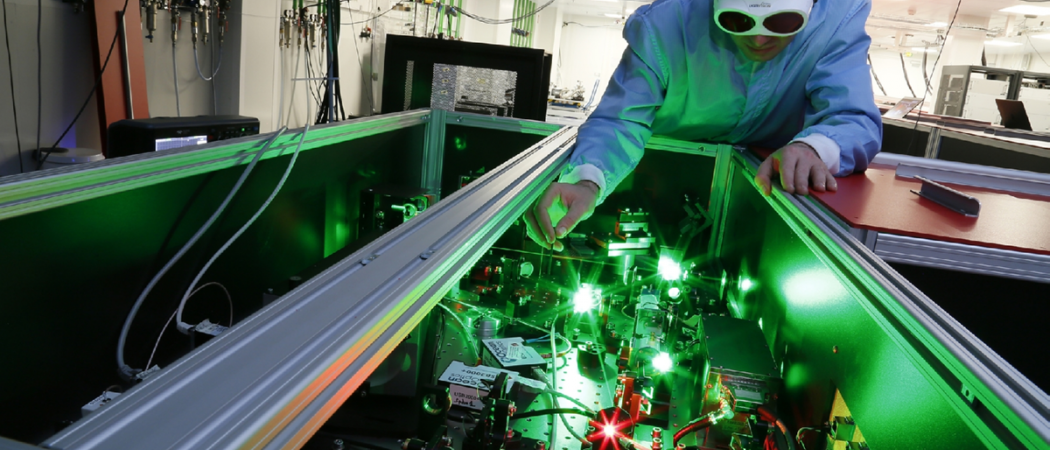

Researcher tests laser at ELI-NP. Photo: Thales.

The rising star among the large research laboratories in eastern Europe is flickering.

When EU ministers first approved the project in 2009, the Extreme Light Infrastructure (ELI) was meant to be the world’s first international laser research facility centred around three founding sites in the Czech Republic, Hungary and Romania. Its basic mission was, for the first time, to use EU structural funds to co-finance the building of three laser research sites, which would then be combined with member contributions to a European Research Infrastructure Consortium (ERIC) to finance long-term operations.

The three facilities were established to welcome researchers from across the world in an attempt to spur discoveries and innovations in nuclear materials and radioactive waste management; industrial tomography and gamma radiography; pharmaceutical radioisotopes; medical imaging; radiation and proton cancer therapy.

By now, the three facilities were expected to be moving together beyond the construction phase and establish the ERIC to deliver on its scientific mission. But years of conflicts around the Bucharest-based facility ELI-Nuclear Physics (ELI-NP) have marred relations in the consortium and prompted the other partners to move forward without Romania.

In May, the Czech Republic and Hungary, together with Italy and Lithuania, formally applied to the European Commission to establish ELI-ERIC without the participation of Romania. The UK will also join as a founding observer.

In the application sent to the commission, the countries had to demonstrate the political support needed to finance the facilities in the future, beyond the initial building costs which have been mostly covered by the EU. If the application is accepted by the commission, the Czech and Hungarian facilities will operate together as the world’s most advanced laser laboratories under the umbrella of the ERIC.

“This application is a significant milestone after a decade of planning and construction,” said Allen Weeks, director general of the ELI delivery consortium. “The newly formed ELI ERIC will organise the joint scientific user programme and begin to coordinate the technical operation.”

Following the announcement, the management of ELI-NP has accused the other partners in the ELI delivery consortium of trying to “isolate” the Bucharest facility from the European scientific community. “Claiming that ELI-ERIC without ELI-NP has the same qualities, performances and potential is groundless and does not correspond to the scientific and technical reality,” the management said in an open letter in May, calling for the application to be rejected and resubmitted with the participation of Romania.

“We expect the commission to reject the application because it is contrary to its decisions [on ELI] so far,” Nicolae Zamfir, the director of ELI-NP told Science|Business.

The gamma quarrel

For many, the decision of the delivery consortium to move on without Romania did not come as a big surprise. In 2018, ELI-NP terminated a €67 million contract with the European consortium EuroGammaS, saying it had failed to deliver a gamma beam, after the consortium complained the building in Bucharest was not suitable for the equipment.

