The review of the €75.6B eighth framework programme will feed into evidence to be published this year that will shape the future of EU research and innovation

The €75.6 billion Horizon 2020 framework research programme that ran from 2014 - 2020 had a huge impact on the European economy, its scientific output, and on society, but was short on budget, needed simplification and should have included better support for women researchers and entrepreneurs, a review shows.

The Horizon 2020 evaluation, carried out by the European Commission, is one of the first major documents that will inform the scope and aims of the next research programme, Framework Programme 10 (FP10), which will start in 2028.

Horizon 2020 helped fund over 35,000 projects around the world, but was €159 billion short of being able to fund all proposals judged to be “above the quality threshold” in each call. In addition, it lacked the support needed to make the most of the quality research it funded, and despite seeing the introduction of Widening measures, failed to close the research and innovation gap between Europe's top and bottom performers.

Some of the shortcomings in this final evaluation were also identified in the mid-way review, published in 2017. That led to improvements being put in place for the current programme, Horizon Europe.

Budget

The €159 billion underfunding meant 74% of all high quality proposals, around 100,000, were not backed by Horizon 2020.

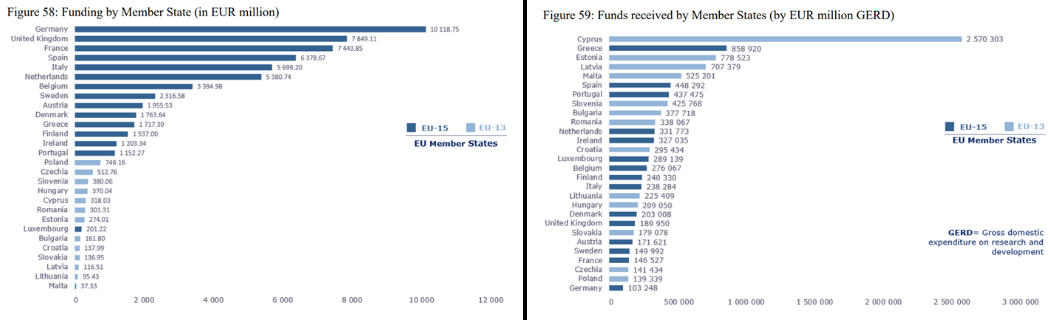

While the programme attracted around one million applications from 177 countries, around half of all funding went to organisations in just four countries – Germany, UK, France and Spain.

However, smaller countries such as Estonia, Greece, Cyprus and Latvia performed well when comparing how much funding they won against their gross domestic expenditure on R&D.

Every euro invested in the programme will bring around €5 in benefits to EU citizens by 2040 and add an average €15.9 billion to EU GDP annually, reaching around €429 billion from 2014 - 2040.

In comparison, the retrospective evaluation of FP7, which ran from 2007 – 2013, said each euro invested would yield €11 in return, while the programme was estimated as adding an extra €20 billion to the EU economy each year, or around €500 billion over a 25-year period.

The European Commission told Science|Business the difference is due to differing methodologies in the calculations, adding that "since FP7, the methodologies, macroeconomic models and underlying assumptions have improved..."

High impact

But in some respects Horizon 2020 outperformed FP7. Papers published by grantees were cited twice as often as the global average. In total, it generated 276,000 peer-reviewed publications, of which 3.9% rank in the top 1% of the most cited publications worldwide. This is a higher percentage than papers reporting research backed by other major international funders such as the US National Science Foundation.

The basic research was translated through to myriad scientific breakthroughs in fields including medical sciences, quantum mechanics, chemical engineering and composite materials. A quarter of all publications, the evaluation says, are linked to new research areas.

There was an overall boost to Europe’s research capacity, with Horizon 2020 supporting the mobility of nearly 50,000 researchers and giving over 24,000 researchers and organisations access to large-scale research infrastructures. The review claims this is likely to have led to many new projects and scientific research beyond the programme.

The public money drew in private funding and for every euro spent by the EU, the private sector invested 57 cents. In parts of the programme, such as public-private partnerships, companies paid in as much as three euros for every euro spent by the EU.

