Tensions with China have made scientific cooperation with the West more fraught. But in Latin America, Africa and the Middle East, collaboration is largely unaffected by geopolitics

Photo credits: chughes / BigStock

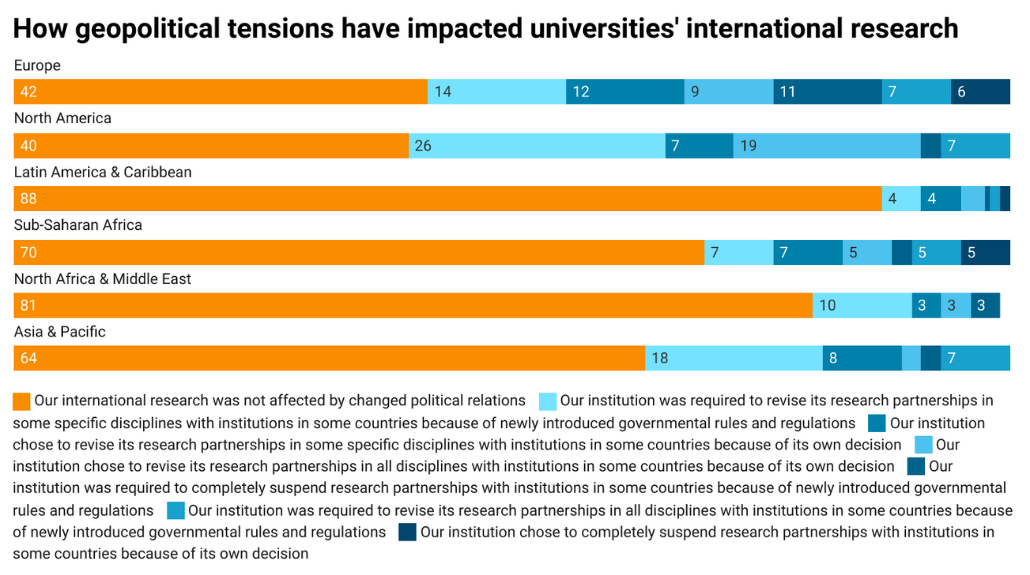

A survey of more than 700 universities worldwide has found that geopolitical tensions have cut global research links in Europe and North America far more dramatically than in other areas of the world.

More than half of universities in Europe or North America said they have restricted partnerships either because of new government rules, or on their own initiative.

There has been a flood of new security measures introduced in G7 countries, largely due to fears of sensitive knowledge leaking to a technologically and militarily ascendent China.

Most recently, the European Commission told universities to tighten further their research security, while in the US, the National Science Foundation is planning a new security guidance centre.

But the vast majority of universities in Latin America and the Caribbean, sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa and the Middle East said their partnerships have not been impacted by geopolitical tensions.

The survey results from more than 100 countries, part of a series of reports by the International Association of Universities conducted roughly every five years, suggest that the issue of knowledge security is not yet a global phenomenon, said Hans de Wit, a senior fellow at the association.

“The issues of geopolitical tension and knowledge security in particular is much more an issue in Europe and North America as well as Australia […] and in their relations with Asia, in particular China,” he said.

“While some countries are playing out a Cold War logic, the world as a whole is not following this game plan,” said Simon Marginson, a professor of higher education at Oxford University.

The results show that universities in North America in particular have been taking their own measures, rather than being forced to by governments. Almost one in five said they had changed their partnerships “in all disciplines” with some countries on their own initiative.

Meanwhile in Europe, 17% of universities said they had completely suspended relations with institutions in some countries, either because of new government regulations, or because of their own decision.

The results don’t clarify which country, but this could refer to the wave of European countries that cut institutional research ties with Russia following the invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

North American universities were more likely to have revised partnerships, rather than entirely cutting them off.

German universities appear to have been particularly proactive. Of 37 that responded to the survey, 31 said they had revised or suspended partnerships in some way. In the case of 18 institutions, this was their own decision, rather than government mandate.

Perhaps unsurprisingly given the invasion by Russia, all but one of the Ukrainian universities surveyed chose, or was required, to restrict its international partnerships.

A power issue

One obvious reason why much of the world has not stepped up its research security is that many countries have not chosen sides in the rivalry between a US-led West and China.

“In Indonesia, Malaysia, large parts of Africa, Latin America and Central Asia there is no desire to take sides in a China/US imbroglio,” Marginson said. “The hostility towards China that is driving decoupling in science and technology is very much a Western and primarily American led phenomenon.”

“The US State Department has had considerable success in influencing policy in the rest of the Anglophone world and Western Europe – primarily, in those nations that are white, closest historically to American power, and that share with the US fears about the ‘decline of the West’.”

Another reason why research security concerns have swept North America and Europe is that these regions arguably have more of the advanced technologies worth protecting.

“Knowledge security is a power issue and that power lies predominantly in the global north and China,” said de Wit. Meanwhile, parts of Asia, Africa and Latin America are still focused on the short-term benefits of partnerships with China, such as investment and scholarships, rather than the long term question of knowledge security, he added.

Despite surveying 722 universities, the report only includes a handful of responses from East Asia, making it impossible to judge whether Chinese, Japanese and South Korean universities have taken similar measures to their European and North American counterparts.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.