There’s concern the military technology alliance could exclude the EU from cutting-edge science. AUKUS is now looking to involve Canada, New Zealand and South Korea, potentially forming an alternative joint defence R&D initiative to the EU’s own framework programmes

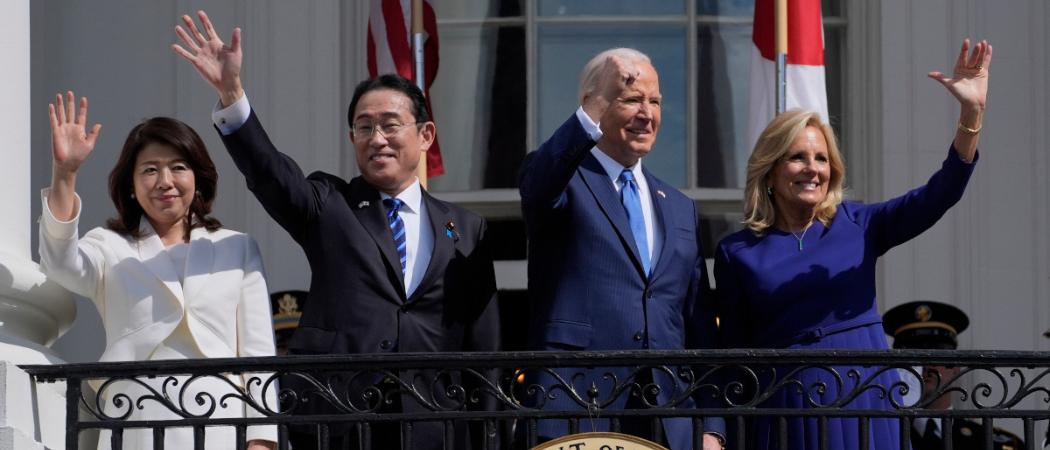

U.S. president Joe Biden, his wife Jill Biden (right), Japanese prime minister Fumio Kishida and his wife Yuko Kishida (left) at the White House, April 10, 2024. Photo credits: U.S. Embassy and Consulates in Japan

The AUKUS defence partnership between the US, UK and Australia has said it is looking to cooperate with Japan on military technology projects, but for now there’s no sign of EU countries being allowed to join, even as Brussels tries to ramp up defence R&D.

Announced in 2021 to counter China in the Indo-Pacific, AUKUS caused a diplomatic row with Paris over its centrepiece deal to supply Australia with nuclear-powered submarines, cancelling a prior French contract.

But beyond the submarine deal, AUKUS is also emerging as a military technology partnership, promising joint work on areas ranging from cybersecurity to quantum positioning and navigation. Last month the first tenders for research proposals under this so-called pillar II of the AUKUS pact were released.

All three countries are lowering export control barriers to allow relatively seamless joint military R&D and technology exchange, but there’s some concern this could leave EU countries at a relative disadvantage if they want to work with AUKUS countries.

Last year Australian universities raised the alarm that these changes could make work with non-AUKUS countries much more difficult, although concessions were made by the government to avoid this.

“We're staying really vigilant about the development [of AUKUS]”, said Thierry Botter, executive director of the European Quantum Industry Consortium.

“What's really important is offering quantum businesses from like-minded countries the ability to work together,” he said. “AUKUS is certainly focusing on three of these nations. But we know that there are companies from a much larger set of like-minded nations that are all pushing the growth of quantum technologies.”

Earlier this week, AUKUS defence ministers put out a joint statement saying that they were “considering cooperation with Japan on AUKUS Pillar II advanced capability projects”, in advance of a visit by Japanese prime minister Fumio Kishida to Washington DC.

The pact is also mulling over inviting other countries to cooperate too. “Japan is one of several additional partners that the AUKUS partners are closely considering partnering with,” according to a White House press briefing on 10 April.

In February, UK defence secretary Grant Shapps said that Canada and New Zealand were in the frame to join a programme of pillar II projects. South Korea is also under consideration, it was reported this week in the Korean media.

