The BRICS research framework programme, running since 2016, uses strikingly similar language to those run by the EU. But the organisers insist it is not modelled on the EU programmes. Science|Business takes a look

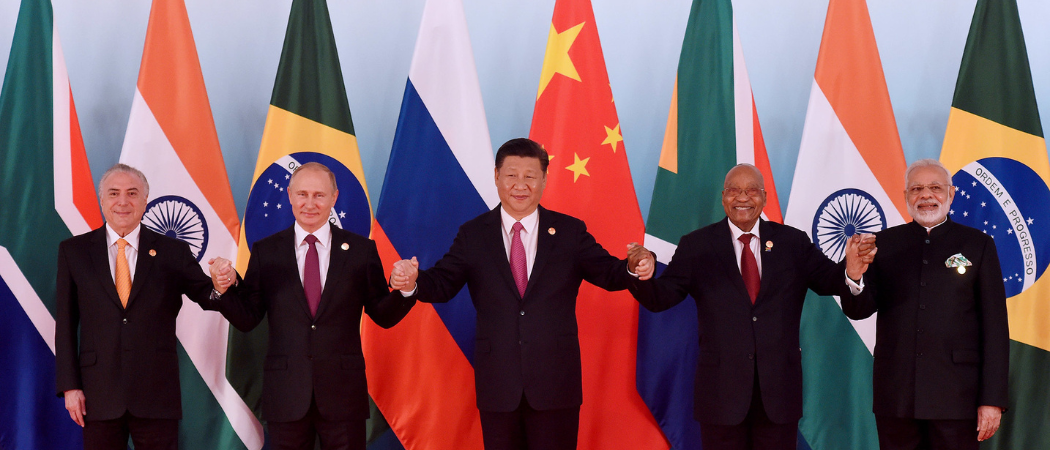

9th BRICS Summit, Xiamen International Conference Centre in China, September 2017. Photo credit: South African Government / Flickr

Think of the BRICS, and you might imagine, fairly or not, the world’s strongmen – plus a few democratically elected leaders from the Global South - clinking glasses and plotting how to challenge western hegemony.

The grouping of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa was invented back in 2001 by Goldman Sachs as an investment class of rapidly growing economies (minus South Africa, which joined later).

Despite starting life in a report by a US investment bank, the BRICS have evolved into a loose geopolitical bloc that is ambivalent or hostile towards a US-led world, with leaders meeting once a year.

Since it was formally founded in 2009, there have been a few achievements, like the creation of a multilateral lender, the New Development Bank, but critics have pointed to a lack of concrete actions.

But what’s less known about the grouping is that since 2016, it has had its very own joint research and innovation scheme, called the “BRICS STI Framework Programme”.

It uses strikingly similar language to the EU’s own research and innovation framework programmes – it even has “national contact points” – although the organisers insist it is not modelled on the EU programmes.

The BRICS framework programme launched pilot calls back in 2016, after member countries agreed the previous year to step up science, technology and innovation cooperation.

Compared to Horizon Europe, the sums involved appear to be pretty small. The pilot call was worth around $80 million, with eight national funding agencies and ministries chipping in $10 million each. Projects should last three years, according to the latest call.

Since then, there have been five further rounds of funding, although the value of these rounds hasn’t been made public, and none of the agencies involved would disclose them to Science|Business.

New members

But the budget will grow as new countries join the BRICS grouping, said Yaroslav Sorokotyaga, an official at the Russian Centre for Science Information (formerly the Russian Foundation for Basic Research), which is currently acting as the secretariat for the BRICS framework programme.

“The budgets vary from call to call, but in general the cumulative call budgets are expected to grow of course, at least due to the fact that BRICS have doubled in number of member countries,” said Sorokotyaga.

At the beginning of this year, the BRICS grouping gained five new members: Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Egypt (which was recently invited by Commission president Ursula von der Leyen to start talks on Horizon Europe association).

Some of these new countries have started the process of joining the framework programme and are “eager” to start participating “as soon as possible,” Sorokotyaga said. New ‘flagship projects’ are also in the works but there’s little information yet on what they will actually entail.

In 2022, no calls were issued, although there’s no evidence this was anything to do with the Russian invasion of Ukraine. None were issued in 2018 as well. Sorokotyaga said that 2022 was skipped because the programme was still implementing the call made in 2021.

Dual use technology

One persistent criticism of the BRICS grouping is that it is too geopolitically disunified to ever act as a powerful common bloc.

