The experimental reactor won’t start operating until 2034, nine years later than the last estimate

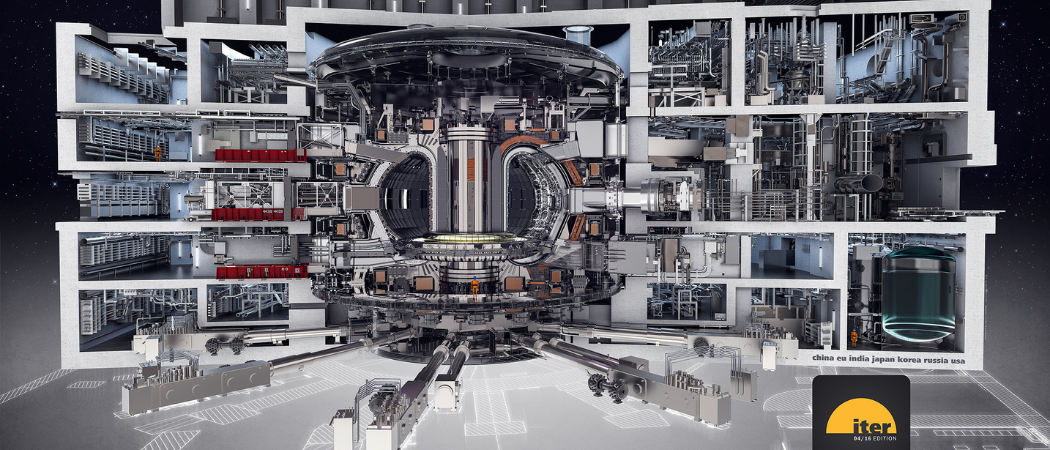

A drawing of the ITER tokamak and integrated plant systems. Photo credits: Oak Ridge National Laboratory / Flickr / ITER Organisation

The International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) has confirmed yet more lengthy delays and around €5 billion in extra costs, in the latest setback to the scientific mega-project.

Designed to demonstrate the feasibility of fusion power at a site in the south of France, ITER been hit by hold-ups due to the pandemic, component faults, and a pause on construction demanded by the French nuclear regulator, in part due to concerns about on-site radiation.

Explaining the delays in a press conference yesterday, director general Pietro Barabaschi also said that planning had been “too optimistic”.

“Some things could have been foreseen a little bit better, in terms of difficulties and risks that may have incurred in the manufacturing and assembly,” he said.

The result is that the final stage of the ITER plan, a fusion reaction involving deuterium-tritium fuel, is delayed until 2039, rather than 2035, as under previous plans made in 2016.

What’s more, ITER has dropped plans to turn on the reactor next year to create a plasma for the first time, and will instead only start research operations in 2034.

Barabaschi played down the significance of this now-scrapped “first plasma” experiment, saying it was only ever going to be of minimal scientific value. “The first plasma was really rather symbolic,” he said.

Instead, when the reactor fires up in 2034, it should be more complete, allowing for more fulsome experiments, Barabaschi said. The schedule has been rejigged to use newly available components to build a more finished machine, before it gets fired up.

Still, there was no sugarcoating that this is another delay for ITER – and an expensive one.

Barabaschi said the new plan – dubbed a “baseline” – would cost an extra €5 billion.

“We are reorganising massively the project within in order to work with more efficiency,” he said.

ITER’s members - China, the EU, India, Japan, South Korea, Russia and the US – will now have to decide whether to continue investing in the project, despite delays and new costs.

Asked about the reaction of members when they met to discuss the new plan, Barabaschi said that “nobody fell from the chair” in shock.

There was “no cheering” but “my personal impression is that there is still very strong support from the members on this project,” he said.

ITER is only planned as an experimental reactor, and is not set to produce electricity. Even its planned successor Demo – which is still at the drawing board phase – will not produce power at commercial rates.

Advocates for fusion have long argued that it could help with climate change, because it has the potential to produce huge quantities of zero carbon energy with almost zero waste.

But given the further delays to ITER’s schedule, Barabaschi played down the idea that fusion might provide a solution to climate change, except in the long term.

“I trust there will be a point in time where it will play an important role,” he said. “But I am not going to be a person that will tell you fusion will solve all problems and will not solve them at the time that they should be solved, because the time to be solved it's yesterday.”

“Humanity should focus on using the technologies that we have now in hand,” he said, including nuclear fission and renewables.

Over the past decade, dozens of private fusion firms have emerged, promising much faster results than ITER, some claiming they will achieve commercially priced power from fusion by 2040.

But Barabaschi is unconvinced by these timelines. “I am very sceptical,” he said.

ITER would do its best to help them, he said. “But from my standpoint, even if we would have, today, thermonuclear fusion proven, I don't believe we would be in a position to have it commercially deployed by 2040,” he said, as there were so many other technological hurdles to overcome before it is commercially viable.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.