These are the very same countries that have agreed to associate to Horizon Europe, the EU’s research and innovation programme. Brussels is also in talks with Japan to join.

With moves afoot in Brussels to make Horizon Europe’s successor in 2028 permit military-related research, an expanded AUKUS could form an alternative, albeit far narrower, forum for joint defence R&D among the world’s democracies.

EU not in the queue

There’s no indication yet that any EU countries are in the queue to join AUKUS.

To be fair, most EU countries have few troops or ships in the Indo-Pacific, where AUKUS is focused in order to counter China.

The exception however is France, which has more than 7,000 troops in the region, defending French island territories to the west of Australia and dotted around Madagascar.

Meanwhile, France overtook Russia to become the world’s second biggest arms exporter in the period 2019-2023, according to data released last month by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

It accounted for 11% of global exports, boosted by strong sales of the Rafale combat aircraft. The US remained the world’s biggest seller, making up 42% of exports.

Some voices in AUKUS would welcome more EU engagement. “Research and development often builds on a much broader base than just Australia, US and the UK,” said Len Sciacca, enterprise professor for defence technologies at the University of Melbourne.

“Including Japan, Korea and even European countries makes for a greatly improved capability development. For universities, limiting defence research to be exclusively AUKUS will slow down research outcomes,” he said.

But given the huge diplomatic row AUKUS caused when launched in 2021, it could be a bitter diplomatic pill for Paris to swallow to come on board as a second-tier partner in joint AUKUS projects.

French and EU defence organisations were tight lipped about such a sensitive matter, although one senior figure in French defence R&D said they privately hoped the EU would be involved in AUKUS.

ASD, an umbrella body for the European aerospace, security and defence industry, declined to comment, as did Gifas, which represents the French aerospace industry.

France’s research ministry did not respond to a request for comment before Science|Business’s deadline.

AUKUS projects begin

As it mulls new partners, AUKUS is already starting to launch R&D projects. At the end of March, it launched a first in a series of innovation challenges, focused on electromagnetic warfare.

The US has earmarked $25 million in 2024 for AUKUS innovation activities, according to a report for the US Congress last year. There will be a push to get AUKUS defence innovation agencies to work more closely together.

Aside from joint innovation projects, the alliance is also cooperating across a range of technologies, including: cyber security; artificial intelligence; quantum positioning, navigation, and timing; underwater vehicles; hypersonic missiles and methods to counter them; electronic warfare; and deep space radar, according to an assessment by the UK parliament released last month.

In addition, there’s a drive to get AUKUS defence firms to work more closely together too. Last December, AUKUS defence ministers said they would create a industry forum, as well as a AUKUS Defense Investors Network to “strengthen financing and facilitate targeted industry connectivity”.

Enter Japan

Given the sensitivity of military technologies, bringing even close allies like Japan on board is fraught with difficulties.

This week’s announcement stops short of making Japan a full member of AUKUS’s pillar II, instead only saying that the alliance is “considering cooperation” with the country on certain projects.

The country still has highly restrictive arms trade conditions, and lacks the anti-espionage measures needed to be fully trusted with sensitive technology by AUKUS, according to an assessment by the Perth USAsia Centre, an Australian think tank.

For example, prison sentences for espionage – which only run up to 10 years – are much laxer than in AUKUS countries.

Still, Japan’s government spends about three times as much as Australia on defence technology, said Rena Sasaki, a researcher focusing on Japan’s military at Johns Hopkins University.

But it only spends half of the UK’s total, and all are dwarfed by the US, according to the most recent statistics from 2017.

To address research security issues, this week a bill to create a new security clearance system was approved by Japan’s House of Representatives, Sasaki said.

She downplayed the idea that AUKUS involvement would hinder work with the EU. “Japan has already concluded defence equipment and technology transfer agreements with France, Germany, and Italy,” she said. “Therefore, it is unlikely that AUKUS will make those partnerships more difficult”.

Japan is also working with Italy and the UK on an “innovative stealth fighter aircraft” under the so-called Global Combat Air Programme.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.