Most pertinently, relations between China and India, the two most populous and economically powerful BRICS countries, are in a deep freeze after deadly unarmed skirmishes between their soldiers in contested parts of the Himalayas in 2020 and 2021.

It might therefore come as a surprise to learn that – at least until 2022 – the BRICS framework programme has included at least some calls on sensitive and even dual use technologies.

Calls in 2016, 2017, 2019 and 2021 included calls on high performance computing and nanotechnology, for example. The 2019 call ended up funding projects into nanomaterials for “for advanced electronic devices” and “quantum satellite and fibre communication”.

Meanwhile, in 2016 and 2019 there were both two funded projects in geospatial technology.

In 2019, the BRICS framework programme introduced a new category of call for aeronautics projects. That year, a Russia-Chinese-Brazilian project to cope with the noise coming from aircraft engines was funded.

Aircraft research

Two years later, the 2021 call asked for proposals on “modern aviation aircraft research” including “short take-off and landing transport aircraft” as well as “composite damage behaviour research”, although none appear to have been funded.

Then, after no calls were made in 2022, the scope of the programme in 2023 was dramatically narrowed, just to focus on climate change.

To be fair, this is not as abrupt a shift as it sounds. Despite a few pockets of sensitive tech, most of the calls and funded projects have always had strong green hue, sounding not that dissimilar to what gets funded by Horizon Europe.

There have consistently been calls on areas like renewable energy, natural disaster prevention, and water treatment. The 2021 call stipulates that any high-performance computing research should serve environmental goals, for example.

And 2023 wasn’t the only year in which the programme suddenly switched to one issue. The 2020 call was entirely pandemic-related.

“Some calls are more narrow[ly] focused,” explained Sorokotyaga. Asked whether any topics are too sensitive for cooperation, he says that the “adoption of each call topics is a joint decision of the group”.

Perfectly balanced

One striking feature of the BRICS framework programme is how evenly balanced the successful calls are between all five countries.In the 2021 call, for example, researchers from South Africa (population 59 million) were part of 20 successful bids. Academics from China (population 1.4 billion) only did marginally better, winning 26 bids. The other three countries came somewhere in between.

The EU’s programmes do have Widening measures to make sure scientifically weaker countries in the east and south of the continent don’t get too left behind, but the biggest winners are inevitably countries like Germany, France and the UK which have the most cutting-edge research and biggest budgets.

The BRICS’ more egalitarian approach appears to be due to funding rules: each project must include scientists from at least three of the five BRICS countries, and one of the evaluation criteria is “balanced cooperation”.

Two track system

Unlike the EU’s programmes, there’s no single application process. Cross-country teams need to both submit a joint proposal to the BRICS secretariat, and also apply individually to their own national funders for money to cover their own chunk of participation.

This two-track system inevitably causes hiccups. Jianyu Yuan, a materials science and engineering professor at Soochow University in China, applied for funding for a solar cell innovation project along with collaborators from Russia, Brazil and India. This joint application was approved, but his Indian partners failed to win national funding.

“Each funding agency will send out these detailed proposals for peer review and all applications must be approved before they can finally access funds,” he said. Fortunately, Yuan’s project still had enough other BRICS partners who were successful with their domestic agencies to succeed.

But this multi-stage, multi-agency application is why BRICS funding calls come at irregular times, thinks Yuan.

Along with other applicants, Yuan complains about the scheme’s low success rates, which stand in China at about 10%. The 2021 call received 333 applications, of which just 33 were successful.

“It’s quite competitive due to the large number of teams applying,” said Tricia Naicker, an associate professor at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, and part of a winning consortium on a project tackling antibiotic resistance. “I was successful after my fifth attempt!”

However, one of Naicker’s collaborators, Hua-Li Qin, a chemistry professor at Wuhan University of Technology, said he has still not received his funding, despite his Indian and South African collaborators having done so. He’s unclear what’s caused the delay.

These problems aside, Yuan, and most other BRICS scientists who spoke to Science|Business, are happy with the programme. Last year, Yuan visited Moscow to meet his Russian collaborators, with whom he has published a joint paper. He’s also received his funding, worth around €250,000.

“The good thing is that we see steady approved funds in the past decade, [about] 30 every round,” he said in an email. “In the future, I believe the organisation will be more efficient.”

Editor's note: this article has been updated to clarify that no calls took place in 2018, and to include the new name of the Russian Foundation for Basic Research

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.