A much touted route to improving Europe’s innovation performance is creating better synergies with other EU and national funds. Programmes such as EU cohesion funds could support the take up and commercialisation of research results, but the Commission is yet to find a way to facilitate the flow of projects between different funds. That is another item for the to-do list.

(Slowly) delivering on policy

Framework programmes are increasingly becoming policy vehicles for the EU, and Horizon 2020 showed it can deliver. Climate action and health were especially big focus areas.

As the climate crisis escalates, Horizon 2020 helped scientists understand it better. A tenth of publications cited by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change come from Horizon 2020 and FP7 funded projects.

The programme also made headway in turning knowledge into innovation and delivering green tech, including advancements in hydrogen fuels and clean aviation.

But it didn’t put as much money into climate-related R&I as expected. The final number was 32%, just below the promised 35% of its €75.6 billion investment. Learning from this, the Commission is likely to push for better project alignment to ensure Horizon Europe reaches the 35% target.

Health was another big topic for Horizon 2020. The programme rapidly responded to Ebola and Zika epidemics, and in its last year, showed even greater speed and flexibility when the COVID-19 pandemic broke out, setting up dedicated calls and initiatives as part of a €1 billion pledge for coronavirus research.

Horizon 2020 also fed into long-term health priorities, in particular supporting projects that gave a deeper understanding of rare diseases and therapies and contributing to personalised medicine.

But the real-world impact of these achievements is hard to measure. Research can take years to deliver societal impact, making it difficult to measure progress. Plus, the review found Horizon 2020 impact monitoring used weak indicators and was too narrow in scope. This is another shortcoming the Commission hopes to remedy in Horizon Europe.

Simplification

The evaluation highlights the need for the programme to be further simplified, and this still applies today. Recently, The European Commissioner for research and innovation, Iliana Ivanova, said that there will be further simplification across all three pillars of the current Horizon Europe programme in the coming years.

Horizon 2020 did improve on its predecessor in this respect. The average time to go from submitting a grant application to an award fell from 313 days in FP7 to 187 days during Horizon 2020. Measures such as the use of electronic signatures and an annotated model grant agreement were cited as helping here.

Horizon 2020 also saw a pilot test of lump-sum funding, an alternative to cost reporting in which a project is given an up-front budget based on an estimation of its costs. Lump-sum funding is being more widely deployed under Horizon Europe and the report supports that move.

But speeding up grant application processes comes with its risks. The evaluation found that the error rate in expenditure reporting during projects was still too high and warned that “further tightening the time-to-grant target might not be necessary as it could inadvertently increase financial error risks”.

Could do better

Two areas highlighted as in need of improvement are the gender balance and the efforts to close Europe’s east-west research and innovation gap.

The number of women on proposal evaluation panels was 42%, above the 40% target, but women accounted for 43% of those on scientific advisory panels, below the 50% target. The number of female researchers participating in projects was just 23%.

Horizon 2020 was the first framework programme to include Widening measures designed to help countries lagging behind on research and innovation performance. The report found 28% of the highly cited publications produced by institutions in Widening countries could be linked back to Widening measures. Stakeholders widely praised the tools such as Twinning, Teaming and ERA Chairs as being beneficial.

But Widening countries only won 8% of the total EU contribution, just a slight increase from FP7. Institutions from these countries represented 12.3% of Horizon 2020 participants, up 1.3% from FP7.

Around half of the initial €816 million set aside for Widening measures went to institutions in just four countries, Portugal, Cyprus, Poland and Estonia.

Commissioner Ivanova noted recently that the issues for Widening countries highlighted in the report, such as limited capacity to manage international research and innovation projects, brain drain, weak national support systems and a lack of easily available funding alternatives, “still persist”.

One positive was Horizon 2020’s push for greater open access to research papers, which became a general requirement under the programme. The evaluation found that 82% of publications were freely available online.

Editor's note: This article was updated 31 January to include clarification from the European Commission.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.

A unique international forum for public research organisations and companies to connect their external engagement with strategic interests around their R&D system.