Following a new tender process, in 2019 ELI-NP decided to contract California-based Lyncean Technologies to build the Variable Energy Gamma-ray (VEGA) system for €42 million, with delivery due in by 2023.

“The steps that were taken in late 2018 were unexpected for the partners in the ELI delivery consortium,” said Roman Hvězda, deputy director at ELI Beamlines in the Czech Republic.

Members of EuroGammaS are also part of the ELI delivery consortium, which is why the row over the gamma contract in Bucharest was a sore point for people involved in putting together the ERIC application. Members of the delivery consortium were representing institutions which had already become party to a litigation over the gamma beam and the legal conflict created the perception that collaborating institutions were in fact fighting each other. “It was not the most favourable environment,” said Hvězda.

The delivery consortium had two options: either delay establishing the ERIC until all issues were solved, which could take years, or to try to reduce the scope of the infrastructure, establish the ERIC and remain open for ELI-NP and Romania to join at a later stage. Hvězda said the decision to establish the ERIC without Romania is not intended to comment on ELI-NP’s scientific and technological progress. “It’s not a conspiracy to exclude them,” he said.

Since the litigation is still ongoing, stakeholders were “naturally motivated to establish the ERIC and open the opportunity that other countries can join,” said Hvězda.

As cooperation talks moved into a legal dispute, there was plenty of blame to be shared around. But Zamfir argues that members in the consortium should have kept friendly scientific collaboration separate from the legal case over a “commercial contract.”

Political commitment

Zamfir’s main complaint is that he was not informed in due time about decision of the consortium to move forward without Romania. “We were taken by surprise,” he said.

On the other side, Weeks told Science|Business that the management of ELI-NP was told in a meeting of ELI scientific advisory committee in November 2019 that Hungary and the Czech Republic would go ahead. “[ELI-NP] were absolutely consulted in advance,” Weeks said. “At the lab level they knew, but we haven’t heard from anyone in the government.”

A lack of timely response from the Romanian government seems plausible. Romanian researchers have previously complained that frequent changes in leadership at the research ministry are to blame for the chaos in national research funding. In 2018, the socialist government appointed Nicolae Hurduc as its fourth pick for research minister since 2016. In 2019, a new conservative government was appointed and decided to merge the research ministry in a broader education portfolio.

According to Zamfir, the Romanian government is now aware that it will have to make up for the “lack of a consistent dialogue over the past years.”

In an interview for Romanian media, state secretary for research Dragoș Ciuparu said the conflict made it obvious that the “diplomatic component was missing from the mix of competences needed to implement a project of such scope.”

Ciuparu said the government was surprised by the move to establish the ERIC without Romania and has pleaded for Czech and Hungarian partners to reconsider their decision and come back to the negotiating table.

The delivery consortium says Romania can still join the ERIC, most likely in the autumn or in early 2021, but not as a founding member under the current application. “I believe that train has left the station,” said Weeks. “It will be easier to discuss Romania’s membership within ERIC.”

Weeks said the consortium wants to avoid losing another year until the quarrel is sorted and the “scientific community gets sour on the whole thing.”

“Waiting and not establishing the ERIC would probably be less attractive than actually moving ahead now,” said Weeks.

Ciuparu did not answer interview requests by Science|Business.

Another bone to pick

According to sources familiar with the talks inside the delivery consortium, there were two conflicting views about how ELI-ERIC should function and how much autonomy each laser site should have. The Czech Republic and Hungary envisioned an integrated international facility, where research groups could apply for access and be evaluated under common standards.

But Romania wanted more autonomy and the ability to use its funding surplus to support national projects and help boost local researchers with little chances of winning access bids against colleagues in countries with better and more adequately-funded research systems.

However, this proposal did not go down well during governance debates where parties were discussing the details of the ERIC. Each member country of the ERIC would pay a contribution that would then be distributed to each site, depending on needs and ongoing projects, but they did not want the money for operational costs to be used indirectly on projects outside the international competition.

Despite the differences, the three ELI sites are moving forward with a joint Horizon 2020 project which is set to officially kick-off common research activities in all three facilities. ELI-NP has a €4 million stake in the project.

It is a middle ground for all parties to remain involved in a joint project at a scientific and technical level, while governments sort out the political differences. “All partners have said this is the very best mechanism to stay engaged,” said Weeks.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.